In 2018 at London’s Sadie Coles HQ, Urs Fischer showed a replica of Rodin’s sculpture The Kiss built in stiff white Plasticine. Unlike most works of sculpture, particularly those in fragile materials, visitors were invited to touch and even modify the work. The adjustments were initially modest and reverential – names or doodles scratched into the surface with a fingernail – but the sculpture soon underwent dramatic reconfigurations. The faces were remodelled, an arm ripped off. Reduced again to a raw material, the modelling clay started to migrate around the room, reborn on the walls, floor and window as new words and figures. A few visitors attempted to heal the embracing figures, sticking the arm back in place, smoothing things over, but there was no returning to the glossy perfection of the untouched work.

The entropy incarnated in Fischer’s mutable version of The Kiss finds an echo in the artist’s own interrogation of ideas and enthusiasms, which he pursues doggedly until they, too, disintegrate. A few years ago he was fascinated by cinema. “I used to watch up to three movies a day,” recalls the Swiss-born artist. Fischer eventually became so suffused in this flood of cinematic information that he hypersensitized himself to the formulaic nature of almost everything he watched. “It kind of dismantled itself,” he says. “Now I’m not so easily fooled.” In place of watching movies, Fischer has returned to drawing. He has two young daughters, and admits that “as a parent, evenings can be long. I work on my phone a lot – I make pretty elaborate drawings on it. I have a few hundred by now. There are some from life, but they’re mostly made up.” Fischer’s exhibitions tend to remain unfixed until the eleventh hour, but his current plan is for these drawings to be the foundation of his show at the Modern Institute during the Glasgow International Festival in April. The question on his mind is how to get them off the phone. Perhaps they could be reincarnated as silkscreen prints? Or maybe lithographs? “We’ll figure it out,” he says.

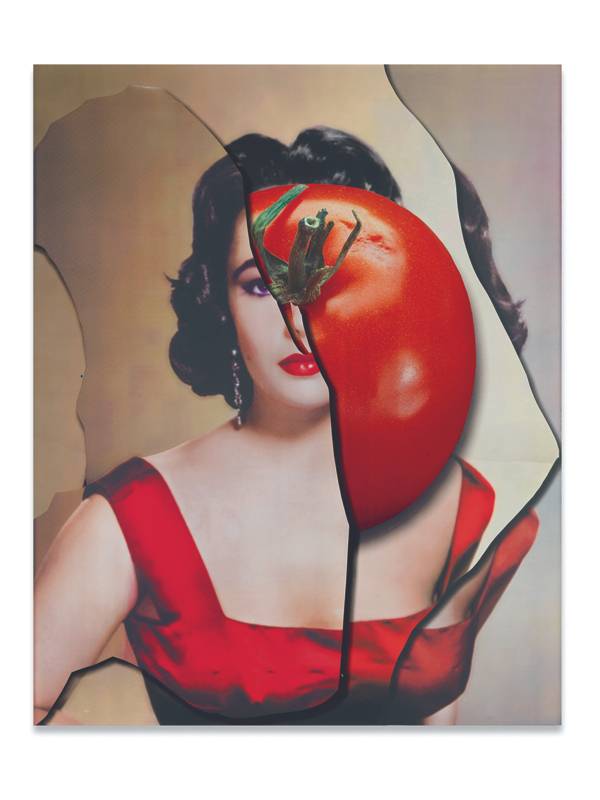

“Problem Painting” (2011), 360 x 270 x 2,5 cm. Collection Pinault.

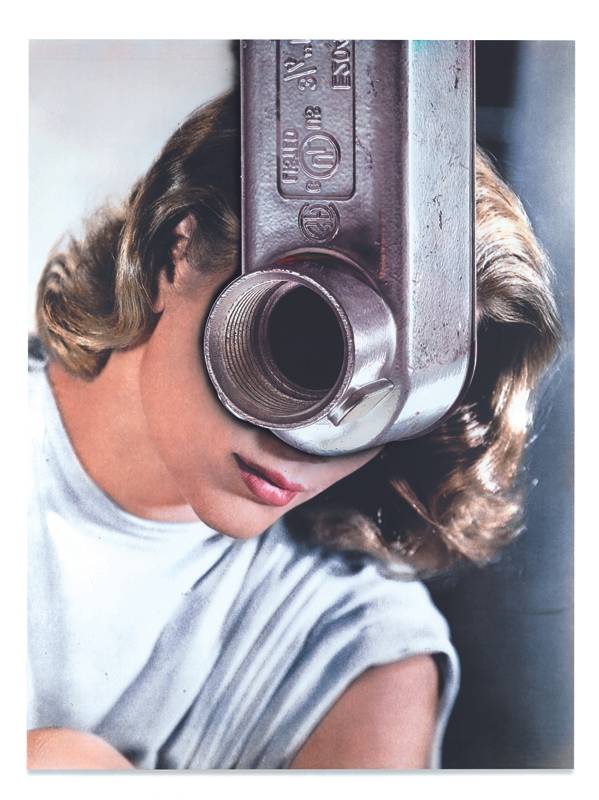

“I can’t believe you did this” (2016) 243,8 X 194,9 X 2,2 CM.

