Collective action, community organising, family support: such nurturing, mutual enterprises fall within the broad arena of what we call social work. This is a field of actions and behaviours that suggest a tendency to caregiving and communality, and with them an implicit refusal of profit and exploitation. Such selfless traits are rarely associated with the art world at its pointier end, but away from the market they form the basis of cooperative, supportive communities that in turn provide environments that allow for free expression and creative risk taking. As a corrective to market forces, social work allows art to stay fresh.

For its last few editions, Frieze London has created a very visible platform for such virtuous practice. Nestled among the blue chip gallery booths, the über fair has dedicated subsectors to art from previous decades made with little concern for – or indeed outright rejection of – institutional mores. In 2016, a curated section on the 1990s explored that decade’s artist innovators and the galleries that supported them. Last year’s Sex Work section, curated by Alison Gingeras, celebrated female artists of the 1960s and 70s whose fearless exploration of subjects sexual had seen their work censored, reviled and blocked from exhibition.

Under the title Social Work, a group of ten female critics and curators this year pays tribute to women artists whose work during the 1980s created broader support structures for those around them. Working with artist-run organisations and cooperatives, they offered new models beyond the male-dominated institutional mainstream, and addressed issues of representation and unpaid women’s labour. Among those featured are artists whose contribution to the culture of that decade has gone largely unheralded, as well as figures – such as the Royal Academician Sonia Boyce – who have gone on to wider recognition.

Curators Lydia Yee, Fatoş Üstek and Melanie Keen discuss three of the artists featured in Social Work, and suggest why it is important to re-assess their legacy three decades later, in an era when work by women is still under-represented in the world’s museums, and undervalued by the market.

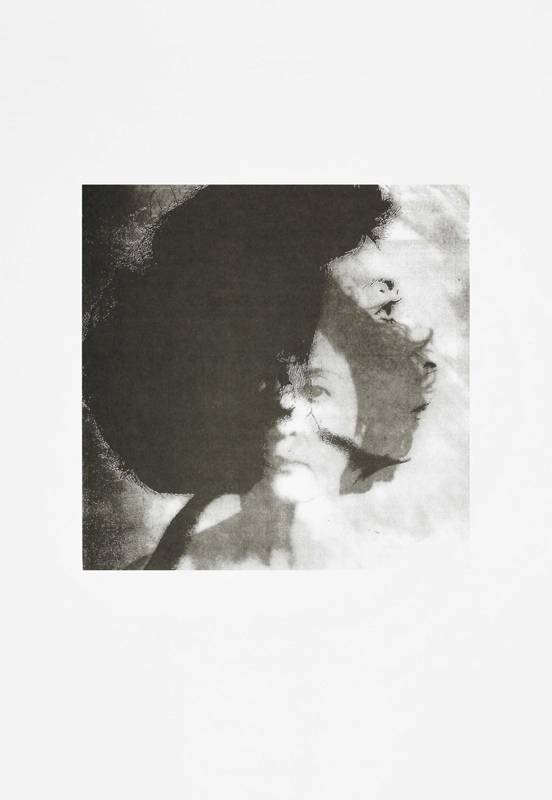

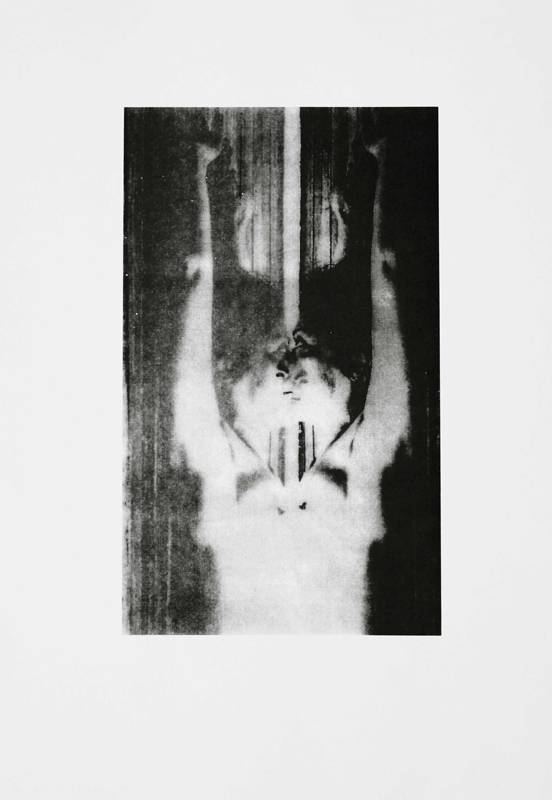

“Manuscript”, Ipek Duben, 2011.

“Manuscript”, Ipek Duben, 2011.

Fatoş Üstek on Ipek Duben

“Ipek Duben’s work has a strong political rigour,” says curator Fatoş Üstek. “She is a senior artist who has been actively working across continents, concentrating on issues of identity, representation and migration.” Born in Istanbul in 1941, Duben studied art at the New York Studio School before returning to Turkey to pursue doctoral studies in Art History. Since completing her PhD, Duben has worked as both artist and critic, producing an extensive body of essays on art and ideas, alongside her installations, sculpture, painting, video and artists’ books.

Üstek suggests that Duben’s specific interest in the human impact of political turmoil, as well as the position of women in society, make her work particularly relevant for the present moment, with Turkey feeling the pressure both of an authoritarian political regime and the mass migration caused by years of brutal conflict in Syria. “Her body of work on migrant subjects – manifested in video installations, as sculptures and drawings – has been crucial to consider during our selection process,” says Üstek. “Her quest in the human flow across borders is timely and piercing.”

