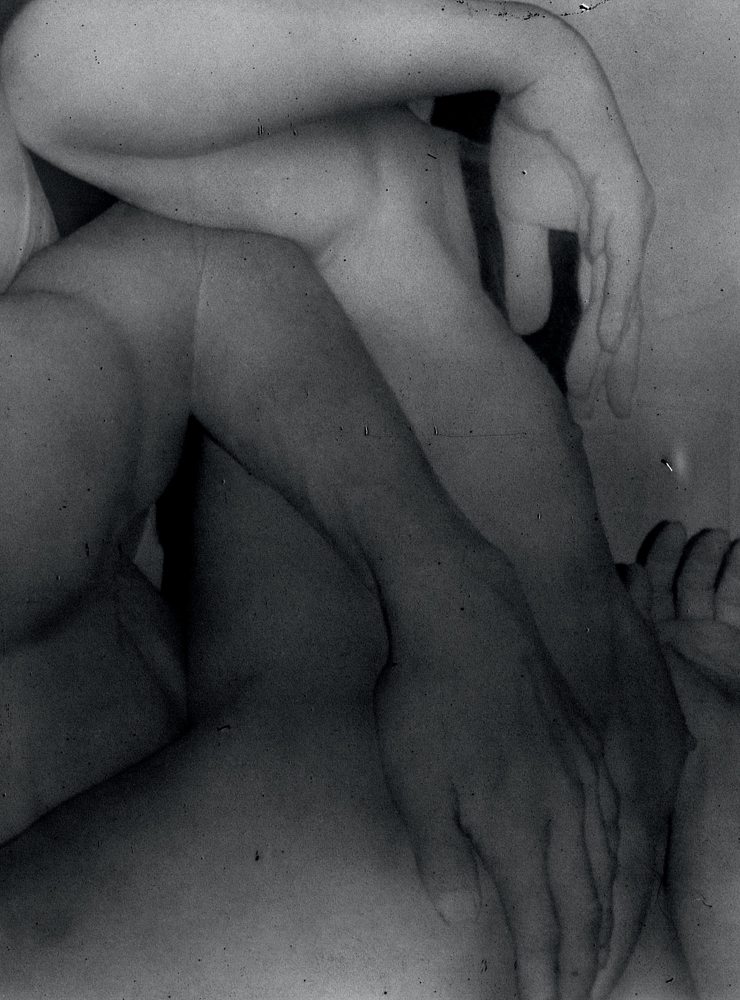

Daisuke Yokota, who started out in music before turning to visual art, has been developing a unique aesthetic of layers, strata and superimpositions for a decade now. He often invokes sound, referring to the composer Aphex Twin: what would be the equivalent of sound reverberation in a photograph? How can time be included in a still image? In 2015, under the title Inversion, he made a large set of solarized photographs using the recto-verso superimposition of pages from artists’ books which he printed on translucent paper (Matter Waxed, 2014–15) – a superimposition of often figurative images that engendered a seemingly abstract result, like our own intertwined memories that arise in the present and confuse our reading of the past.

