“I will dance better tomorrow.” This comment, heard* at the exit of Dancing with myself, is possibly the most beautiful that could be made about this exhibition. And true enough, after spending several hours at the Punta della Dogana, rarely have we felt such liberation of a body that can weigh us down and hold us back. Relaxed, we rarely feel such a need to set our bodies in motion. We will dance better for sure… And this isn’t the only effect provoked by the new show from the Pinault Collection, on until December 16th 2018.

Conceived in collaboration with the Museum Folkwang in Essen (who presented a first version in 2016), the exhibition, which brings together 140 works from the 1970s to today, could easily cause misunderstanding. By choosing to look at how artists have used their bodies as a tool and raw material – how they have danced with own bodies to create - Dancing with myself could be perceived as a sort of intellectual masturbation by navel gazing artists. But if the artists' body is present everywhere, it’s because it’s a means of talking about the world. Cindy Sherman, who has two rooms (one devoted to photos done in 2016, and the other to her masterpieces of the 1970s), puts it simply: “I use my body like a mannequin. My photos are not autobiographical.” For decades the American artist has photographed herself in staged settings where she embodies different clichés of femininity. These images, which are clearly constructed, reveal another construction, a social one: that of the codes of a femininity imposed by the male gaze and the situations to which women “must” consent.

The body is a political tool. It reveals clichés through its playing and its irony and its destroying of diktats.

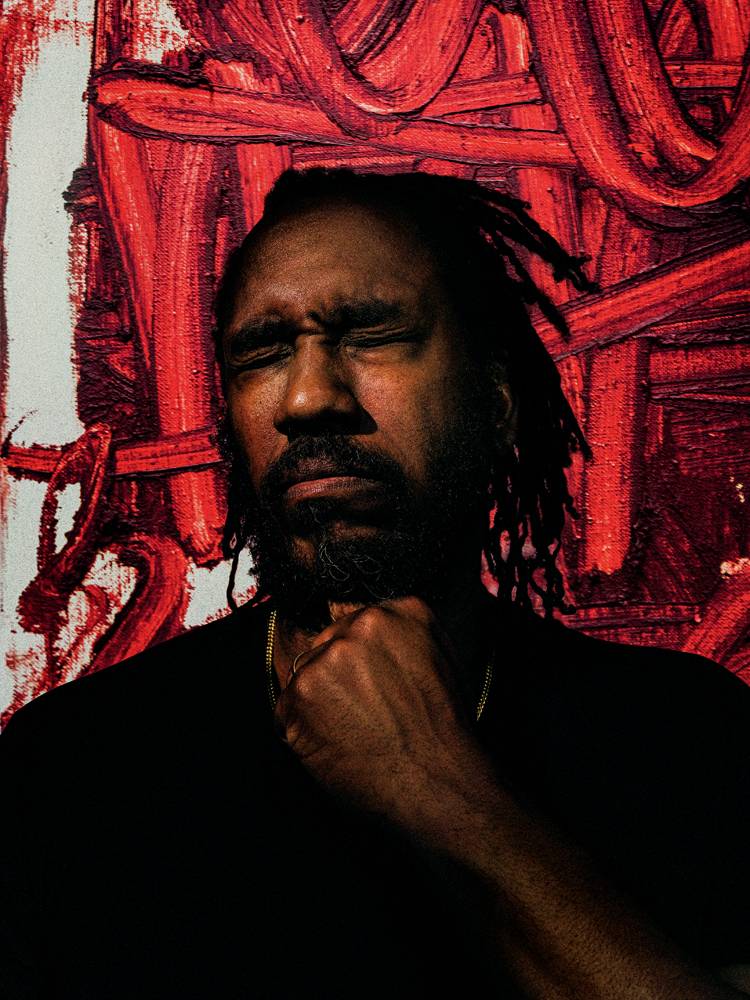

The body of the artist isn’t there to reveal their character or their psychology. The body is a political tool. It reveals clichés through its playing and its irony and its destroying of diktats. This politicised body becomes the primary and essential tool in the struggle: it was the great transformation of work during the second half of the 20th century. And is perhaps maybe the real subject of the exhibition.

The dominance of the white heterosexual male is in decline. He is waiting, slouched, for his own disappearance. It is the end of the body, it's time to mourn its passing.

The curators of the show, Martin Bethenod and Florian Ebner have created one of the most beautiful entries to any exhibition, with the first room combining Félix González-Torres and Urs Fischer. You pass through a gigantic curtain of red and white plastic beads by González-Torres who died very young of AIDS to access Dancing with myself. You must take this step and do this first dance with a curtain that's the very materialisation of the artist's blood. This contaminated blood that scared so many, this “gay cancer” which for years was taboo and kept hidden, is finally rendered visible. It becomes part of our body as we walk through it. Cited in the catalogue, Susan Sontag writes how “although we would all like to present the good passport (to the kingdom of well-being), the day is coming when each of us is forced, even for a short while, to recognise ourselves as citizens of the other region.” This is the passage organised by Félix González-Torres. Because the body is political in its capacity to transmit messages and to shout, “AIDS exists!” Félix González-Torres screams it. But his body-curtain is a tool for political action in its capacity to shove us through to the other side. Forming a community with the most vulnerable.

