The last time I visited Xinyi Cheng’s atelier there hung, above a bench covered with books and clothes, a painting of two salukis swimming. Though I wasn’t particularly familiar with the behaviour of this type of dog in water, something about their haughty and relaxed attitude struck me as curious, to say the least. Seeing my reaction, Cheng pointed out, laughing, that their bodies were indeed unnaturally upright, as if levitating in the viscous liquid that they crossed with such unexpected grace. Immersed up to their necks, the dogs gave the impression of moving placidly through it, gazing into the distance, entirely oblivious to the atmosphere of chaos that would otherwise have permeated the canvas.

Xinyi Cheng tries to capture that which, in all her subjects, makes manifest their impenetrable character.

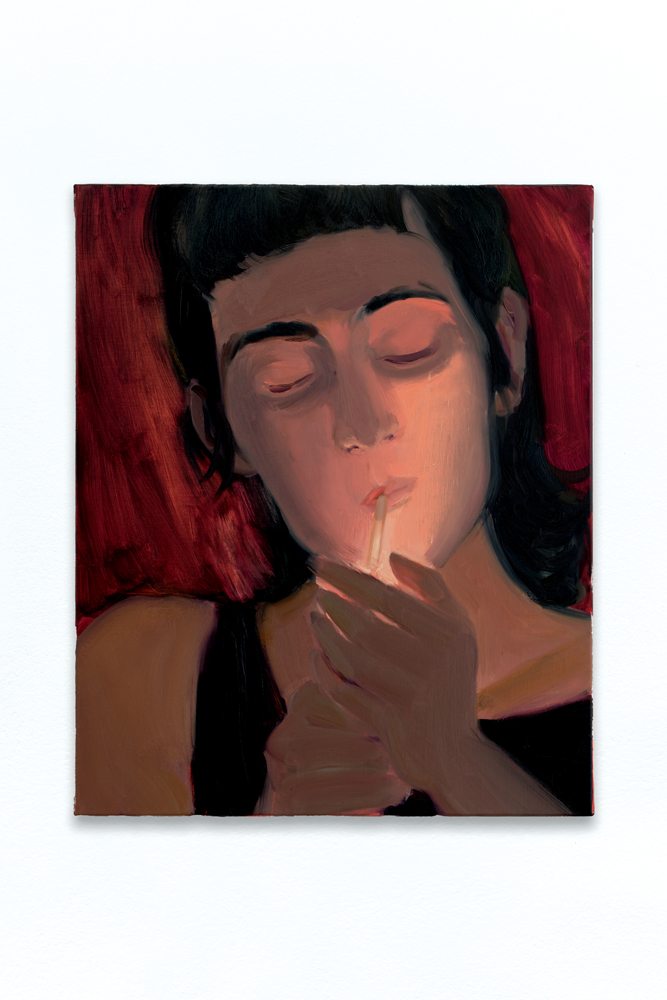

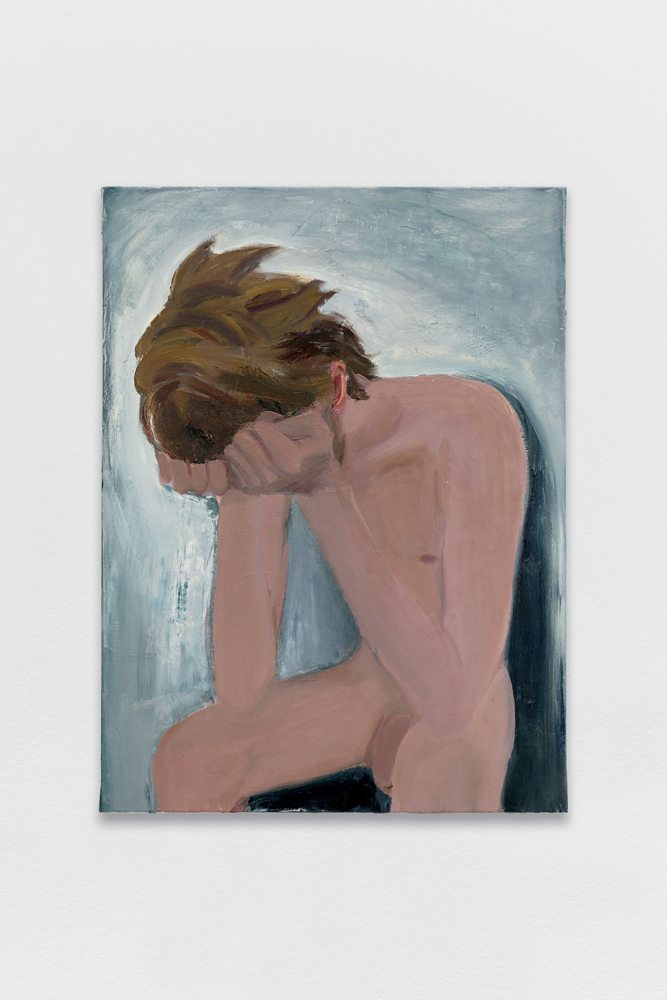

Although representations of animals are infrequent in this young painter’s work (a few dogs, more rarely cats and horses), they arouse the same troubling impression that permeates her human portraits. This impression is engendered by just a few details: the proximity of a flame to a face, for example, which can be seen in a series of recent paintings showing people lighting a cigarette, or the intimate connection established between bodies and objects by means of ambiguous gestures. But even more than what seems to unite things and living beings, it is sometimes what distances them (from the background of the canvas, from others, from a narrative thread that might pull them back) that holds the key to the strangeness emanating from her compositions. A flinching gaze, the bluish tint of pale skin, the excessive arch of a foot – it is when the framework of conventional perception starts to crack that Cheng’s painting comes into being. And in fact, even though she admits to painting only those close to her, Cheng doesn’t so much portray a community that has formed around her as she captures that which, in all her subjects, makes manifest their impenetrable character.

