He’s one of the greatest American painters of the 20th century, and his influence is not only felt in the work of, but is also claimed by, painters of the 21st century, from Brian Calvin to Joe Bradley. During his 50- year career, he was in turn a realist painter, an abstract painter and a figurative painter, and his talent was hailed whatever style he chose to experiment with. An explorer and researcher, looking for form, trying out styles, Philip Guston was a true inventor, as were all the avant-garde artists in an era that now seems so distant, merciless as they were in their boundless creativity. “The act of painting is like a trial in which all the roles are played by the same per- son,” Guston once said. “The canvas is the courthouse while the artist is the prosecutor, defence attorney, judge and jury.” Exactly 40 years after his death in 1980, the big retrospective of his work that was meant to open this summer and travel round the US and the UK has been postponed until 2024. Which goes to show, yet again, that when the art world gets caught in its own trap, the very idea of art collapses.

From New York’s Whitney to its MoMA, from Chicago’s Art Institute to the museums of Denver, Houston, LA, Memphis, San Francisco and Washington, from Paris’s Centre Pompidou (repository of the splendid 1971 In Bed) to London’s Tate Modern, Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria, Copenhagen’s Louisiana Museum, Cologne’s Ludwig Museum and the Tel-Aviv Museum of Art, all the most prestigious artworld institutions on the planet are lucky enough to own works by Philip Guston. You might almost say it’s their duty to own them, so impossible does it seem to recount the history of 20th-century art without including Guston, who was born Phillip Goldstein in 1913 in Montreal, the son of Ukrainian Jews who fled Odessa in 1905, settling first in Canada and then in LA in 1919. Traumatized at the age of 10 by the suicide of his father, whose swinging corpse he discovered in the garden shed, Guston spent much of his childhood shut up in a closet, copying cartoons from the daily pa- pers. “As a child, I would hide in a closet while my older brothers and sisters came with their families to dine on Sunday evenings. I felt safe. Listening to them talk about their health, marriage and financial problems, I felt how much I was distant from their world in my closet, lit by a single bulb. I read and drew in this box that was mine. Certain Sundays I even painted in the closet.”

At the Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles, where he enrolled in 1927, Guston became friendly with one of his classmates, a certain Jackson Pollock. They would be expelled together the following year for publishing a fanzine which, among other things, criticized the omnipresence of sport at the school, and together they went off to live in New York in 1930, where they shared an apartment. Like Pollock’s at that time, Guston’s 1930s painting was at first figurative, before being marked by Picasso and Surrealism, becoming more and more abstract and influenced by Cubism up to 1948. “I had the feeling I’d finished that exploration,” he would later explain. “The following year I destroyed everything I’d done. I felt that everything was a failure and that I could no longer continue with figuration. The forms I wanted to paint could no longer take the form of objects and beings, and I felt I would have to abandon the figurative. It was a long struggle to get there. I felt torn between two allegiances, one to my own past and another to what I could still become.”

Guston’s Red Painting of 1950 is almost a monochrome, and red would become the dominant and almost exclusive colour in his subsequent work. In the 50s, Guston was one of the most talented exponents of Abstract Expressionism, alongside Willem De Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Franz Kline and others. But then he became frustrated with abstract painting. “At the beginning of the 60s, I felt completely torn, almost schizophrenic because of war, be- cause of what was happening in America, the brutality of this world. What sort of man was I to stay home reading magazines, furiously angry about everything, and then go to my studio to add a bit of red to some blue... I said to myself that there had to be a way to act.”

