Numéro art: Can you describe the new Pace Gallery?

Marc Glimcher: There’s a library on the ground floor, storage space on the second, three floors of exhibition space, a terrace that is a full floor on the second-to-top level, and at the top, over the terrace, a performance space with a music system, which will also host lectures, teaching events, etc. That’s eight levels altogether – it’s huge! But then we do represent 90 artists.

Wow, an enternaiment space!

We don’t use that word. There’ll also be food here, but not a big restaurant with reservations, rather a food truck.

So what’s behind this giant new building?

Firstly, our lease was up on the old one. We started this process, and then I started fantasizing about having everyone in the same building. But the gallery’s audience has also grown enormously, not just the number of collectors but also the number of people for whom contemporary art is an important part of their lives. Since Pace first opened in 1960, and especially since turn of the millennium, it’s become insane. Nobody has exact figures, but it says something if I tell you we have 800,000 Instagram followers! The place of contemporary art in the world has become so much bigger, the demand is bigger, the number of collectors is bigger, so the job the artists have to do is bigger. The artists have to work in bigger studios and don’t have time to answer phone calls. Running a gallery has also turned into a massive job.

Do you have annual attendance figures?

Yes, 100,000 in New York alone.

What were the figures 20 years ago?

I’d say 8,000 to 10,000 people.

“Fairs are a kind of anti-art thing, because to go in somewhere and see thousands of works of art in the same place is not a good idea. ”

Like many other galleries, you’ve moved to a huge space in a context where retail sales have actually gone down. What part has the internet played in this?

In 3,500 BCE, artists invented the experience we call art. Now, one of the huge collaterals of the internet is the experience of art: because people sit in the virtual world for so long, they need real-life experiences. The fact that demand for art has gone up confuses the business community, because retail sales in shopping malls keep going down, so they tell themselves, “People stay at home now.” But, while the brand experience can be replicated online, the art experience can’t. Art is irreplaceable.

What do you think about art fairs?

There isn’t that much good art. Fairs are a kind of anti-art thing, because to go in somewhere and see thousands of works of art in the same place is not a good idea. Having said that, what’s great about art fairs, and which makes up for all the terrible things about them – too intense, too much art, too commercial – is that there’s a place where everything and everyone come together.

I guess Pace has galleries all over the world?

One fewer, sadly, since we’ve had to close Beijing. It was much harder that we envisioned, and I don’t only mean to sell art – because it was extremely hard to sell art in China – but also because the atmosphere there is very tough. Our lease was up, and we feel there’s a better plan for business with China, which we’re working on right now. So, without Beijing, we currently have two places in Hong Kong, one in Seoul, one in London, one in Geneva, one in Palo Alto and five in New York. That makes us present in six cities across the globe today.

Have you thought about opening in Paris? So many of your competitors have.

I’m a little wary about opening new spaces in cities where there are already a lot of galleries that the city is very supportive I’m really excited about opening in smaller cities.

Do you feel like artists’ mindsets have changed since you started in the business?

Yes. Before, none of the artists were thinking about their careers, now they’ve all become totally careerist. But artists always had a career, they don’t do it for charity. You’re an artist because at some point somebody decides they’re actually going to purchase something of yours that has real economic value.

“Neither museums nor auction houses are playing their role.”

So what happened to make things change?

What happened? We had some real-estate developers and retail people as our collectors. These were people who were told by their parents: “Buy something to hold onto for future generations. This building, this piece of property, you pass it on to your kids, then they leave it to their kids”. It’s an investment in the value of things, and we had stuff in which they could invest – you pass this brand on, for ever and ever. Then collectors started to trade the works they owned, which began to change things for the artists themselves. The audience, the collector and the patron all impact the artist just as the artist impacts them.

So what are artists like now? They seem to be much more in contact with their collectors for one.

Oh yeah. Our old job was to be the ones building communication between artists in their world and collectors in theirs, because those worlds were so far apart. But that’s not the case anymore. Why do people buy art? That’s the big change. People used to buy art so they could feel separate from others, expressing their wealth and power through their art collection – them and us. Now people buy art to be part of the world that we created.

Not forgetting the competitive “my collection is bigger than yours” attitude too.

Now it’s more like “my community involvement, action, engagement, etc. is bigger than yours.” That’s how you get a $20 million-per-day market.

