Numéro art: Francesco, what is it about Mahmood that made you want to work with him?

Francesco Vezzoli: Pop music has always been my “madeleine de Proust.” I’d even go as far to say my “malédiction de Proust,” because pop music and pop culture in general affect me constantly. Italian pop music, like French, suffered from Anglo-Saxon domination after World War II: Italy only managed to export artists whose music was somehow linked to opera, i.e. Italy’s last great musical era. Obviously there were other forms – Neapolitan music for example – but in a world where everything tends towards simplification, opera remains the ultimate reference when you say “Italy.” I call this the “Bocelli theory” because Andrea Bocelli conquered the world with a style that was largely inspired by the melodramatic tradition of opera.

Does Mahmood contradict or support this theory?

FV: Mahmood is an exciting musical artist precisely because he makes the operatic mode contemporary, embracing urban music, with its Mediterranean and Arab roots, which he sings in the style of opera. Mahmood modulates his voice and can go from a falsetto to bel canto. He reminds me of Maria Callas and her obsession with bel canto, this search for timbre, this mix of vocal virtuosity and the use of ornamentation, nuances and vocalizations over a vast range. But even more than that, the themes he deals with in his music are melodramatic. His hit Rapide is a long monologue expressing the pain of a man who’s lost his love: singing about male despair and deep feelings is a staple of opera. And up till now I hadn’t found many examples of “masculine” melodramatic feeling being expressed in pop music...

“Being sentimental is much more radical than being gay. On Instagram, there's more biceps than tears.” Francesco Vezzoli

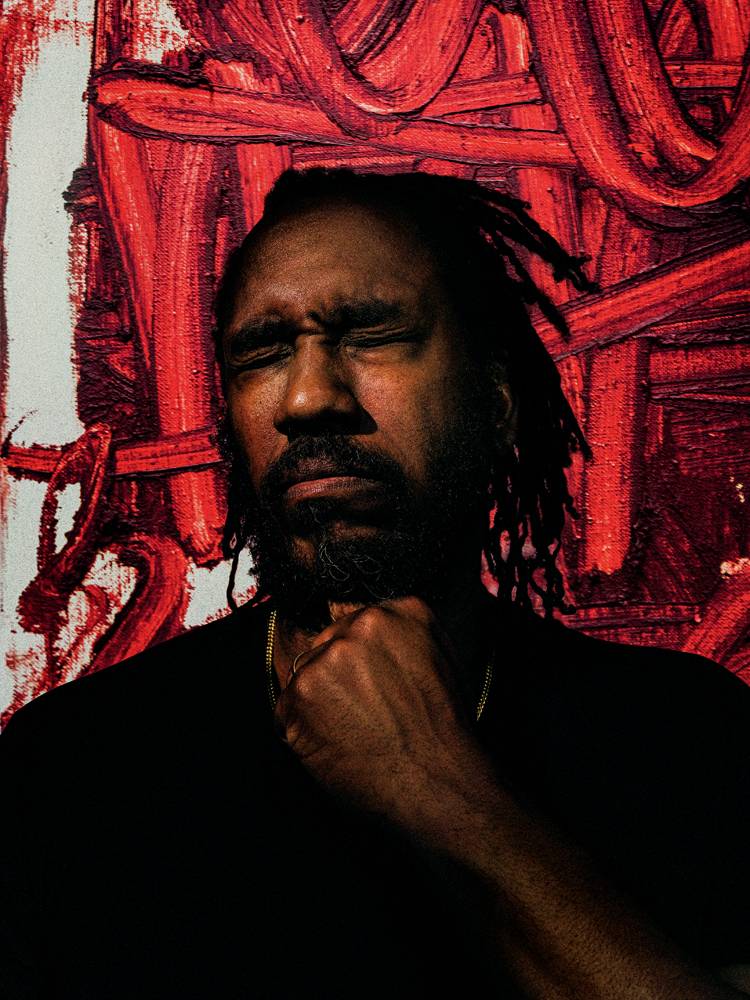

Mahmood, you’ve described yourself as 100% Italian. Are you a symbol of contemporary Italy?

