NUMÉRO: What’s your background? What did you study?

TOBIAS KASPAR: After secondary school, I went straight to study art in Hamburg and Frankfurt. I like classics: Herman Melville’s novella Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street is one, it also explains to a certain degree my approach; I prefer not to, but then he (Bartleby) is also not leaving but somehow remains present. This book, other literature – for example, the German Romantic poet Friedrich Hölderlin –, but also the giant Barnett Newman painting [White Fire II, 1960] in the Kunstmuseum Basel, one of the oldest public collections in the world, remain everlasting influences.

How much did your background influence you?

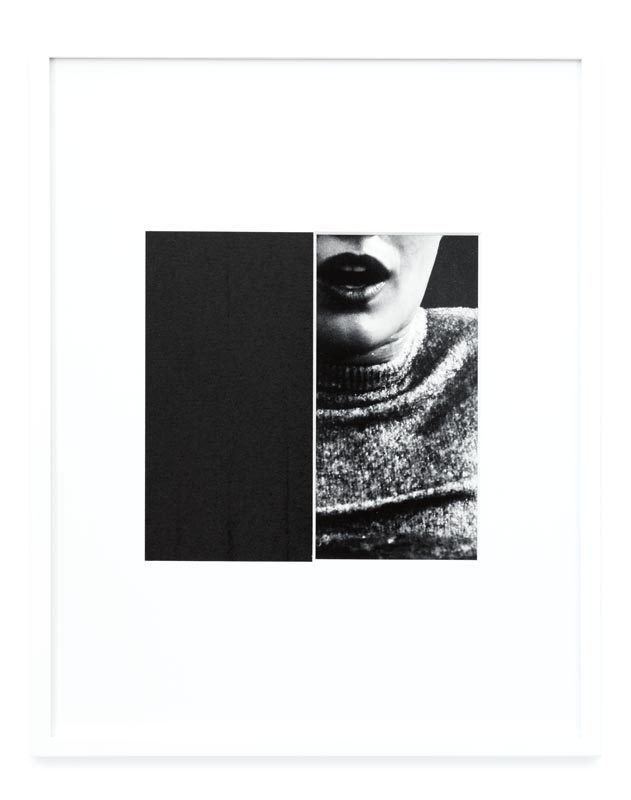

Recently I read I Am Not Sidney Poitier by Percival Everett. The book’s main character is called “Not Sidney,” which of course creates a grand confusion and many frustrations. Refusing who you are, what you represent – you can’t really escape it but you express a certain discomfort, unease and will for change. Already at school we learned about artists like Hannah Villiger or Cindy Sherman.

“I like dressing up, jumping into new roles. I also like to be able to change a signature style drastically.”

At what point did you decide you wanted to be an artist?

I never wanted to be anything else. When I grew up, art wasn’t linked to money as it is today. The artists I knew through my parents and the house I grew up in had nothing to do with money. In the 90s, everyone lived on a small budget. The fact that I grew up 500 m away from Art Basel always impresses everyone, but it really didn’t matter. It’s only now that everyone starts to expect you to buy an apartment and houses… It’s so sad. But on the other hand it pays my rent – like in the rest of the world, money is not distributed equally in the arts. Since I grew up in an artistic milieu, the art world never represented to me an escape zone from certain bourgeois patterns. It’s a “reflection zone” where we all can take a step back and look at the world through the glasses of art, since our globalized art incorporates just about everything and almost no free spaces are left to contemplate art which, for obvious reasons, plays an ever increasing role.

Do you remember your first encounter with art?

At home. And my godfather’s studio definitely left a lasting impression. He studied with Joseph Beuys in Dusseldorf, painted like Blinky Palermo, lived with a mattress on the floor in his studio – quite romantic in a way. Today he lives in Croatia on an island. Basel, as open as it is, can be simply too small, especially if you’re interested in practising a non-heteronormative lifestyle, no matter how liberal the city is. He was able to somehow explain to me or make me understand what Beuys wanted in general; the Kunstmuseum Basel has, among others in its collection, Beuys’s Feuerstätte II.

The title of your last show was The Category Is. Why did you choose this title, and how do you feel about categorization in general? And if you had to, how would you categorize your work?

I chose the title exactly for these reasons: I don’t like to be put in a box and I’m always trying to avoid doing it myself, which isn’t easy. We always want to pigeonhole and categorize everything. On the other hand, I like dressing up, jumping into new roles. I also like to be able to change a signature style drastically. The Category Is sounds almost like in a Vogueing night when a new category is being announced: “The category is: business women.”

Not only does your work incorporate fashion codes with relation to the industry and taste, you also run a fashion brand. What interests you in that field and how do you deconstruct or articulate the notions related to it?

