© Iwan Baan

It’s 1995. The Swiss architect duo Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron have won the competition to turn the disaffected power station designed by Giles Gilbert Scott into a great museum of modern and contemporary art for London. No one could have anticipated the success of what would become one of the greatest global institutions: The Tate Modern. Cynics ridiculed the goal of 1.8 million visitors a year. In the first year of its opening in 2000 there were 4.7 million. Today more than 5 million visit it annually. In 2000 Herzog and de Meuron were awarded the prestigious Pritzker Prize, the architect’s Nobel.

A CATHEDRAL FOR ART

The extension of the museum opened to the public on June 17th was also conceived by the famous Basel duo’s agency. Since the Tate Modern, Herzog & de Meuron have multiplied their museum projects and become nothing short of an international reference. The San Francisco De Young Museum, the extension of the Unterlinden Museum in Colmar, the Pérez Art Museum in Miami, the extension of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the Schaulager in Basel, the Blau Museum in Barcelona… In other words their comeback on the banks of the River Thames has been hotly anticipated. And is anyone disappointed?

“This building that was once upon a time the beating heart of London is today its cultural cathedral.” – Lord Browne, Chairman of the Tate

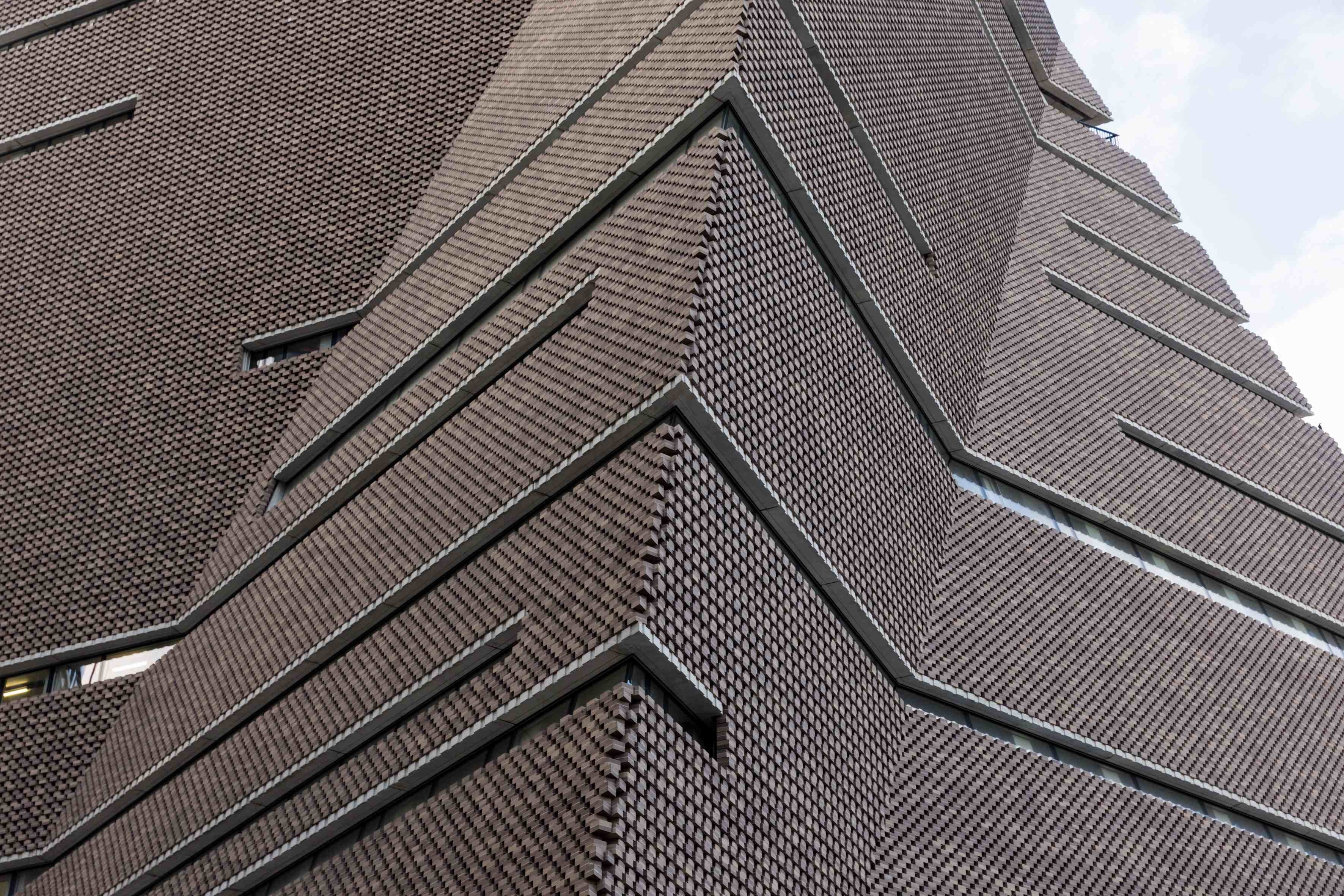

Not if we listen to the Tate chairman, Lord Browne. “This building that used to be the beating heart of London is today its cultural cathedral,” he enthusiastically announced before a crowd of guests at last Tuesday’s official opening. But the 64.5m tall tower with its 10 storeys doesn’t only have fans. “Too depressing!” Some say of its façade and choice of bricks – 336,000 for its openwork façade anchoring the building in an industrial past. “A veritable bunker!” A reference to its compact structure and deliberate choice to abandon the large glass entrances, an easy symbols of modernity for so many contemporary edifices. And yet what a success!