We cannot help but think of the work Ce que le sida m’a fait by Élisabeth Lebovici. In it the French art critic describes with commitment, the emergence of queer thinking in the 1970s. This queer thinking, profoundly humanist, was a much-awaited attention needed for the most vulnerable. As the complete opposite to miserabilism, it forms a moment of empowerment. By the excluded taking control of their bodies and their history, they take action.

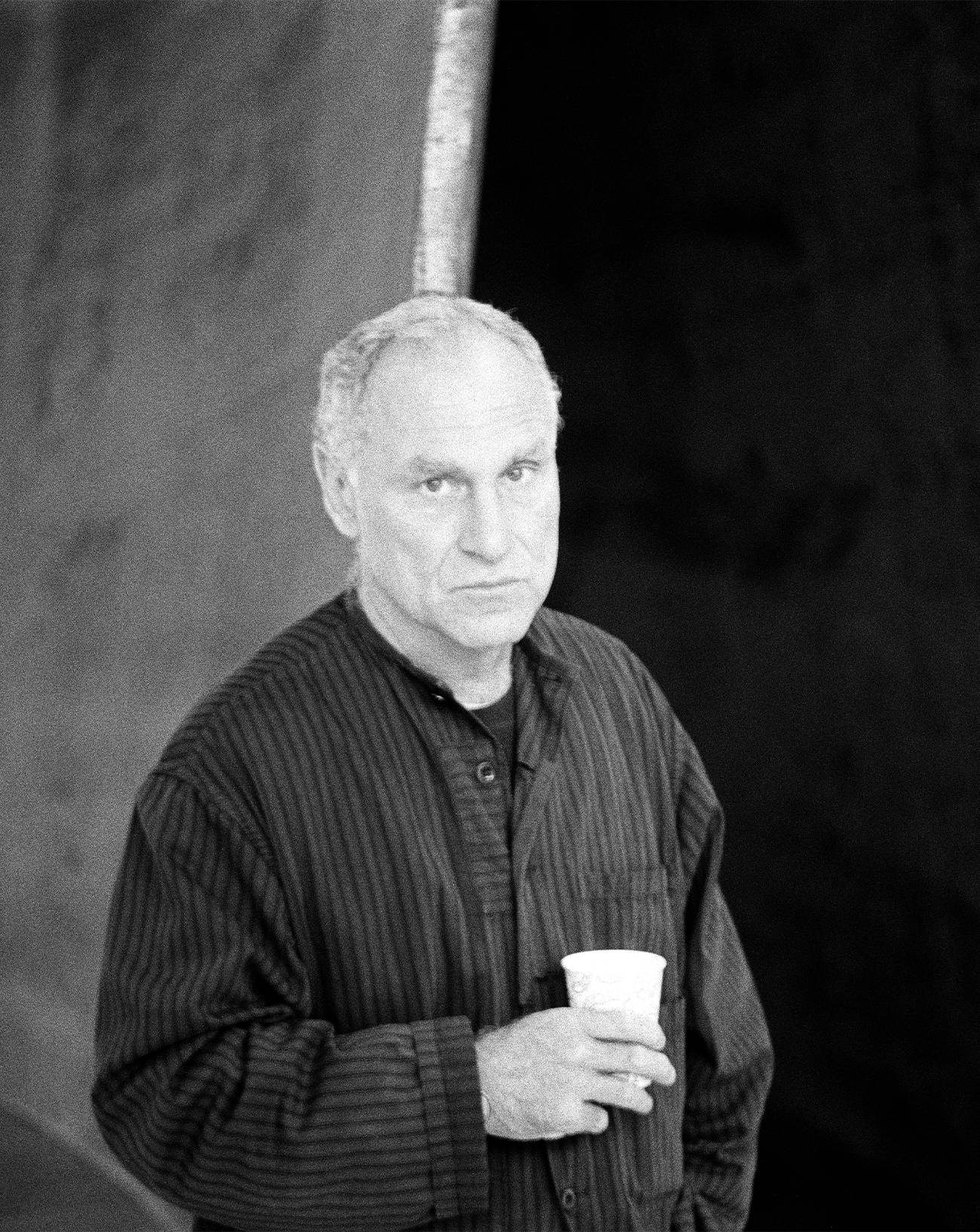

And what do we see through Félix González-Torres’s blood? A wax sculpture of the artist Urs Fischer’s own body. Candles burn. The dominance of the white heterosexual male is in decline. He is waiting, slouched, for his own disappearance. It is the end of the body, it’s time to mourn its passing.