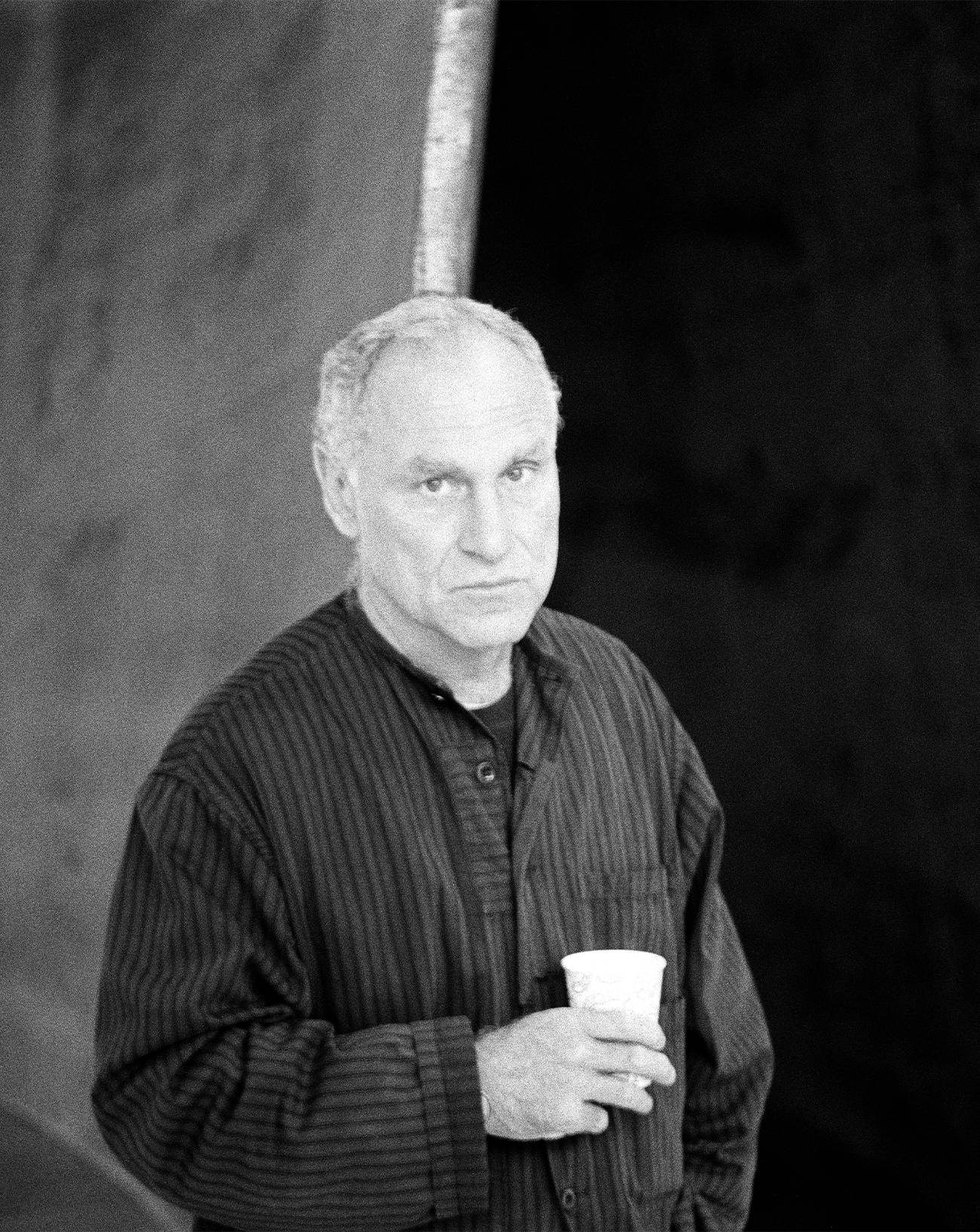

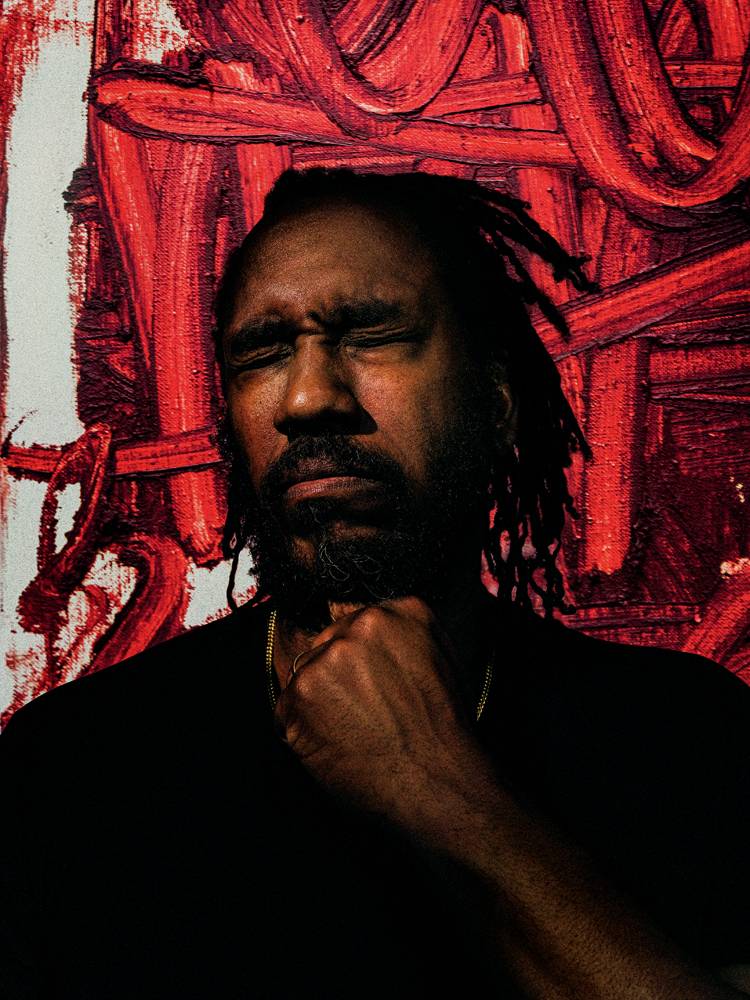

When preparing this text, I asked her to share with me some photographs of the people around her, most of whom she had met in the United States or in the Netherlands during her training as a painter, or later in Paris, where she settled a few years ago. In the file she sent, under the images of these bodies, the majority of which I had already seen on canvas, Xinyi had written a few words, specifying both the context of their meeting and what had made her choose these friends as models. As usual, nothing too personal: she sometimes emphasized a person’s physical particularities, such as the intense orange of Colombe’s hair, which contrasted perfectly with her emerald-green eyes, or the “Botticellian” contours of Josefin’s face. She insisted on the beauty of Jane, whom she had met in Paris, and also told me about the kindness of Jules, Stijn and Leqi – Leqi who had readily agreed to pose for her in her wedding dress. Several times her final comment was that such and such a person still remained a mystery to her.

If there is a dimension of memory to Cheng’s oeuvre, which follows the thread of her encounters and obsessions over the years, it transpires less through the reincarnation of a particular recollection than through the pursuit of an emotion associated with it. The way she uses paint as a material already carries a certain effect of withholding, and the treatment of light, perhaps inherited from her studies of classical sculpture in Beijing, creates different intensities on the surface of the canvas. Not only does light help structure the space by bringing out lines that catch the eye, it also, on occasion, seems to radiate from the models themselves or from the accessories that are placed near them. When this happens, the painting eschews all attempt at naturalism in favour of the expression of moods, accompanied by the assembly of tones and the incongruity of the poses, sometimes borrowed from an art-historical repertoire.

