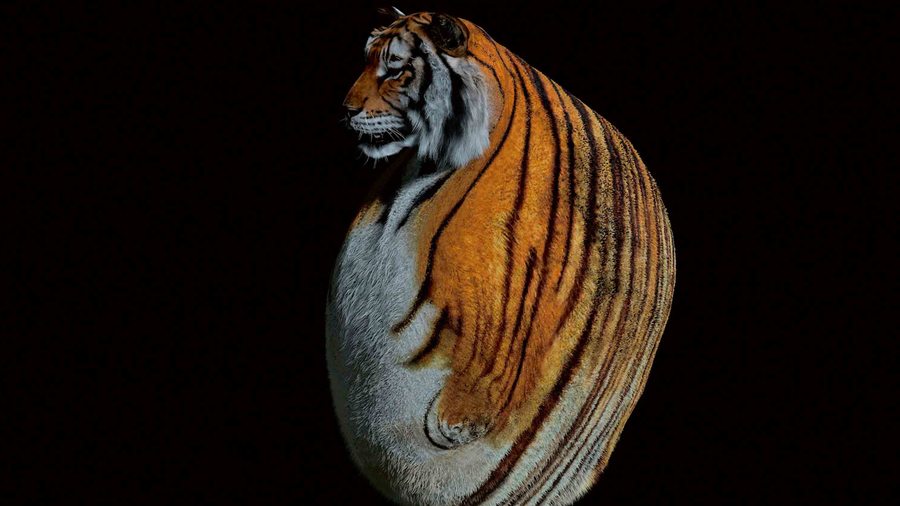

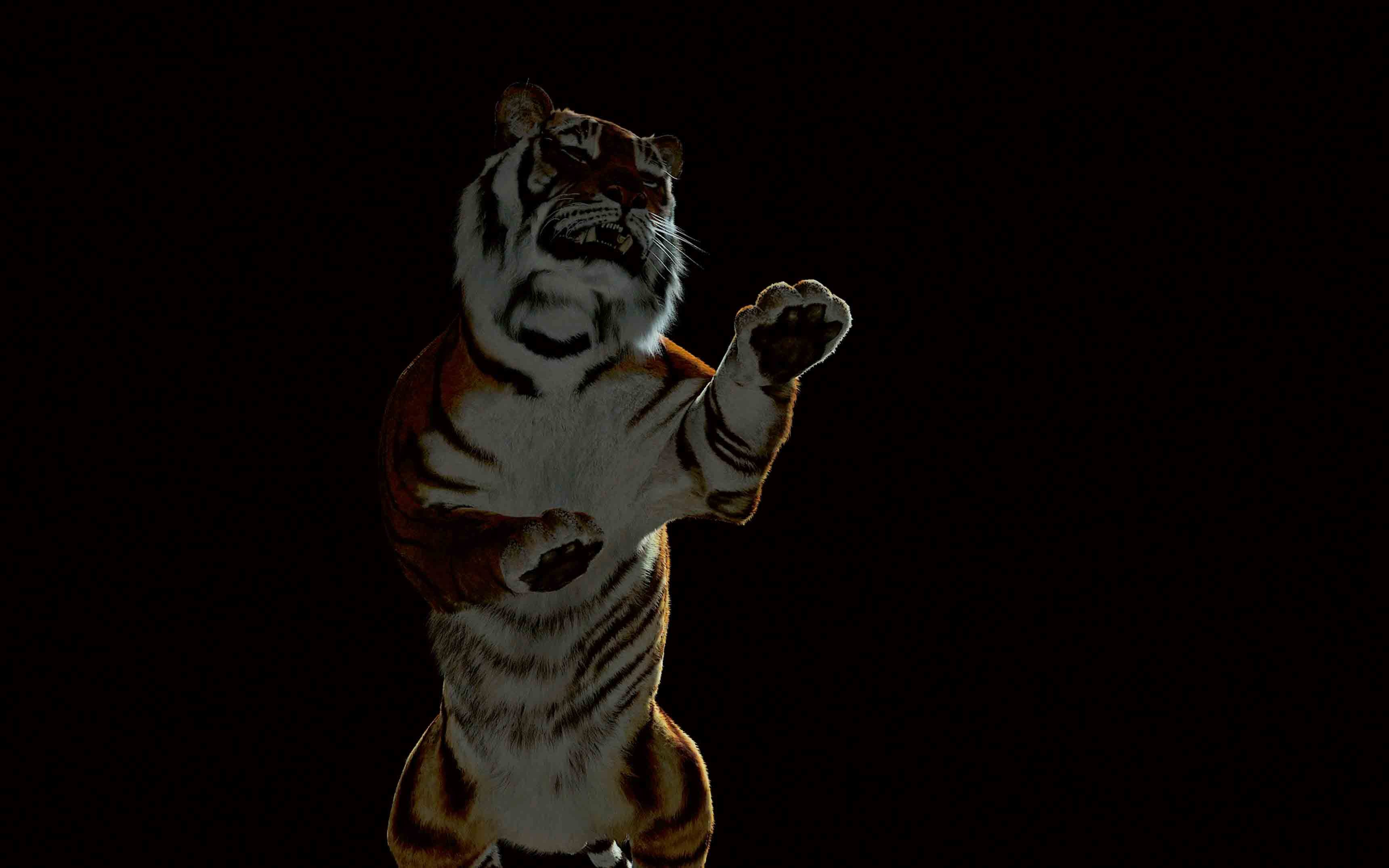

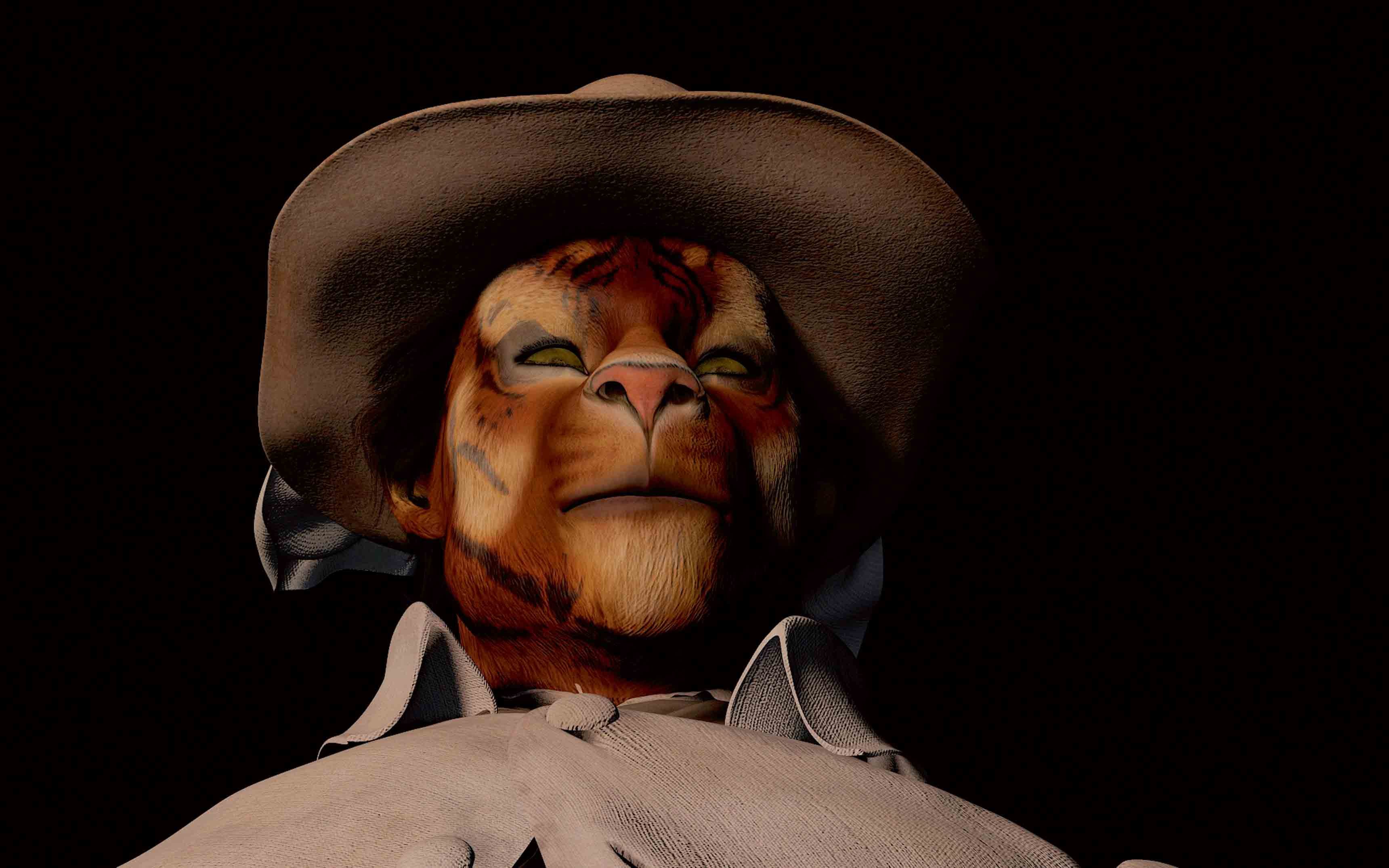

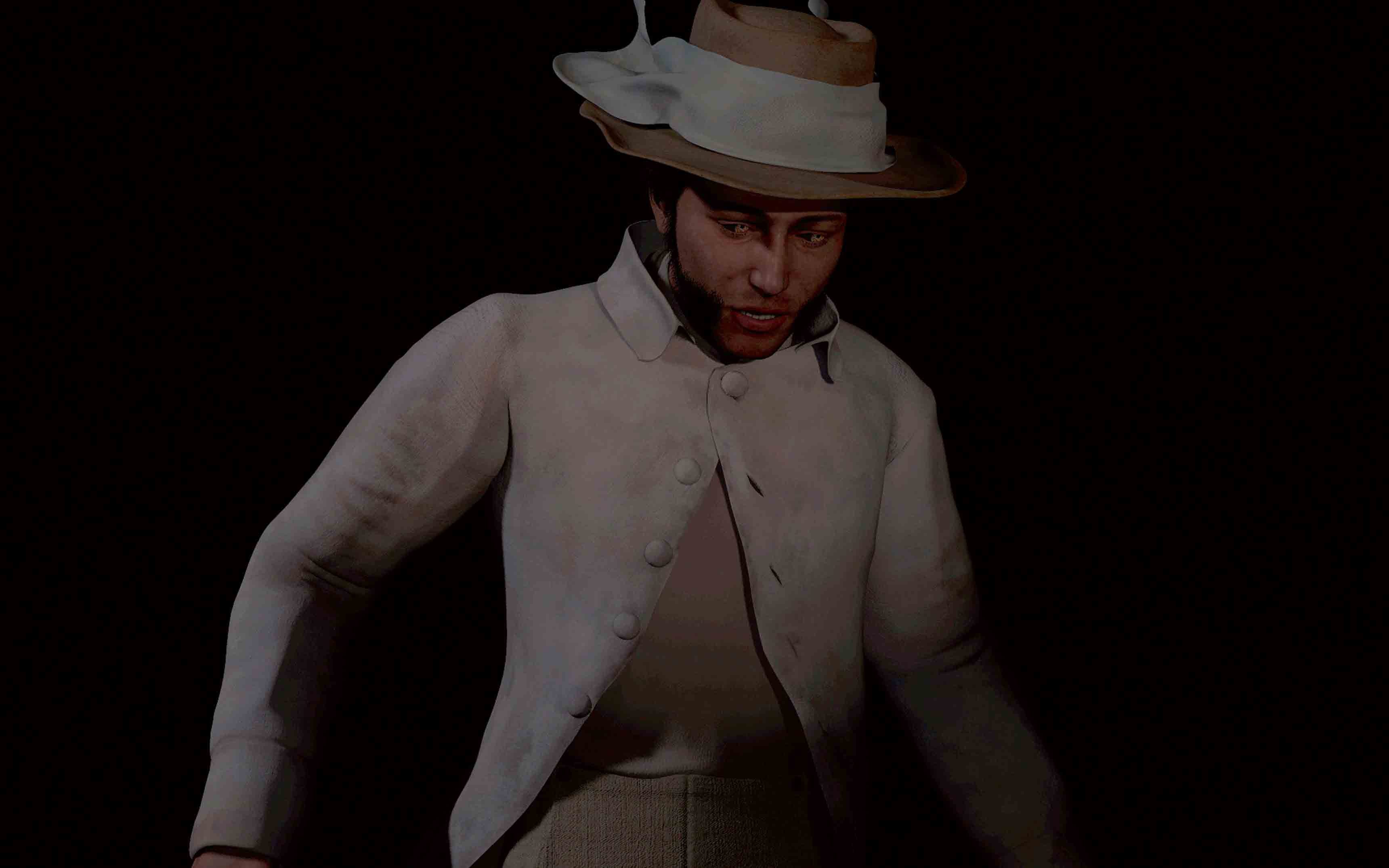

It’s 1835, and Superintendent George Drumgoole Coleman is navigating the Malaysian forest with the help of his theodolite – a topographical instrument that can measure angles and was a key cartographic tool in the control of territory by colonizers. Suddenly, a tiger pounces from out of nowhere. It was the first (known) encounter between a white man and a Malaysian tiger. The scene, reinterpreted in a 3D animation by artist Ho Tzu Nyen (born in 1976 in Singapore), has given birth to a video installation that takes the form of a mystical experience. On one side of the room, on a giant screen, there’s Coleman, the white man – colonization in person, imposing his vision of a rationalized, measured, classified world. Opposite him, on the other screen, is a man-tiger, the mythical southern-Asian creature who is at once god, ancestor and protector. The beast is both a human being who can become a tiger and a tiger who can become a human being and live among the village folk. As such he represents the blurring of identities, their constant evolution, which prevents any definite classification. To the very Western question of “How many tigers are