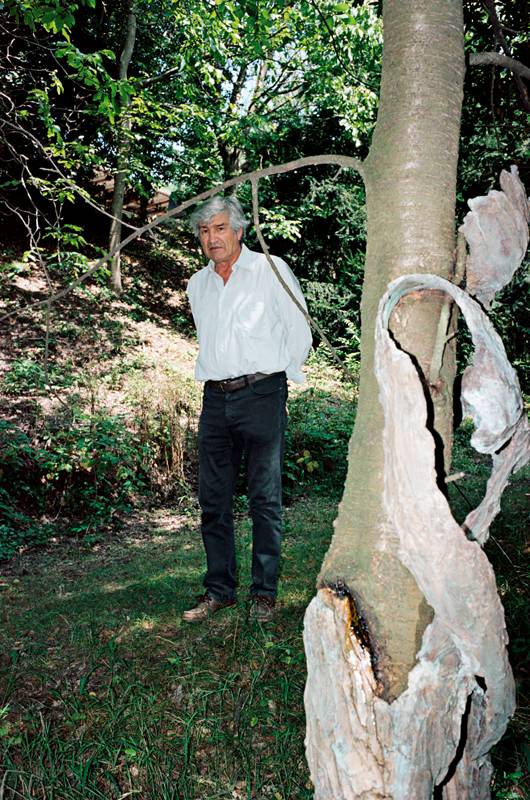

In the shade of a wild apple tree, on his estate in the mountains outside Turin, Giuseppe Penone prepares his work. A white cloth is spread out over a 10 m-long stone table. The artist carefully collects a few branches and leaves, rubbing them vigorously first on his hand – drawing inspiration from their scent – and then on the sheet, which becomes spattered with the vitality of chlorophyll. The verdant traces seem to fertilize the fabric, generating abstract figures, vines that turn gradually into trees. It’s a forest, just like the 16 ha of greenery surrounding his villa. But Penone does not seek to imitate the image of nature, but rather to reveal its vital processes. Chlorophyll irrigates the cloth in the same way it irrigates the branches of the tree to help it reach up towards the light of the sky.

“A tree fixes in its structure every second of its existence”, he explained on the occasion of a 2013 exhibition at the Château de Versailles. “The form of its development corresponds to a vital necessity. In a tree, there isn’t a single useless branch. That means the tree is a perfect sculpture”. In a seminal 1968 work, Penone’s hand, moulded in steel, grasps the trunk of a young tree. The tree’s slow growth is marked by this presence, the trunk enveloping the hand and growing around it. “I used my body like a tool”, smiles the now 72-year-old. A tool that works to reunite animal and plant life, a tool of animist thought for which the universe forms a whole, sharing the same material and the same energy.

This reconstruction of the links between man and nature, disconnected by industrial society, began in the 1960s. Born in 1947 in a Piedmont village, Penone was the son and grandson of farmers. He studied at the fine arts school in Turin, where he soon distanced himself from fashionable minimalist art with its fascination for industrial materials. His attraction to natural materials and his corporal approach to art, influenced by the theatre of Jerzy Grotowski, caught the attention of critic Germano Celante: the young artist suddenly found himself affiliated to Arte Povera.

“My work was the logical consequence of thinking that rejected consumer society and sought relationships of affinity with the material”, he explains. It was at this point that Penone made a manifesto piece, hollowing out a wooden beam to find the veins of the tree it had once been, a gesture that saved the beam from its status as an object to give it back to nature, inversing the timeworn process of separation.

Seated against his apple tree, Penone squints into the sun. Only a few crows’ feet betray his age, evoking the growth rings of trees which have become a leitmotif in his work.

During FIAC 2019, at the Palais d’Iéna, he is showing Matrice di linfa (Sap Matrix), a monumental 43 m-long sculpture: to make it, he took a 100-year old conifer from the Vallée des Merveilles in the Alps, cut it lengthwise and gouged it out to extract the rings. Red resin, evoking human blood, flows through its heart, fluctuating according to the hollows and the curves of the trunk’s landscape, which is punctuated with pieces in terracotta bearing the imprint of Penone’s body.

“Sculpture”, he says, “is about working with matter, the soft, the hard, the solid, the fluid… But when you think about it, everything is fluid. Nothing is stable or fixed. It’s obvious with a tree, but with a stone much less so in our culture. And yet scientific discoveries confirm this ancestral intuition: inanimate objects are just as animate as plant and animal life”. Animus in Latin means the soul and the mind.

And it’s this very soul, present in everything, that Penone strives to render visible – Penone, the artist, the artisan, the man from the countryside, who observes nature in his sylvan workshop of an estate. “The work of art is based in stupor”, he once wrote, “Stupor is a word that, in a very strong sense, means amazement. If we don’t have the capacity to be amazed by the things of this world, we cannot create a work of art”.

Matrice di linfa, Galerie Marian Goodman (FIAC), from 15 to 27 october, Palais d’Iéna, Paris.