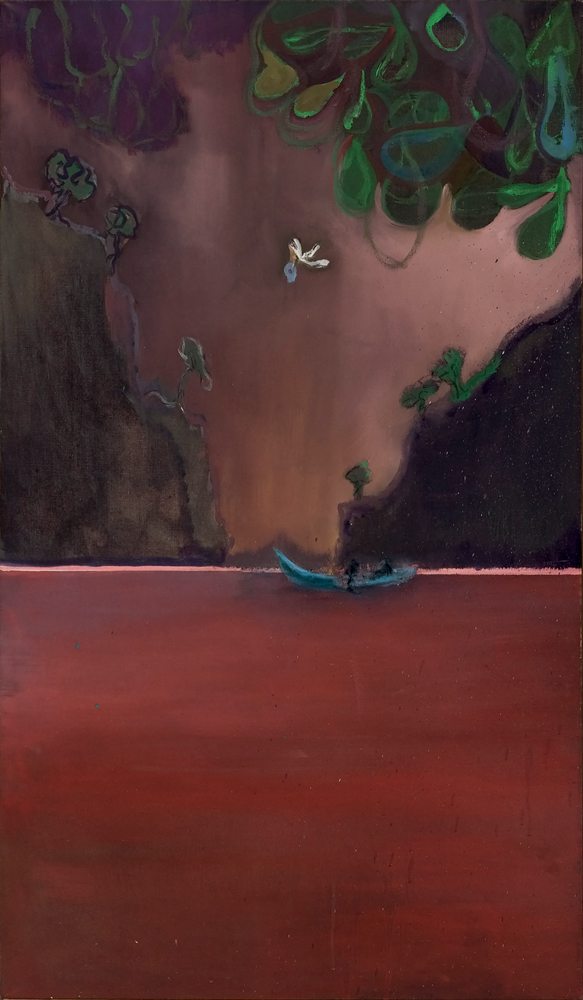

When Peter Doig burst onto the London scene in the early 90s, the art world was in a state of uproar. The Young British Artists, led by Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas and Tracey Emin, turned the tables with provocative and conceptual works. Among them, Doig appeared as an outlier, with his figurative painting style whose references ranged from Edvard Munch to Paul Gauguin, but that didn’t stop him from gaining unanimous international recognition. His large‐scale paintings fascinate in their ability to evoke dreamlike, mournful, nostalgic and melancholy landscapes where figures lose themselves as though facing their own solitude. Above all, Doig impresses with his brilliant handling of colour, the way he plays with contrast and gradient, and his extraordinary pictorial inventiveness, which finds inspiration in art history and pop culture, as well as in his own photographs – stills from the film Friday the 13th were the inspiration behind two of his most famous paintings, Echo Lake and Swamped.

