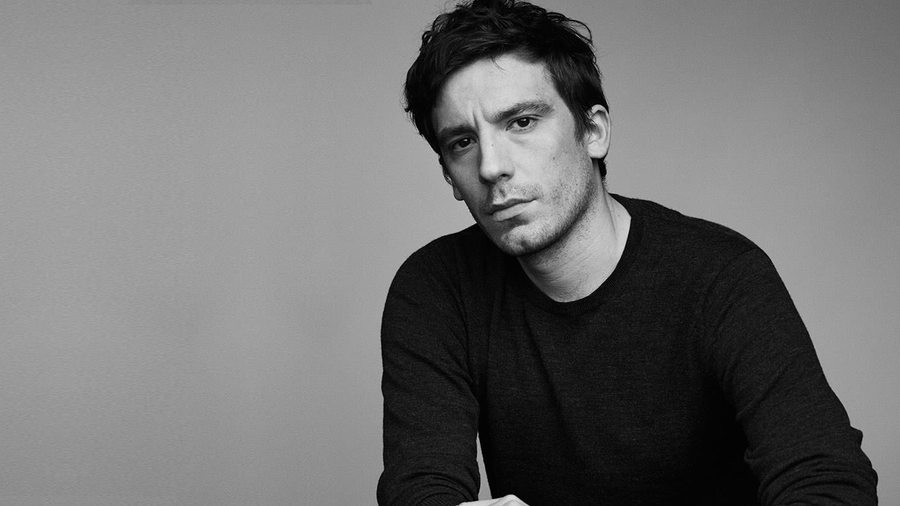

Named a year ago as artistic director of Paco Rabanne, Julien Dossena, previously at Balenciaga under Nicolas Ghesquière, has, in just a few collections, brought a breath of fresh air to the house. Between inspiration drawn from lingerie, sportswear and the metallic materials emblematic of the brand, creations by the always discreet Julien Dossena are a clever blend of genres and styles. As the first Paco Rabanne boutique opens in Paris on the rue Cambon, Julien Dossena confides to Numéro about the project and his own vision of the label.

Numéro: You’re reinventing the vision of Paco Rabanne with very contemporary runway shows, there’s no retro nostalgia here…

Julien Dossena: The Paco Rabanne aesthetic, based on the assembly of metallic and industrial elements, was well ahead of its time. But taken like that today and it would be perceived as retro. Since starting at the house, I’ve been asking myself how to re-transcribe that spirit of the brand into now. What set it apart was this sense of innovation. We wanted to take the past into account but in a different way, without going into the archives, and more by working with its values and philosophy. That’s what Chanel did in her day: break with nostalgia and move with the times, invent a relevant lifestyle.

Another hazard would be to fall into science fiction with an overly visionary and technical vocabulary.

Exactly. What’s interesting at Paco Rabanne is that the brand, in spite of its very conceptual guise, quickly moved into the mainstream culture of its time, into the movies, on television. It was worn by Amanda Lear, Jane Birkin, Françoise Hardy... There was an effortless aspect to it, a young woman in flat heels, and that’s how she wore it to go dancing at Castel. It was never weird or Lady Gaga outlandish, just a very easy style to assume. So we questioned how to preserve this balance between the radical and the effortless.

Since you started as head of Paco Rabanne, you’ve notably worked and adapted pieces of sportswear.

Sports clothes today are more high performance and innovative than ever. They’re ergonomic, enhanced with inserts positioned at exactly the right place to serve the needs of a body practicing whatever discipline. The idea wasn’t to reproduce these pieces but to draw inspiration from certain characteristics and use them in luxury garments. For example, nylon has been replaced by a coated silk: its finish, lightness, resistance and capacity to conserve heat are all very similar to the qualities of nylon. But to the touch, it’s clearly still silk.

Your spring-summer runway show was about a girl at a music festival…

I wanted to enrich our vocabulary by working on an aspect of the house that had yet to be exploited: craftsmanship, the hand-made. It evokes the opposite to a high performance or industrial garment, but is still part of the brand because Paco Rabanne was an haute couture house. It was the idea that a girl could re-work her dress, recycle certain elements. But without any sense of nostalgia: this grunge, eco or recycled aspect, almost Mad Max-like, is very contemporary. It was about evoking the girl who makes holes in her jeans more than the one who buys second hand clothes to look like a 1960s YSL model.

How do you deal with the conceptual aspect of the house of Paco Rabanne?

For the founder of the brand, clothes really were an artistic expression on the same level as painting or music. He was hanging out with Dali, Boulez, and wanted to be a part of the avant-garde. Obviously the industry is different today. To express this conceptual aspect, through visual communication for example, we worked out our corporate identity with an agency in London whose other clients include artistic bodies like the Tate Modern. Same thing for the boutique sound track: we worked on sonorous “layers” with synthetic bird song, like a sort of galactic spa. We operate by sliding the register subtly, all while remaining in the field of the fashion industry.

Is this same approach present in the conception of your first boutique on rue Cambon, Paris?

The boutique was designed by Belgian architects Kersten Geers and David Van Severen, who generally work on museum projects, or a project for a political space between Mexico and the United States. They also did the Belgian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale of 2008. For me it was about bringing this kind of person into our milieu, with their own specific constraints. It’s these sorts of diversions that interest me. For the interior of rue Cambon, they had the idea of two perforated metal boxes with modular walls, linked by a corridor lacquered entirely in beige. The effect is one of contrast between a noble industrial aspect and modernist bourgeois look. This first boutique is important in establishing our identity, and for getting to know our client better. It’s also provided a model that we can adapt according to country.

Paco Rabanne, 12, rue Cambon, Paris Ier.