there in the forest?” it is said that the locals still enjoy replying, “Five or six.” For everything depends on the current state of the man-tiger, whether man or tiger or both... The creature thus becomes the symbol of a lack of opposition between nature and culture in Asia, an opposition which is an inherent and fundamental notion in Western thought.

With 300 invited artists and a dozen exhibitions, the Dhaka Art Summit succeeds in one of the major challenges of our times : promoting an art taht is decolonized of Western thought systems that claim to be universal.

It’s February 2018 in the heart of Bangladesh, and Ho Tzu Nyen’s installation is one of the highlights at the Dhaka Art Summit. Every two years, the capital of this country with its very limited infrastructure nonetheless manages to put on a serious rival to the big Western art events. Initiated in 2012 by the collectors Nadia and Rajeeb Samdani and orchestrated by curator Diana Campbell Betancourt, the Summit takes the pulse of a regional production that is still overlooked by the West. With 300 invited artists and a dozen exhibitions, it especially succeeds in one of the major challenges of our times: promoting an art that is “decolonized” of Western norms and thought systems that claim to be universal, deconstructing all the clichés and values we take for granted.

But in Dhaka it’s not just about relations with the West, for the art there responds above all to a local imperative, that of expressing – through painting, photography or sculpture – terrible events and situations: ecological dramas, political or economic refugees, the hundreds of thousands of Rohingyas fleeing persecution in Burma... The imperative, above all, to record and transmit a History or histories that censorship or war combine to efface. An imposing figure in wood holds in its arms another body, as a mother holds her son who is prey to fear and fright; it’s a work by the father of modern Pakistani sculpture, Shahid Sajjad, who takes such dramas as his subject in a series entitled Hostages. Making visible the invisible is after all what artists have long tried to do... Sajjad, but also Minam Pang, Munem Wasif and Nilima Sheikh stand out in Dhaka as true poets of civilizations, peoples and minorities. By adopting local traditions and practices, they express these tragedies without being literal or illustrative (most of the time at any rate).

Defined by the anthropologist Jason Cons as “sensitive spaces,” the conflict zones portrayed and evoked in Dhaka are in fact the places where the world’s great movements clash: nationalism and globalization, migration and minority rights... As such they are the crucible of our contemporary chaos, and consequently the Dhaka Art Summit could not fail to address the massive phenomenon of economic migrants. Over 10 million Bangladeshis work abroad, many of them recruited by the construction industry, from Dubai to Singapore. In Dhaka, the portraits of migrants painted by Liu Xiaodong give back their humanity to these enslaved men by offering them a face, a singular image that is the antithesis of that which usually accompanies them, the standardized passport portrait which reminds them at each moment of their (sub) status as (non) citizens. And yet it’s these men who build the contemporary globalized world and the cityscapes of the future, installing communication cables under the sea, replying to questions from all over the globe 24 hours a day in delocalized call centres. In his video Sea State 6 (2015), Charles Lim filmed Bangladeshi workers in underground hydrocarbon stores in Singapore. Individuals appear like tiny ants inside these monumental caverns, which symbolize both the economic system (overwhelming and trapping the migrants) and their territorial and social status (denied all visibility). We can only be thankful that, in response to these “sensitive spaces,” we still have the contemplative, sensitive space that is art.