“I’m always asked why I still paint.” Dragging on at least his tenth cigarette since we sat down to talk in his Antwerp studio, Luc Tuymans looks me straight in the eye. “Because I’m not stupid.”

His words, like his paintings, take time to comprehend. In Venice, for example, he’s laid a mosaic on the floor of the atrium at the Palazzo Grassi: visitors walk over it, dazzled by the shimmering tesserae whose hues echo the marble surroundings. It’s only later, from the upper floors, that they make out its subject – a stand of darkgreen trees on a pale background. And it’s only on considering the work’s title – Schwarzheide – that they glean a clue to its origin: the Schwarzheide camp housed Jewish slave labourers during World War II, some of whom secretly made artworks which they cut into strips so as to hide them – Tuymans’s work is based on a reconstituted drawing by Alfred Kantor. By the time you’re upstairs, the perverse mechanics of his piece have already caught you in their grip: in total ignorance, you trampled over the horrors of war, and perhaps even marvelled at their beauty. Now you’ve cottoned on, is the work less beautiful?

>> FIND THE FULL TEXT IN NUMERO ART 4 <<

>> ORDER IT NOW <<

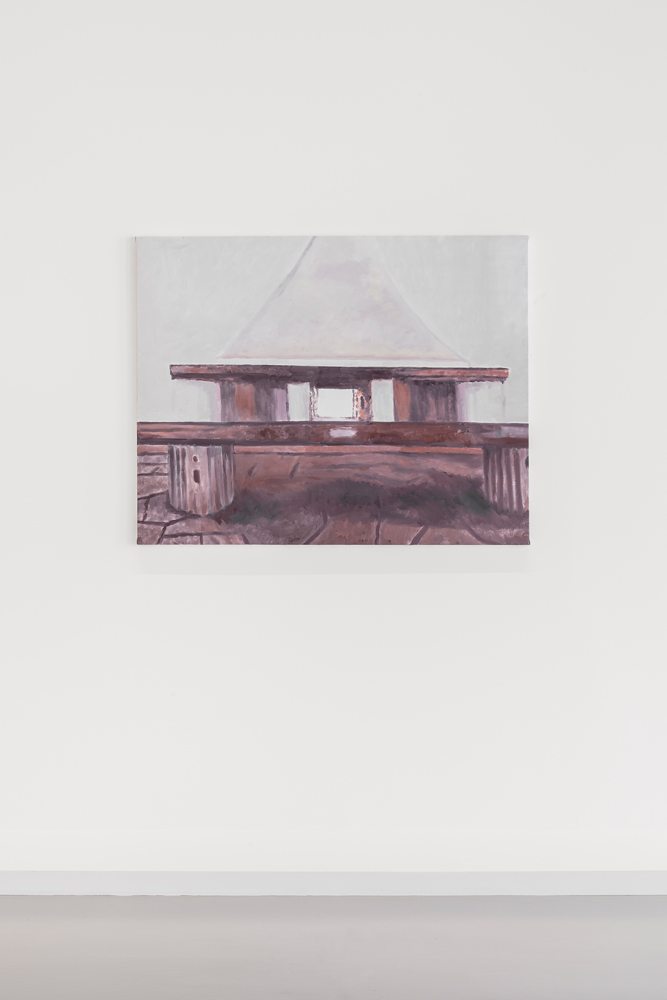

Born in 1958, Tuymans studied fine art in Belgium before briefly abandoning painting for film. He came back to art in the mid-1980s, becoming one of the main figures in the revival of painting. His method is invariable: canvases are realized in just one day, generally a Thursday, from a prexistant image, most often a Polaroid or an iPhone photo. “Because an iPhone photo is almost as ugly as a Polaroid,” he says. “And the Polaroid is an emulsion, it develops like the way I paint – first the lightest hues, then the more contrasted zones.”

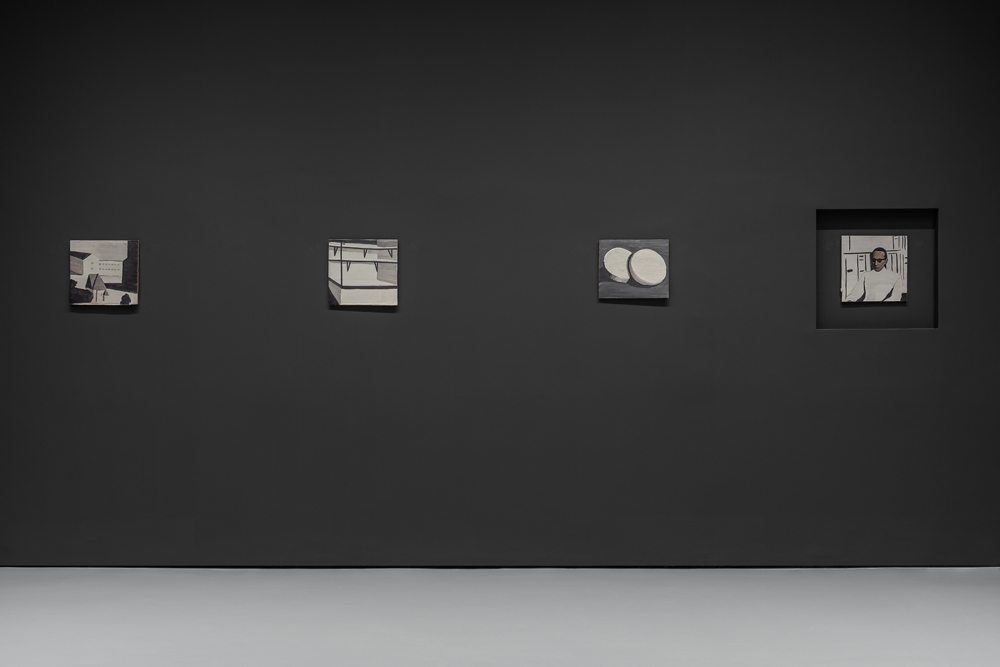

With its 83 works, Tuymans’s exhibition-event at the Pinault Collection allows us to understand his style – its muted tones (“I need a lot of colours to get to these grisailles”), its flattened perspectives (even if he rejects the term), his figures and landscapes that become more abstract as one approaches them. “I really like abstract painting,” he says. “But I’m not like Rothko who wanted people to cry in front of his works. Actually I find that a bit stupid.” Tuymans chooses his subjects from the vast database in his studio and from memory, images that work on his mind until they become ripe for a canvas – once again, a question of time. His sources are diverse: a dehumanized child’s face from the 1960 film Village of the Damned (The Valley, 2007); a smartphone shot of a documentary about the Japanese cannibal Issei Sagawa (Issei Sagawa, 2014).

>> FIND THE FULL TEXT IN NUMERO ART 4 <<

>> ORDER IT NOW <<