The body is a construction, better, it is a game of construction. The body is fluid, like gender. It is old – dying, it is young. It becomes what it is.

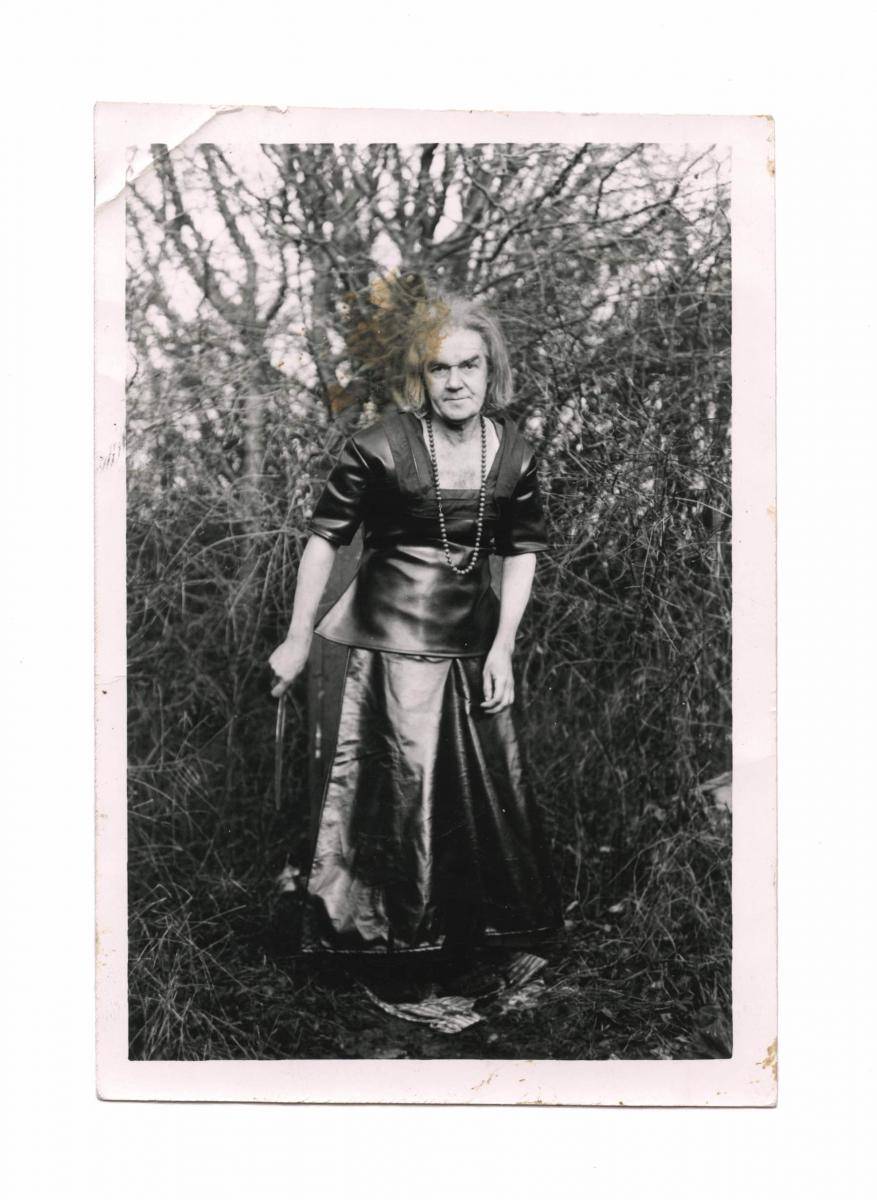

Marcel Bascoulard, a tramp by choice, dresses as a woman and took photos of himself for several decades in Bourges. He chose his fabrics and designed his patterns. Some of his images are on show at the Punta della Dogana.

It’s an identity crisis that goes wider. The 20th century has seen the advent of a world where “I” has fragmented, shattered even. There is no longer an authentic me, but a profusion of masks and roles. “Behind this mask is another. I never manage to reveal all these faces,” wrote the artist Claude Cahun, also present in the exhibition. For Martin Bethenod, “The multiplication of the presence of I is contemporaneous with a time when the notion of the individual, the sovereign, autonomous subject, endowed with a fixed identity, was replaced by a conception of the individual as a network in perpetual metamorphosis or transformation, subjected to the forces and the social and cultural determinisms of race, gender, sexual orientations” The body is a construction, better, it is a game of construction. The body is fluid, like gender. It is old – dying, it is young. It becomes what is it. We could even say that it dances to the rhythm of its identities, its desires, its melancholy, its love, of life. The body is determined, it can be both created and released.

Dancing with myself at the Punta della Dogana, Venice, on until December 16th 2018.

*We have to own up, this was actually an anecdote told to us by the director of FIAC, Jennifer Flay, during the weekend of the opening of the exhibition.