THE NEW TATE MODERN, BETWEEN STAR WARS AND BLADE RUNNER

Far from being a compacted bunker, the new wing is more like the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Its majesty evokes spiritual and religious monuments. Reaching into the sky, the building recalls the Tower of Babel, embodying a human culture determined to confront the gods. Or maybe a new Inca or Greek temple. It’s certainly an edifice to the glory of Art, the new contemporary idol. But these backward looking references don’t truly do this one-of-a-kind architectural object justice. A crooked object that seems to be in perpetual motion as if under the impetus of high-tech electronic mechanics transforming its appearance like a Rubik’s Cube. The imagination convened on this site is pure science fiction. The new Tate Modern is a spaceship from the Star Wars Empire. Better than that, a building straight out Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner.

La nuit tombée, la lumière intérieure s’échappant des percées de la façade ne fait qu’accentuer l’impression de faire face à un croiseur galactique. Pour Jacques Herzog : “La forme extérieure du bâtiment paraît aussi mystérieuse que déroutante, mais elle résulte pourtant d’une interprétation géométrique très rationnelle des rues environnantes et du quartier. Les volumes qui en découlent nous rappellent une pyramide, mais aussi une tente. Les interprétations sont ouvertes.”

A CONSISTENT CHOICE: TWO WINGS FOR ONE BUILDING

“Our goal was to conceive a new building that fits in perfectly with the existing one,” continues Jacques Herzog. “We wanted to create a single entity where you cannot distinguish phase 1 from phase 2.” For this the choice of brick was primordial in order for the architects to create a sense of continuity in the façade of the two wings. “The brick coating can be read in two ways. Solid and traditional, it blends in with the existing bricks of the power station [that form the original Tate Modern]. And yet it appears particularly light, almost like a textile or a knit, especially on the inclined parts.” A bridge overlooking the gigantic hall works on linking the interior, the wing originally known as the “Boiler House” to the new wing called “Switch House”.

“The brick facade is perforated in such a way that the sun can enter and soften the strength of the concrete.” – Jacques Herzog

ART IN THE MIDST OF FUEL TANKS

Another daring choice of duo is the erection of the new wing on the existing fuel tanks – the very ones that were used to power the turbines of the Tate’s monumental hall. These tanks, spaces of 30m installed in the basement, remind us of the industrial origins of the building. But now their concrete architecture is welcoming a fantastic line-up of performances and films, from the dreamy videos by Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul (Palme d’or in Cannes) to the eccentric instruments of Tarek Atoui.

60% MORE SPACE… not necessarily devoted to art

While the new wing allows the museum to increase its floor space by 60%, this gain is only partially set aside for exhibition space. Only levels 2 to 4 will be hosting the three inaugural exhibitions. The first - and most exciting - entitled “Between Object & Architecture” (level 2) looks at the relationship between the work of art and its surrounding environment. Donald Judd, Rachel Whiteread, Daniel Buren, Cristina Iglesias, Eva Hesse, Rasheed Araeen, Bruce Nauman and Ricardo Basbaum have all been summoned. On level 3, “Performer and Participant” closely scrutinises the links between art, performance and choreography, while level 4 gives over an impressive space to Louise Bourgeois and a space that’s much too small to the urban theme of “Living Cities”. The rest of the space is sucked up into a bar and boutique on level 1, with eight gigantic elevators on every floor, staircases and toilets everywhere, and a restaurant on level 9.

AN ARCHITECTURAL PROMENADE BETWEEN WOOD AND CONCRETE

This new wing in brut concrete and pale oak wood provides vast and open volumes that are particularly interesting on level 2. It’s interestingly different from one floor to the next. “The brick façade is perforated in such a way that the sun can enter and soften the strength of the concrete,” comments Jacques Herzog. “The biggest difference with the old building is the flux management. Within the new wing the public will have access to a wide selection of stairs and railings that create a sort of architectural promenade with benches and alcoves where you can stop and chat.”

800 WORKS BY 300 ARTISTS FROM 50 DIFFERENT COUNTRIES

The other major revolution at the new Tate Modern – and we’ll be going back to this in more detail soon – is obviously the new installation in the heart of the two wings. “Now we’re able to tell a more international, more diverse and more stimulating history of art,” explains Nicolas Serota, director of the Tate. “We wanted to trace the history of living arts, from cinema to new media, and above all acquire and show more work by women artists.”

The end of the Western, white male artist hegemony... The new installation is resolutely more interesting, more feminine and more diverse in its choice of media. Performance takes pride of place. Video is also very present. Of the 800 works, 75% of them have been acquired since 2000. The 300 artists on show come from 50 different countries including Chili, India, Russia, Sudan, Lebanon and Thailand… It’s an undeniable success. And let’s not forget the Tate Modern’s iconic masterpieces – the Richter, Rothko and Riley rooms cannot help but move you to tears.

On the top floor of this new wing, at more than 60 meters high, the visitor can contemplate 360° of a constantly changing London, – the cranes are countless – its most beautiful buildings (from Saint Paul’s Cathedral to Renzo Piano’s Shard) and its stormy sky. An exhilarating view offered by the Tate Modern that perfectly symbolises its architectural and artistic ambition: to stay at the top.

www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-modern