Xinyi Cheng's oeuvre transpires less through the reincarnation of a particular recollection than through the pursuit of an emotion associated with it.

This distortion of reality is due not only to the hybrid means used on the canvas to distance us from it; more generally, it is the faithful expression of Cheng’s perspective, which the painting seeks to account for accurately. This is not a quest for some form of objectivity or detachment, but, on the contrary, an attempt to own the distortion that feelings (of desire, love, friendship, but also of pain and frustration) generate, and to allow oneself to be overcome by what they alter and what they fix. In this respect, Cheng’s photographs – whose first aim is to capture these shared moments of life, but which are shown more autonomously in publications and exhibitions – provide an essential key to understanding her work.

In The Blower, a collection of shots published in 2018, we see a succession of rather austere still lifes, views of apartments that are either empty or inhabited by just a few shadows, and night photographs taken in the light of streetlamps or the stars, which accentuates their cinematographic character. Alternating with these are portraits of her friends at work, having a drink or doing their shopping, which warm up these uninhabited everyday places just enough to make them familiar environments.

The strangeness in Cheng’s oeuvre perhaps owes something to her regular life shifts from one culture to another. But, since biographical determinants never explain everything, we should not forget how much her work finds its impetus in a highly personal logic of perception. As much as the trace of relationships established with others, her work quivers with the trials and tribulations of the self, revealing its anxieties, confessing its solitude and the persistent embarrassment of wanting to know or say too much. One can sense an attitude that is both light and serious, a curious distance, perhaps a bit of a façade, that protects as much as it destabilizes. But no matter: this is certainly the path to hope, a way to keep moving forward.