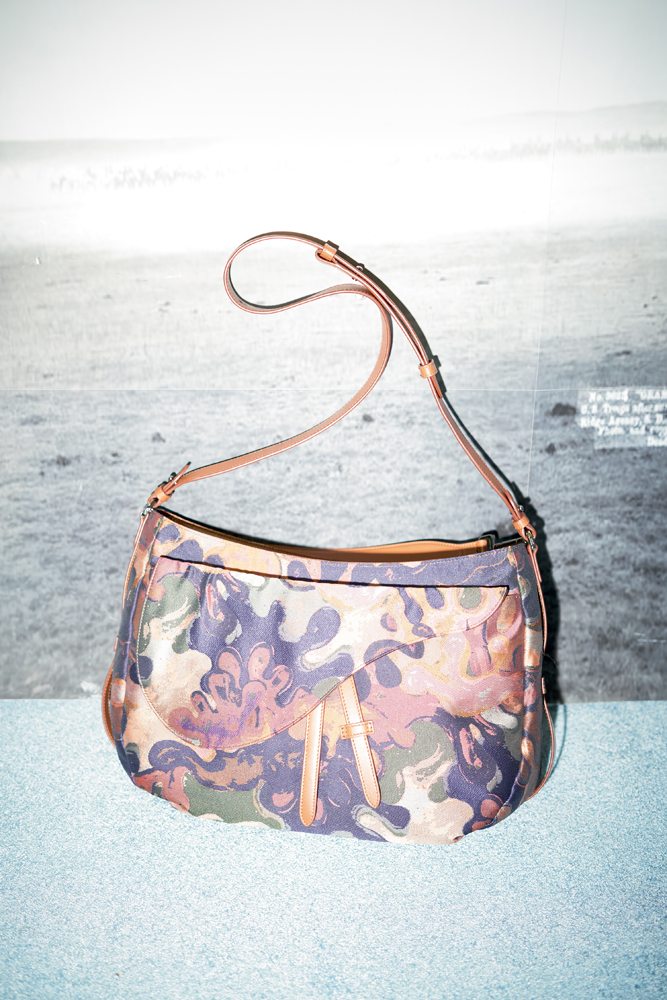

After the turn of the millennium, Doig began to make headlines as one of the most expensive living artists in the world. In 2007, his famous White Canoe sold for $11.3 million at Sotheby’s; ten years later, a new record was set at Phillips New York with Rosedale (1991), which went for $28.81 million. More recently, the radiant power of his works seduced Kim Jones, artistic director at Dior menswear. Though Jones is a well‐known art lover, and this is far from his first collaboration with a contemporary artist, the dialogue with Doig for the autumn/winter 2021/22 collection stands out. From hats and garments to the reproduction of details of his masterpieces or the chromatic manipulation of fabric, the exercise forced Doig to look back, prompting a reflection on the place held by clothing in his oeuvre and, of course, on the relevance of translating artworks into fashion.

Numéro art: What piqued your interest in working on a fashion collection?

Peter Doig: To be honest, I was a bit hesitant at first. I’m not sure that collaborations between fashion and art are always terribly interesting, especially if it’s only about putting an image on a shirt or selling an overpriced sweater. I didn’t want to just plonk a Dior logo somewhere or design T‐shirts from my paintings, I wanted to think about the colours, their association, and to start from, for example, a detail of a painting in order to create a dialogue with the garment. All doubt disappeared the moment I met Kim Jones – our similarities go beyond the strict realm of fashion, and we share an obsession with colour and with certain artists, musicians and writers. More importantly, Kim came with an idea. He had selected a figure from my painting Gasthof who is wearing an 18th‐century military uniform, inspired by a ballet costume. Kim had started to play around with this figure using some very theatrical clothing. That was my gateway into the project. I plunged back into what had originally inspired the picture, and then looked at the different types of clothing I’d painted during my career. I’d never thought of them in terms of fashion. They were primarily present on the canvas as visual elements that were part of its construction. I then looked at all of the details of these painted garments – a hat, a pattern…

What role does clothing play in your paintings? Is it purely visual or does it also indicate the origin or social status of the figure in question?

Clothing has a fundamental role in a picture. Take Manet: the body language and costumes are what help make his work convincing. Without it, a painting fails. I once explained to a student – a good painter, but who paid too little attention to detail – that he needed to give more information. What is your figure wearing? What style of shoes? That’s the sort of thing that makes the canvas come alive. The figures must have substance, otherwise they remain a mere creation in the painter’s mind.

What type of characters interest you? We already know how much pop culture has influenced you…

I take a lot of photographs. And even though I’m not super organized, I manage to put aside portraits of people who interest me. In my most recent paintings – one of which was used for a camouflage sweatshirt – the figures come from different sources: two of them had been photographed in New York and another came from a film I made in Trinidad... Everything was in their expressions. Their coming together on the canvas had to create a story, and I needed the right face for it. For the one in the middle, for example, the attitude wasn’t right, and in the end I had to change the face based on a much older photo I had taken.

Is the word “sampling” appropriate here?

It’s a pretty classic way of working for artists of my generation. You could probably say the same thing about Kim Jones. To be fair, you could say that artists were sampling well before the word was invented. An exhibition at the Louvre in 1993, Copier Créer, had a big impact on me. It was all about the idea that the museum had been used by artists to copy other works – Matisse copied Géricault, etc. It was fascinating. The difference with today is that borrowing and sampling are much more upfront.

When you started painting, figurative art had completely fallen from grace. What meaning did it have for you?

Painting makes visible what we cannot see. It may sound pretentious, but it’s true. If you close your eyes and think of a man on a beach, for example, you can see something in your mind’s eye. And it’s that vision, that no one else can see, that interests me. I don’t try to paint dreams or specific images, even if I’m sometimes inspired by them. What excites me are the images that come from our mind. I want to make them visible, real. With a phone, you can capture what you see in just a click. But how can you do that with what’s in your head, if not through painting? These mental images are fascinating because they are created in successive layers over a long period of time. Image accumulates on image, colour on colour. I’ve also always been interested in what painting allows you to do technically in its material aspect. What changed between Matisse and me is that there was Abstract Expressionism, minimalism and all sorts of other movements that brought new references, new techniques, and therefore allowed for new possibilities in painting.

Thanks to Dior, you got to look back over your previous work. What developments did you notice?

Figurative painting has become the dominant art form and I don’t know if that’s a good thing. Most paintings you see in galleries are pretty unremarkable. Thirty years ago, figurative painting was subversive. I wanted to challenge the norm. That’s why I decided to do large‐scale paintings that were romantic and nostalgic. The scale and size were a way to challenge everything I had seen. In the end, it was a gallery specializing in minimal art that offered me my first exhibition. Many of its artists left because of me!

Are the pieces made with Kim Jones works of art?

When he, I and Stephen Jones, who designed some amazing hats for the collection, began our studies, we were all artists, we all drew. In my day, a lot of very innovative things came out of the fashion departments.