So you’re building this huge new space to show painting, sculpture, performance, etc. – apart from the profit, how does that differ from a museum?

We’re not selling tickets, so we didn’t build it to develop a new economy. We are advocates, and the funny thing is that museums are becoming advocates too, but that’s their of. It’s the case in Paris and Los Angeles. We had an office in Paris for a while but then it moved to Geneva. give back. It is still somehow considered illegitimate for an artist to be paid by the public.

In Palo Alto, at one point, you charged admission for visitors. Is that the future for galleries?

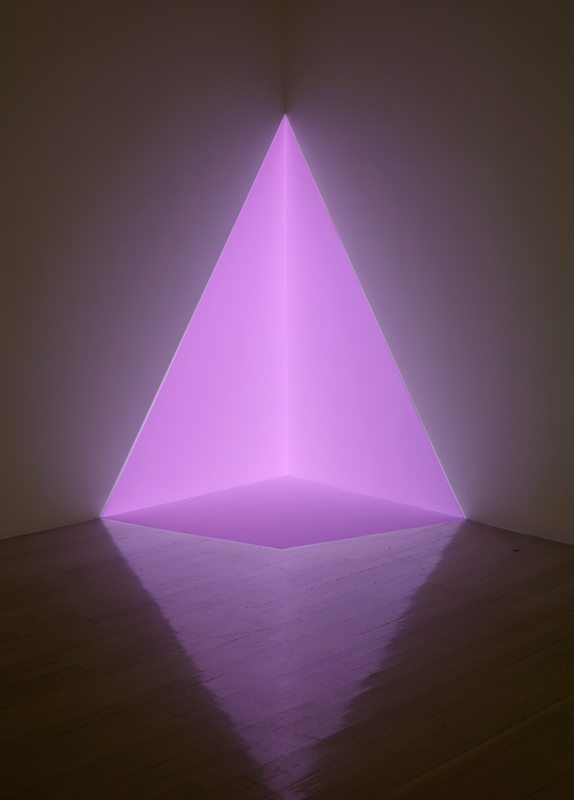

It’s the future of art, not galleries. Galleries are at peace being what they are, but there are artists now who started in the 60s who don’t want to make objects, they want to make experiences and environments. They don’t want to be paid by selling souvenirs, nor by begging and borrowing from patrons. They’d like to be paid the way a singer, a filmmaker or a dancer is paid, by the people who experience what they do. Museums can get paid, but they can’t give back. It is still somehow considered illegitimate for an artist to be paid by the public.

Are artists coming to you saying, “We want you to charge admission for my environment”?

There are artists who have been doing that for a while. They came to us saying, “We charge tickets for this,” and we were like, “What are you talking about? Impossible!” And then they said, “Well we won’t do the show with you.” This was with the Japanese art collective teamLab. So we quickly sat down to have a conversation with them about it. There’s an argument that goes, “If it’s commodified it’s not art,” but actually you can’t stand by any of those positions that make it untenable to sell tickets. I think these two things have to be done seperately. Meaning that you’ll never have to pay to come see an Agnes Martin show, but if, in our new building, we had a teamLab show…

So you sold tickets for $20 each and apparently got 250,000 visitors?

Yes, and then it went to Beijing where we got half a million visitors in five months.

“Robert Irwin said, “Artists will stop making objets and start making phenomena”.”

Do you think it’s because it’s Japanese, not American?

No, it’s because it was amazing. The reason we “only” got 250,000 people in Palo Alto is because that’s all the people who were available there to come.

And out of all these people, how many actually buy art?

Well, we have 800,000 Instagram followers and 1,000 clients. So who are the 799,000 other people?

Have you done demographic studies like museums do?

We do them all the time.