Melanie Keen on Sonia Boyce

Curator Melanie Keen admits that her relationship with Sonia Boyce’s work is both “personal and institutional.” Experiencing the artist’s chalk and colour pastel drawings in the 1980s “was quite powerful,” recalls Keen: “I hadn’t seen black people represented in art in the way she was showing them – and black women in particular.” Keen was first introduced to Boyce’s work by a tutor on her foundation course: the recently graduated artist became “a bit of an informal mentor to her” – reflecting the need for coalition felt by Britain’s black art students in the 1980s.

In 2016, Boyce became the first black woman to be nominated into Britain’s Royal Academy, a 250-year-old artist-run organisation that self-selects the country’s art elite. Born in 1956, Boyce has spent much of her career indicating the forces that have, for so long, kept people of colour and women out of such institutions, questioning who gets to choose the art seen and owned by the British public and why.

While Boyce is now a leading figure in the British art world, Keen wants to remind a new generation about the pioneering work of artists associated with the British Black Arts Movements in the 1980s – among them, too, Keith Piper, Claudette Johnson, and Lubaina Himid: “They brokered these really important discussions about what it means to be present in institutions or not.”

Lydia Yee on Nancy Spero

A founding member A.I.R. (Artists in Residence, Inc.) – America’s first not for profit gallery for women artists, which opened in Brooklyn in 1972 – Nancy Spero was, nevertheless says Lydia Yee “an artist who really came to prominence in a wider community in the 1980s.”

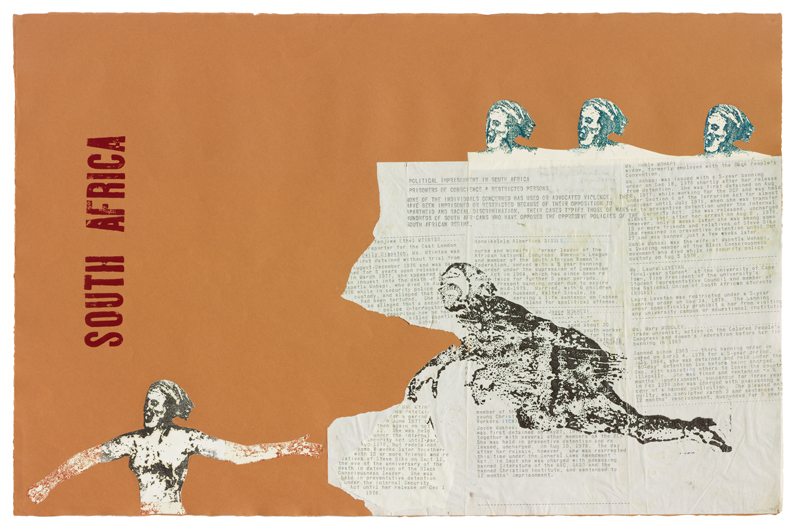

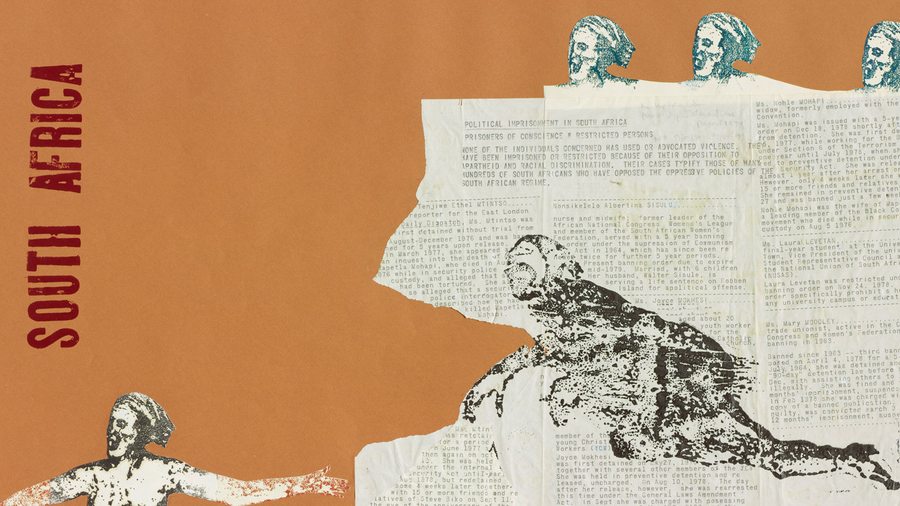

Working at first with oil paint, then increasingly with collage and printmaking, Spero sought out representations of womanhood from across ages and cultures. Following her War Series, made in the late 1960s and early 70s, violence in conflict – and in particular violence toward women – became abiding themes. “A lot of political art in recent years has been more directly representational, using photography and video,” says Yee. “I think Spero shows there’s another way to make political work that is representational, but works with the imagination and draws on many aesthetics.”

The takeaway vision of New York’s art world in the 1980s is a heated marketplace dominated by ballsy masculinity expressing itself at scale; Jean Michel Basquait, Jeff Koons, Julian Schnabel; as well as the cool of the ‘pictures generation’. Spero stood apart. “While she registered the masculine dominance of oil painting she did continue to paint and work with the figure,” says Yee. Her work gave “the younger generation licence to work with collage, to work by hand and to work with a much more personal repertoire of images.”