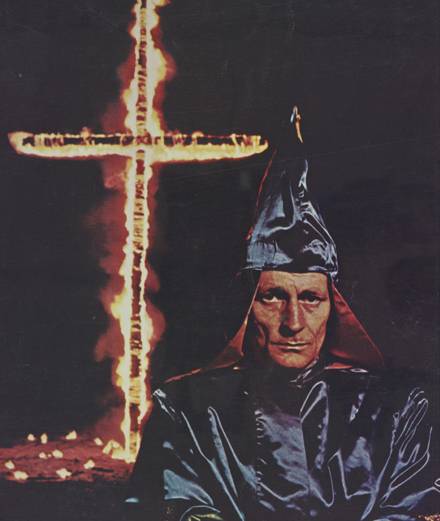

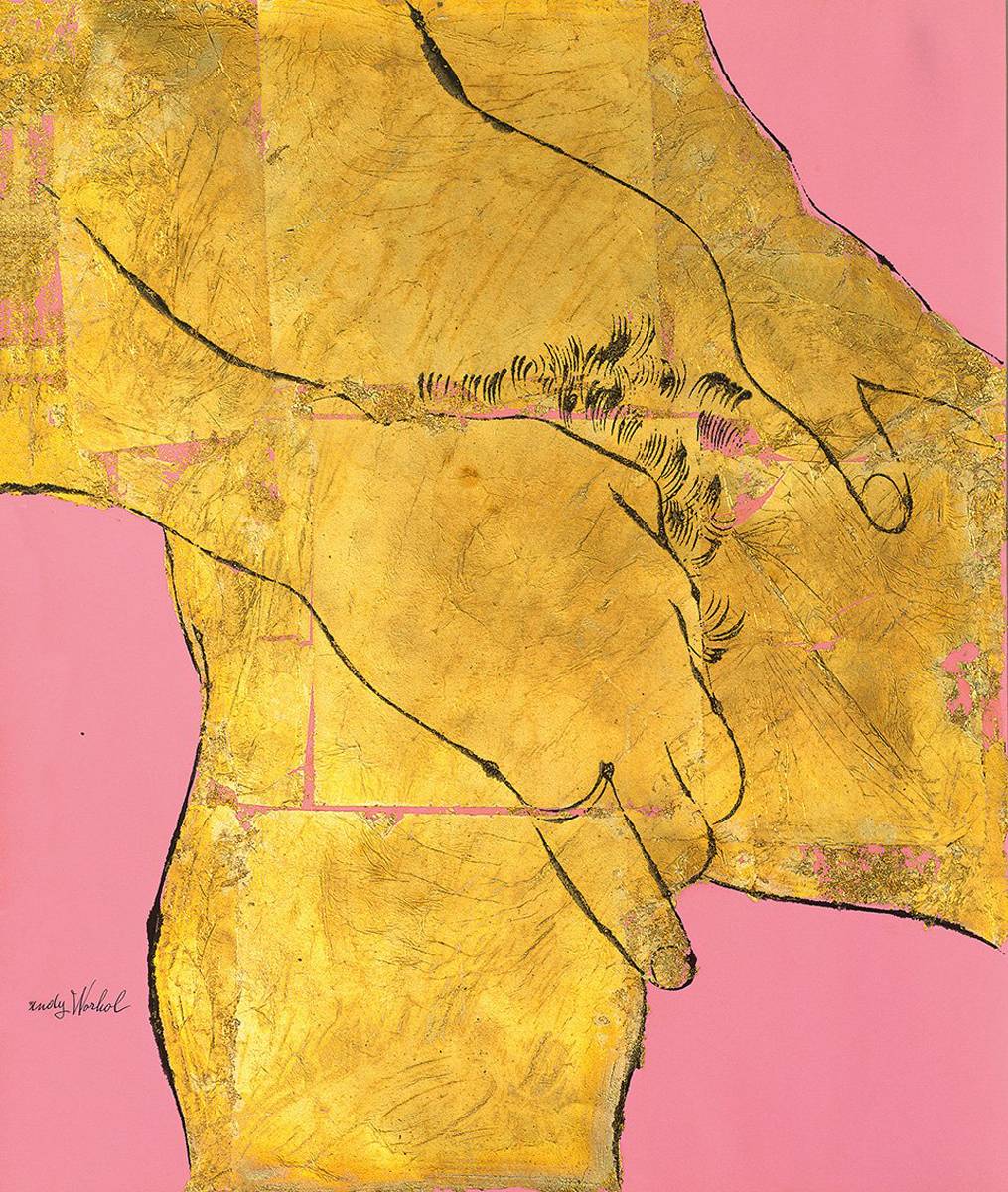

The singular, innovative figurative style that he invented at that time seemed to preserve something of the cartoon strips he used to copy as a child in the closet where he sought refuge. It’s putting it mildly to say that the impertinence of this new style, and in particular the borrowings from cartoon strips, caused a scandal: Guston was thrown out by the Marlborough Gallery in New York just after showing his new work there. He repetitively painted subjects such as shoes, hands, cigarettes, clocks, cars or pointy hoods that resembled those worn by the Ku Klux Klan. In fact, Guston had already represented the violently racist and anti-Semitic white supremacists of the Klan as early as the 1930s (for example in Drawing for Conspirators of 1930, which is held in the collections of the Whitney), and it would become a recurring subject in his painting, a symbol of oppression in general and of violence towards African Americans in particular. With their fat cigars and show-off gas-guzzling cars, his KKK characters are entirely repulsive. In one fell swoop, not only did Guston invent a new plastic vocabulary, he also produced a socially conscious form of painting that evoked all the world’s darkest aspects. The initially negative reaction slowly gave way to unequivocal recognition, particularly among artists, and market values have duly followed: in May 2013 the canvas To Fellini (1958) sold at Christie’s for almost $26 million, double its upper estimate.

Forty years after Guston’s death from a heart attack, art today has decided it has other priorities. Since the turn of the millennium, contemporary art has “democratized” and in doing so has attracted a new, less cultivated way of being seen, works being appreciated not so much for their contribution to the history of form than for what they have to say – a view that seems to forget that art is not some sort of primal communications form akin to advertising. Our era wants art to dish out clear, un- equivocal messages, messages that are often rather obvious and, at bot- tom, tediously banal – war is bad, inequality is awful, etc. And woe betide all those who would seek to put a little complexity into this black-and-white approach. Four decades after he left the land of the living, Guston has paid the price for this spectacular deterioration in the way we look at art. Four years ago, a big retrospective of his work was scheduled by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston and Tate Modern in London. (Those tempted to moan that once again the Centre Pompidou is not on the list would do well to remember that a big Guston retrospective, which travelled to Boston, Stuttgart and Ottawa, was shown at the Pompidou in 2000, with Didier Ottinger as the curator of the Paris leg of the tour.) On 21 September this year, the four institutions re- leased a joint press statement in which they explained that, “After a great deal of reflection and extensive consultation, our four institutions have jointly made the decision to de- lay our successive presentations of Philip Guston Now. We are postponing the exhibition until a time at which we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the centre of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted ... We plan to present a reconsidered Guston exhibition in 2024 and will work together to do so.” The indignation was loud, denouncing quite rightly the insult to gallery-goers, who, one can only deduce, are considered incapable of understanding that a representation of something does not indicate unequivocal agreement with that thing, especially when it was obviously the artist’s intention to denounce said thing – with Guernica, for example, Picasso does not plead the case of war but on the contrary seeks to show it in all its horror. But it probably wasn’t ordinary gallery-goers that the four museums were afraid of – they know full well the public isn’t that stupid. It was more likely the potential reactions of the “cancel culture” brigade that they feared, a gang that currently writes and above all rewrites history their way, deciding what is and what isn’t “degenerate art.”