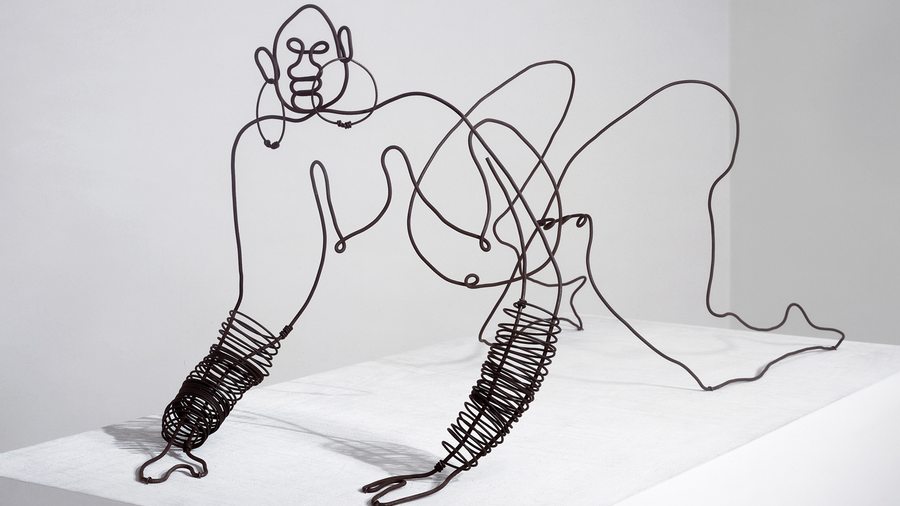

Yeah I was asked my zip code when I walked in... Among the environment-creating artists you represent are James Turrell and Robert Irwin...

We started representing Turrell in 1965. It was Turrell and Irwin who had this whole idea. When I was a kid, Irwin said, “Artists will stop making objets and start making phenomena. They will stop making things to put on the walls, and will start being urban eschatologists who create an experience of what we’re going to see.” I just came back from London, where we did our first project of this kind with Leo Villareal, who has lit up four London bridges. Where could you see this kind of thing except in situ? It’s super subtle, incredibly beautiful – you can’t really see it online.

So Pace is a museum, publishing company and entertainment firm all rolled into one. The only thing you don’tdo is hold auctions !

Exactly, and we shouldn’t, because auctions should be like museums: the honest and unbiased art world. But currently they’re not. Neither museums nor auction houses are playing their role. If we have no arbitors in the system, if everybody is a salesman, that’s really bad. Art auction houses are completely biased, they’re marketing the hell out of things. It’s not their job, it’s their job to do the opposite, to let it rise or fall as it will. As a result, we no longer have a real sense of the art market. We, the galleries, are busy pushing, selling, convincing, cajoling, while the auction houses and museums are also out there selling artists, which traditionally was exclusively our job and not theirs.

What’s the future for the art ecosystem ?

Most galleries are building these artist ecosystems underneath the deal. There’s a bunch of people whose job is to go to the artist’s studio, take care of the artists, and then the dealer is supposed to sell. I think it’s a terrible system, because you want your dealers to be in the artist’s studio, to be the person who’s there, but you do need people with a bigger view. So we’re building a curatorial view in the gallery, where we’re bringing in a bunch of curators.

“Curators have so much power nowadays. We saw dealers losing power to curators”

You mean museum curators?

Yes. We hired Andria Hickey, who was the chief curator at MOCA Cleveland – she’s an amazing person. We also hired Mark Beasley, who’s coming from the Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington.

So you’re really reshaping things to meet this new audience. You’re like the salesman, and these new hires are going to be…

We sell the art and accompany the artists. The curators are goint bo be the ones who’ll be thinking about the global picture.

That’s fascinating. Is this approach a totally new thing for you?

Yes. Curators have so much power nowadays. We saw dealers losing power to curators, not only because curators are moving out of museums and into all sorts of other roles, but also in the sense that they represent a group of people who have taken over the narrative.

Your father, Arne Glimcher, who founded Pace back in 1960, was one of the first to hire people like Bernice Rose, a curator at MoMA…

My father did absolutely everything first: when all the other galleries were just selling paintings, he hired Bernice Rose, and he also did museum-type shows in the 1970s, among them the landmark 1978 exhibition The Grid: Format and Image in Twentieth Century Art, which became his most amous show…

You’re perhaps doing it in a more 21st-century way, though... But it really is fascinating how galleries are becoming more and more like museums.

But look at how successful museums are! They’ve even become the number-one venues for fashion exhibitions today. Their audiences run to the tens if not hundreds of millions, they do billion-dollar packages! They may be crying poor, but why in that case are they becoming the biggest, most powerful destinations in every city? There’s a very definite reason for that!

Pace Gallery, open since September 14th, New York.