In Paris, Theaster Gates is exploring the history of migration and slavery; at the 2019 Venice Biennale, the sculptor Martin Puryear is representing the U.S.; at London’s Tate Modern, Kara Walker will be showing in the Turbine Hall in October. We’ve come a long way from the time when very few African-American artists managed to get themselves heard. In 1970, Melvin Edwards was the first to have a solo show at the Whitney, but his example was not repeated. Decades later, David Hammons made a name for himself among international collectors, François Pinault in particular. “In the 1960s and 70s, even the most politicized African-American artists were recognized without having to belong to a group or a minority, each pursuing an independent career,” says gallerist Nathalie Obadia, who represents Mickalene Thomas and Lorna Simpson.

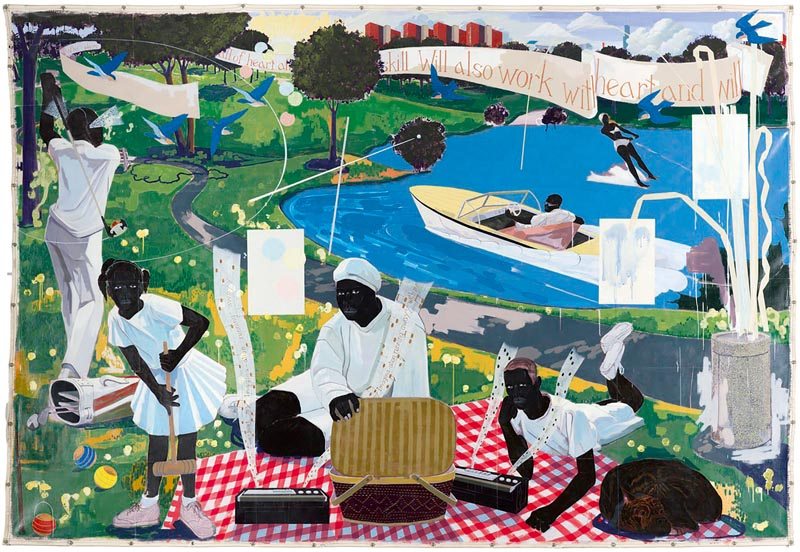

In 2018, a work by Kerry James Marshall was auctioned for $21.1 million – four times his previous record.

The year 1997 marked a turning point when Robert Colescott represented the U.S. at the Venice Biennale and Kerry James Marshall was invited to Documenta in Kassel. In 2016, Paul Gardullo, curator at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., told The New York Times, “American history is profoundly African-American... You can’t understand America without black America. You can’t understand our struggle for equality. You can’t understand jazz or rock and roll.” According to the website Artnet (September 2018), the number of exhibitions devoted to black American artists grew by 66% between 2016 and 2018. Institutionally fuelled by shows like Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power at Tate Modern (2018), Outliers and American Vanguard Art at the National Gallery in Washington and Sam Gilliam, The Music of Color at the Kunstmuseum Basel (both 2018), this shift has also impacted the market, though not necessarily where museum acquisitions are concerned: Artnet’s figures reveal that African-American artists accounted for under 3% of American museums’ purchases since 2008. But where private collectors are concerned, it’s a whole other story. Don and Mera Rubell got the ball rolling in 2009 when they showed 30 African-American artists at their Miami collection.

Just under a decade later, in 2018, a work by Kerry James Marshall was auctioned for $21.1 million – four times his previous record. The piece had previously been acquired, in 1997, by Chicago’s Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority for just $25,000, and only five short years ago Marshall’s works were selling for around $300,000. For Johanna Flaum, a specialist at Christie’s, the game changed in 2016 with his exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, which afterwards travelled to New York’s Met and L.A.’s MOCA. Powerful New York dealer David Zwirner then added Marshall to his stable, and today they are at nos. 1 and 2 respectively in ArtReview’s November 2018 “Power 100” list.

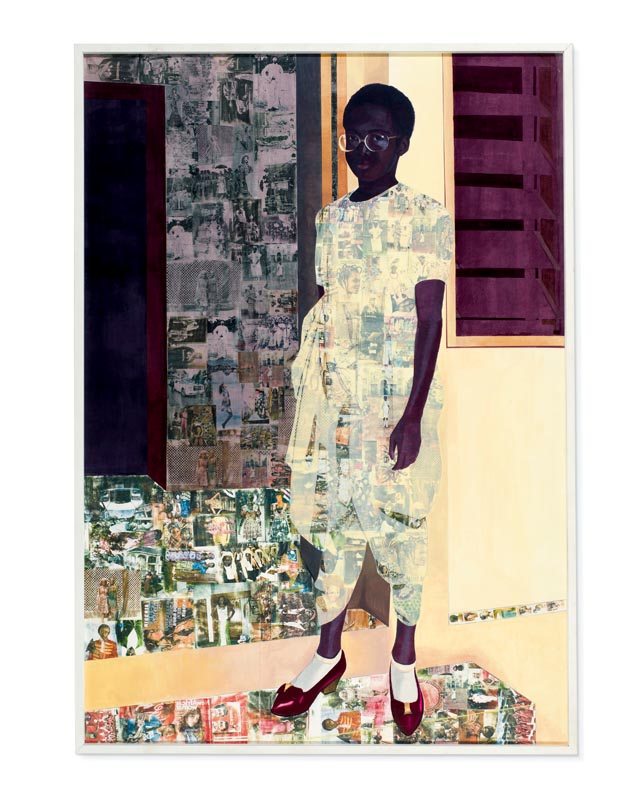

Theaster Gates has also seen his prices climb. While in 2013 Chicago dealer Kavi Gupta was selling his works for €50–75,000, you’d now need to shell out around €350,000. Discovered in 2001 at the Studio Museum in Harlem’s Freestyle show, Mark Bradford’s work has also gone up: in 2003, it was selling for around €18,000 a piece at Anne de Villepoix’s Parisian gallery, but since Bradford’s participation in the 2017 Venice Biennale his prices have quintupled. The vogue for African-American artists has also benefited African artists in the U.S., such as Nigerian-born Njideka Akunyili Crosby, whose prices have risen 16-fold in just six years – and this is no doubt only the beginning, since she’ll be appearing at this year’s Venice Biennale.