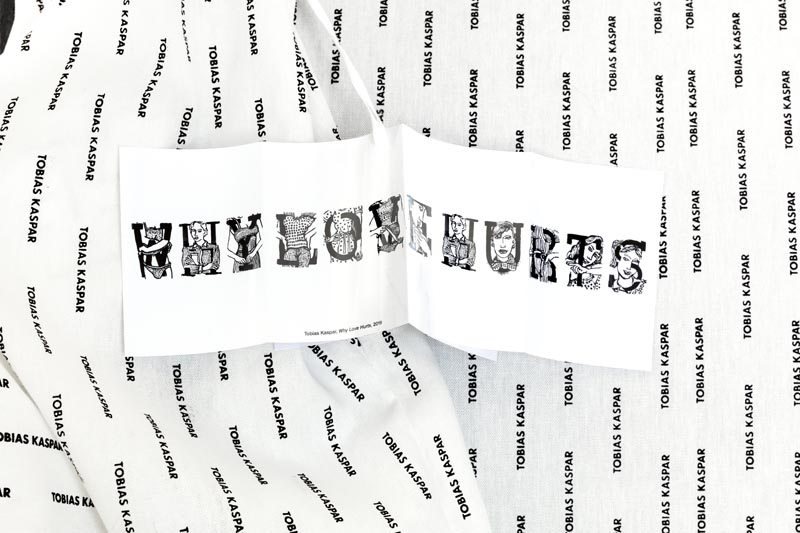

As an outlet for my clothes I have tobiaskaspar.com and a few concept stores that stock Tobias Kaspar. It’s becoming more and more a thing of its own, to a certain degree disconnected from my art output. I like that and it’s something I’d like to work on more. It started with a jeans line in 2012. I noticed that many artists get invited to “collaborate” with fashion brands but this meant having their painting printed on a T-shirt or some other kind of high-speed operation that didn’t look like actually working together in depth, something I enjoy. I therefore decided to initiate it from my side, almost like a preventive move before being approached by a major brand.

You’re also a publisher...

Exhibitions are not always the perfect medium, and in general I love books. Some projects or ideas are better on paper with a large print run. And that’s what the magazine PROVENCE is for – we do things other magazines can’t do.

Your name appeared as a logo in one of your recent shows which dealt with the notions of cars, branding, masculinity and capitalism. What was behind that?

I dislike cars, branding, masculinity and capitalism. The car is a prop which was built for a local theatre production of Bonnie & Clyde from which I appropriated it. For the exhibition I had a car cover tailored for it, branded with my name, and before that we brought the car to a Berlin shooting range and had it shot with several bullets – a re-enactment of the way Bonnie and Clyde got massacred. Repeating one’s name is also a way of forgetting.

You recently put on a solo show at the Kunsthalle Bern, but decided that your name would not appear on any of the exhibition’s posters or indeed in any of its promotional material or publicity. Why did you take that decision?

To challenge myself and the institution and to let visitors see an exhibition without knowing who produced it – although there were clues all over the place, and if one asked the information was not refused. Like the Kunsthalle’s homepage, our whole society is structured around names. A banal example: the programming of the Kunsthalle’s homepage does not allow it to list any new exhibition without entering an artist’s name. So we had to reprogram it.

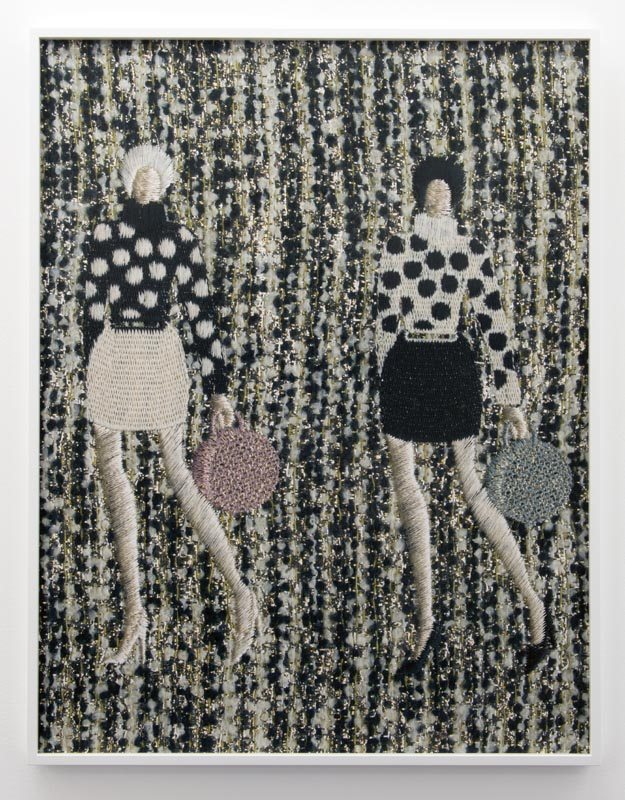

You’ve recently been working on a series called The Japan Collection. Can you explain why you decided to blow up these mini images?

By blowing them up to human scale, these 10 cm-tall figurative embroideries become uncanny ghost-like scenes of a bourgeois jet-set life or how this world wanted to see itself. These embroideries where made by a Swiss textile company for the Japanese market which opened itself up in the 70s to Western consumer goods.

“I don’t like to be put in a box and I’m always trying to avoid doing it myself, which isn’t easy. We always want to pigeonhole and categorize everything.”

What do you want to make people conscious of through your art?

I want people to stop whatever they are doing. Stop for good or at least rethink. I need to rethink too.

Do you feel you’re associated with a group or a movement?

As much as I like groups and would like to disappear into one, I always avoided any kind of movement or group mainly because, coming back to another question of yours, it’s about boxing, categorizing, creating borders and politics of in- and exclusion.

What’s your next project?

Vampire City, a large-scale exhibition to be shown at the earliest in spring 2020 in Zürich. In format Vampire City will be similar to The Street, which was shown in 2016 at the Cinecittà studios in Rome and was a hybrid between an exhibition, a runway show and a happening...