Mahmood: People often try to define my music or to pigeon-hole it. I call what I do “Morocco Pop” – it’s neither pop, nor hip-hop, nor trap. Morocco Pop doesn’t actually exist, but the term encapsulates my need to free myself from existing musical classifications and do my own thing. Lots of people have wanted to make me into a political symbol in Italy, because of my origins, etc. But I’m happy just to represent others like me, young people who work hard to make their dreams come true in this country. I was born in Gratosoglio, south of Milan, where I grew up alone with my mother. We didn’t have much money at the end. My mother couldn’t find a job but still supported me. She believed in me and in my music. When I was three years old, she found me in front of the TV singing and dancing. Now I’m successful, I just want to give her back everything she gave me for last 27 years.

When did you start studying music? Is your technique innate or did you learn it?

M: I started studying music and writing songs when I was 12. I learned classical techniques through piano and singing lessons, but the first CD I bought was the Fugees’ The Score. Being Lauryn Hill’s support act [in 2019] was a dream come true. My other role models were Stevie Wonder and Prince, of course. It was only later that I listened to the great Italian singers like Lucio Dalla, Lucio Battisti and Paolo Conte – a true genius. Through them, I learned how to shape a true Italian song and could start writing for other Italian artists like Marco Mengoni, Elodie, and various rappers.

How has Arab music influenced you?

M: My mother was into European classical music, whereas my father listened to Egyptian music and Arab singers. Early on I begin mixing the two in my head. Sherine was my father’s favourite: I still often sing Sabri Aleel, one of her hits in Egypt. My track Soldi has an Arabic phrase my father always used when I was playing with my cousins: “It’s time to go home.” I wanted to include it in the song so that I’d always be reminded of the image of my father.

“We live in a time when we are all Mahmood and Montesquiou at the same time. On Instagram, all that vanity, all that glitter... People don't know it, but it comes from Montesquiou…” Francesco Vezzoli

Your version of masculinity is miles from the stereotypes of hip-hop, for example...

M: Masculinity can take on many different forms. It’s important for me not to reject any aspect of it.

FV: What I’m about to say now is provocation but I’m willling to own it. Masculinity, and sexual orientation even more, are extremely complicated subjects in Italy. Being sentimental is much more radical than being gay. When you go on Instagram, gay Italians behave exactly like heterosexuals and follow the same set of values: body worship, power, money... There is no room for pain or emotion. On Instagram, there are more biceps than tears.