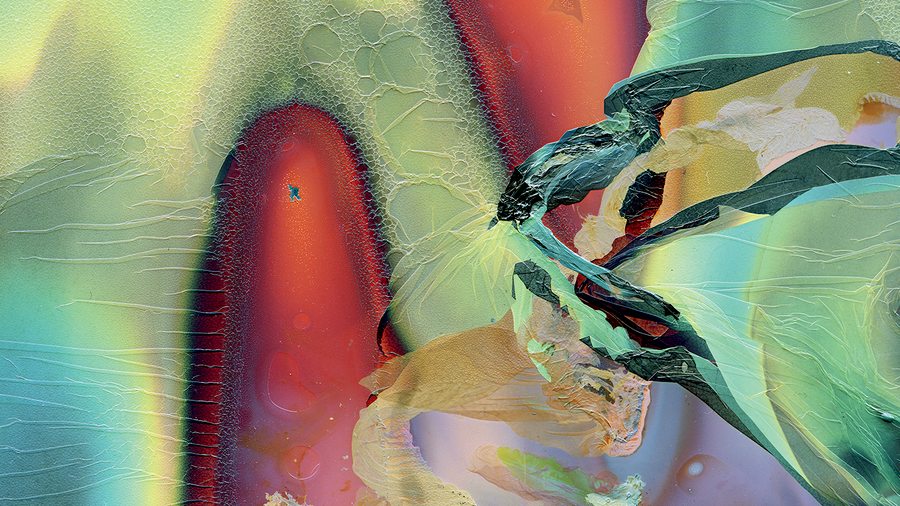

While Yokota’s early works, such as Back Yard (2012), Site/ Cloud (2013) and Corpus (2014), still contained figurative images – bodies, landscapes, architecture –, he started to break the association between the medium or the photographic material and the retranscribed image, refusing the principle of the photographic index. The series Color Photographs (2015), Matter (2016), Scum (2018), Dregs (2018) and Sediment (2019), right up to Untitled (2020), are like stages in a journey through technical variations on the same theme of photography distilled to its matter, to what it is and not what it represents. The most recent, Untitled, is significant in this respect: the object no longer refers to anything and doesn’t even need a title, as though identification with the world had been definitively exhausted.

In 2016, Yokota created Mortuary, which comprises gigantic rolls of developed and fixed photosensitive paper that showed only the trace of the chemistry used, accompanied by a soundtrack of muffled vibrations. Nonetheless, this immersive installation referred to a real-life event: as a child, Yokota suffered from feverish attacks that caused intense hallucinations, and Mortuary evoked this buried memory. Abstraction has a function in Yokota’s work: “A photograph without the intervention of human perception is just a material, but when a human being sees it and thinks about it at a certain time and place, the photograph becomes an interesting phenomenon. To think about photography is to think about the human being him- or herself.”

In preparation for Room. Pt. 1, which was shown in spring 2016 at the Guardian Garden space in Tokyo, Yokota isolated himself for two months in various love hotels in Tachikawa, near his home in the Tokyo Prefecture – as if he were running away from his own house. Though he had been using travel as a professional context for a decade, he had never before “travelled” through his own city. During the two months of Room. Pt. 1, he strove to maintain a traveller’s sense of distance and experienced his hotel rooms as temporal capsules where time, suspended and suddenly insignificant, is conducive to the emergence of memory and the elsewhere. “When you go to a love hotel alone,” he explains, “you don’t need to think about what’s going to happen next, because your goal is to ‘just be there, and when your time is up, you can just leave. When you are in such a meaningless moment, unexpected memories are sometimes evoked, as if you were dreaming, and although you are conscious, you seem to be somewhere else.”

These hotel rooms are comparable to caves into which the outside world invites itself by surprise. “In a cave, the image of light coming through a hole into the dark space is like a hallucination, isn’t it? The image that is projected there is of the outside world, but it is not the outside itself. The viewer only imagines the outside world from there. For me, the act of being in one place and fantasizing about others is very photographic. In this sense, I see the love hotel as a modern-day cave, and the space itself overlaps with the metaphor of the camera obscura.” In Room. Pt. 1, Yokota piled up photographs, videos and sculptures, the superimposition of layers of images evoking the way in which the past invites itself into the present, when one moment evokes another, when one place summons up another.

There is a parallel in Yokota’s need to withdraw from the world for two months, to remove himself from the contingencies of everyday life, and his refusal of the power of identification with the world often granted to photography. “Basically, I think it doesn’t matter where the light is pro- jected, and I think it doesn’t matter what is there, even if there are people, as long as there is a place where the light can adhere.” Yokota lives in Tokyo, but ultimately that doesn’t matter. By removing himself from the world, he is at home everywhere. This is how he sees light – a lesson for photography, and for all of us who have lived in isolation over so many recent months.