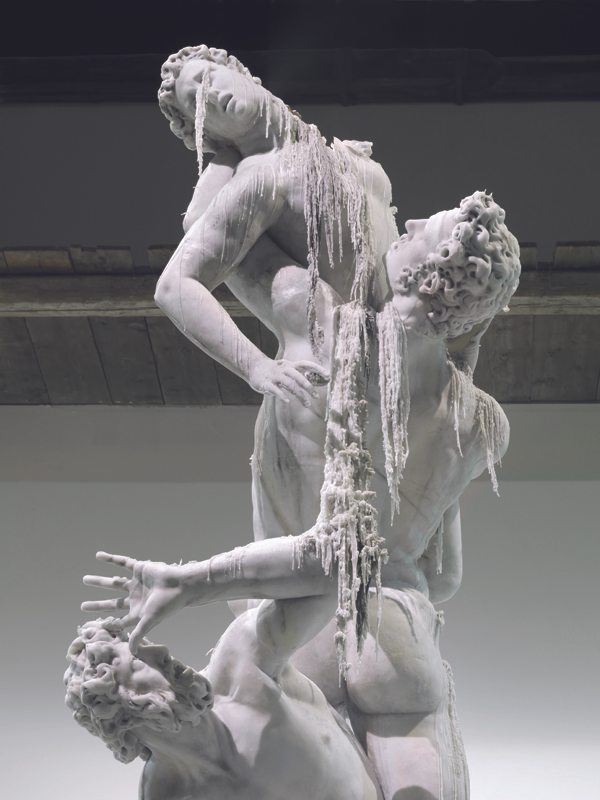

Now 46, and long a resident of New York, Fischer has delved into many intersecting worlds of making and unmaking. There’s been rebellious bravado: for You (2007) at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York, he notoriously excavated a 9 x 11 m hole, deeper than a standing man, into the gallery floor. With his childhood friend and sometime collaborator Scipio Schneider, he has wallpapered spaces with their own life-sized photographic images – a high-tech updating of the vainglorious 1:1 maps in Borges’s On Exactitude in Science. There have been many series of melting-candle sculptures, such as the life-sized nudes of What if the Phone Rings (2003) or a full-sized replica of Giambologna’s The Rape of the Sabine Women at Venice in 2011. Last year the Italian curator Francesco Bonami appeared in melting-wax form standing atop an open refrigerator in a Florentine piazza.

Though he has never shied from working with specialist fabricators and large studio teams, Fischer is in a new mood of handmaking. “Through working with a lot of help, you lose intimacy with the works,” he says, before suggesting that that’s not always a bad thing. Of the two other exhibitions that he’ll have later in 2018 one, at Sadie Coles HQ in London, will be “very hand made. I’m just trying to get more time for that – but that’s my interest.” The other, at Gagosian in New York, “is stuff I’ve worked on for about two years. A lot of it is very produced, machine made.” Two forces drive Fischer’s renewed interest in the hand as a tool. Once again his experience as a parent plays a role. “Before this project, I had my daughter’s preschool come to the studio. I made a whole Manhattan skyline out of cardboard and gave them a lot of paint.”

He relishes the memory of that messy abundance: “They had so much fun.” The other is YES, another exercise in abandon and amplitude, which Fischer started in 2011. Rather than paint, YES celebrates clay: 1,500 members of the public were invited to join Fischer in the creation of sculptures in advance of his show at MOCA Los Angeles in 2013. The artist has staged six subsequent iterations, including outings at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds, England, the DESTE Foundation on the island of Hydra in Greece, and in the public square skirting the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow. Bronze casts of some of the raw-clay works were later shown as Last Supper at the Gagosian galleries in New York. Unlike the Plasticine works, for which the loss of inhibition is used to destructive ends – “You start with an image and take the image apart: It’s not giving, it’s taking” – YES is about pure creativity. Fischer says he’s not interested in participation per se, but in how the non-judgmental, communal performance of sketchy creativity counterbalanced his tendency to check himself and employ art-historical filters. “My new-found love for a more intimate way of working comes from what I’ve learned from more communal projects where you just sit down and make something,” he explains. “With the clay works, people who feel blocked can just do it. They feel safe in this environment so they can let go.”

Fischer feels this pure joy in making to be at odds with the current art environment, which he feels is dominated by rules and limitations. “The artworld is one of the most conservative places that I know, in a way. What you should and shouldn’t do is very mapped out. Most people run along the same paths, all the while thinking they’re very free,” he says.

“I think the last generation of art that celebrated life was in Basquiat’s time.” It’s perhaps no coincidence that he mentions Basquiat: in common with that definitive New York artist, Fischer’s latest obsession is jazz. “It’s probably the coolest thing to come out of the last century,” he says. “Its influence has been crazy.” Together with artist/DJ/downtown legend Spencer Sweeney, Fischer runs a Sunday evening jazz space called Headz. Bringing art-making and live music together in the same place, Headz, says Fischer, is a “somewhat participatory thing: We don’t invite art people. We just have a lot of drawing materials. Some people walk in from the street.” While most artist performances now tend to take place in a sea of camera-phones (and most likely a self-mythologizing professional documentary set-up too), Headz exists only in the moment, well off the artworld radar: no website, no Instagram, and Fight Club-levels of non-discussion on social media. While awestruck by the musicians’ talent and adaptability, it is in jazz’s creative synergy that Fischer finds much to learn from. “These people just do magical things with each other – I’m always shocked,” he says. “A lot of artists, including myself, tend to over-think things.”