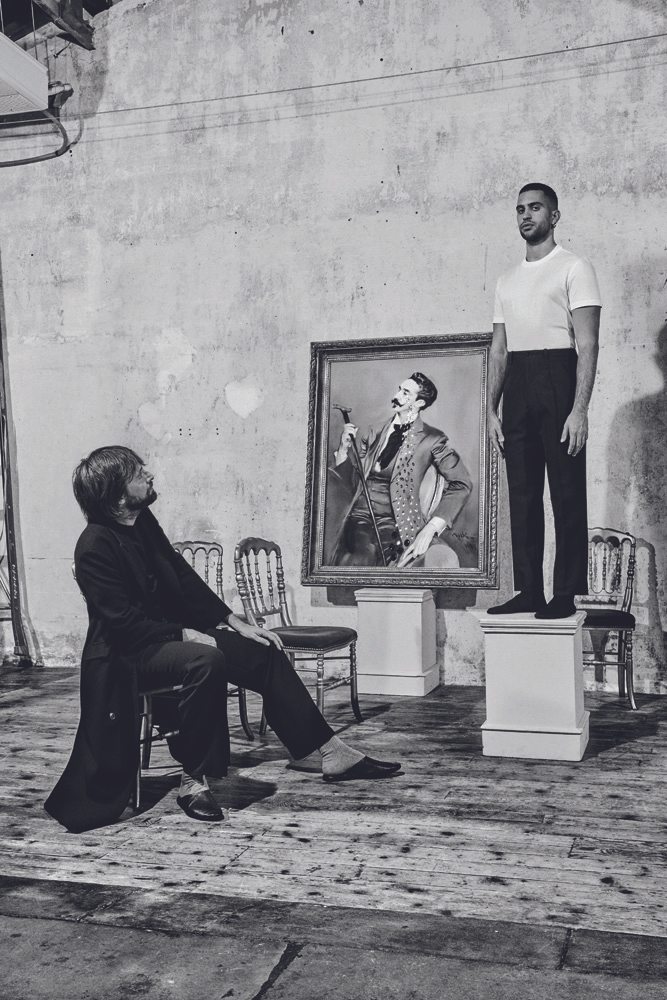

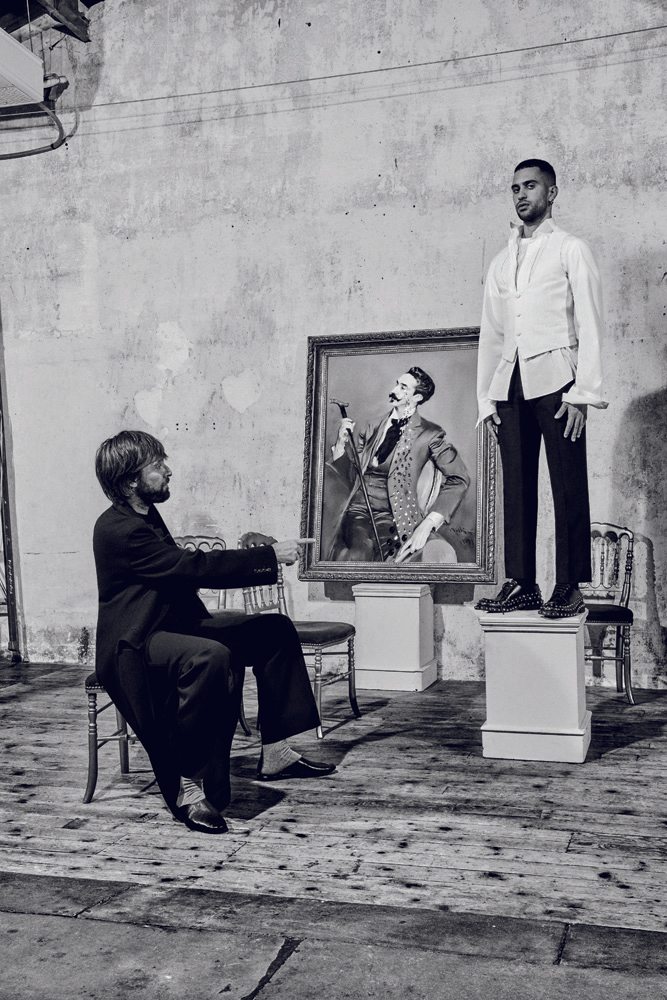

For Numéro art, you’ve styled Mahmood in the manner of French dandy and aesthete Robert de Montesquiou. You’ve even posed him in front of Bolidini’s famous portrait of Montesquiou. Why draw this parallel?

FV: Montesquiou embodied an extreme sophistication that mixed literature, art history and a very aristocratic style of dress. I couldn’t think of anyone more different than an Italian singer like Mahmood. I like the idea of bringing together two such opposites, one who wears only suits, the other only tracksuits. When I was young, I was fascinated by those fairground attractions where you put your head through a cut-out and have your photo taken on someone else’s body. I dressed Mahmood in the most beautiful suit imaginable, holding a cane like Montesquiou’s. This fusion creates a perfectly contemporary iconography. Today we’re all Mahmood and Montesquiou at once, on Instagram there’s all this vanity and glitter... People don’t know it, but that comes from Montesquiou. By merging these two traditions, I’ve created a conceptual snapshot of our times.