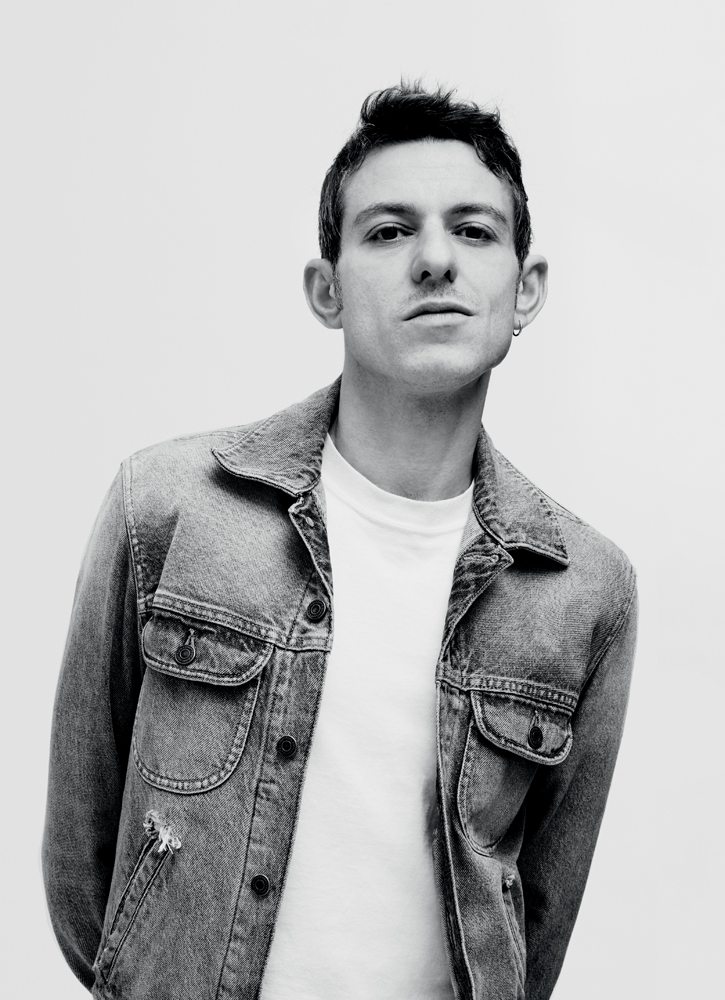

Numéro: How did fashion come into your life?

Nicolas di Felice : I come from a little village of under 100 people near Charleroi, in Belgium. When I was young, I didn’t have access to fashion images, it’s something I discovered through music and videoclips. I didn’t know there was a fashion business, I was more interested in musicians’ looks. It was a horizon that seemed to open for me in the Black Country, as they call that part of Belgium, because of the fine, dark layer of dust that the wind blows from the slag heaps...

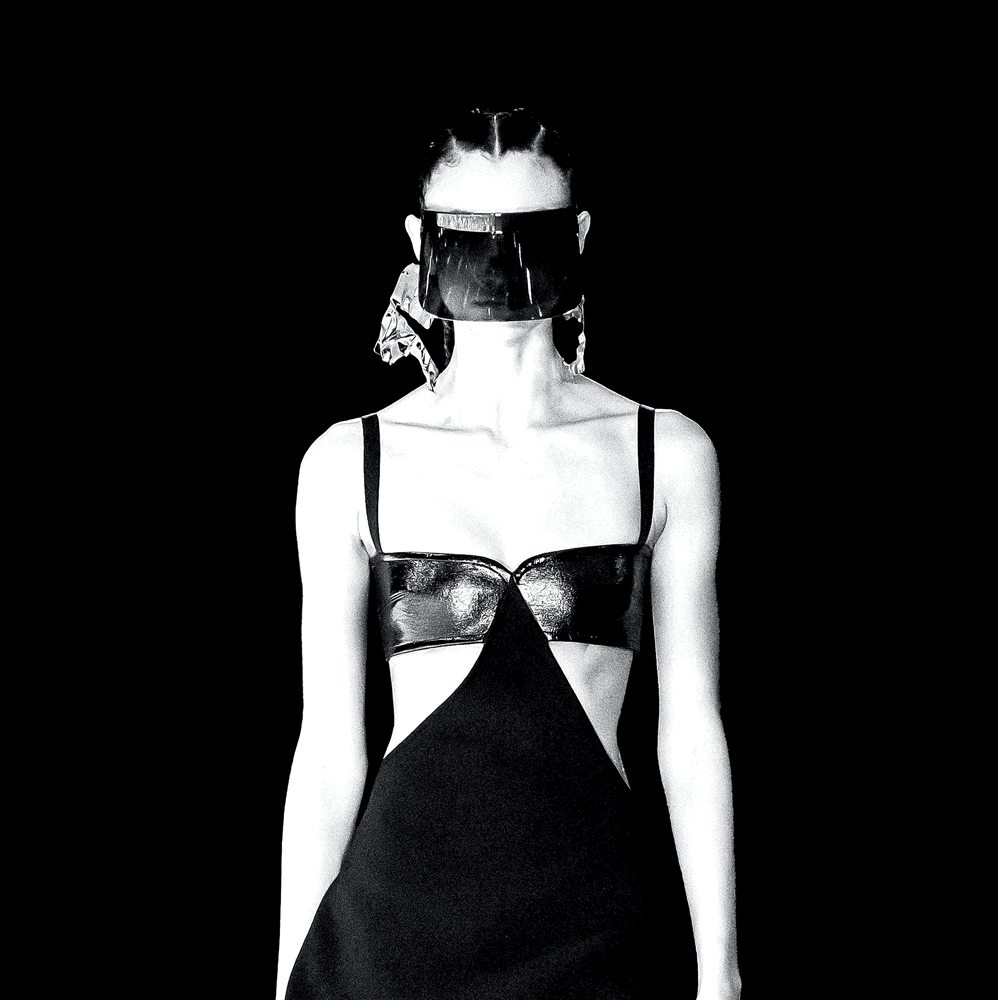

“That mountain of cans I showed looks like it might be diamonds when you first see it from afar. Obviously we’re going to use those same cans throughout the season for every show, because we’re trying to be as eco-responsible as possible, even with our vinyl.”

It sounds like the kind of landscape you find in the north of England.

Exactly, a post-industrial landscape. There are workers’ estates, little villages with low houses in brick next to disused factories with giant chimneys. The nightclubs are out in the countryside in the middle of nowhere. When I was a teenager, we had a Belgian version of Top of the Pops, a showcase for Belgian artists that was only broadcast in Wallonia. It was shot in a club called the Palladium where I started going when I was 14. It was all dance music and EDM back then, music that’s a bit prefabricated, so the main thing was to create a character around it, a form of dressing-up in many ways. So, after having been sent to Catholic schools, at around 16 or 17 I decided to study fashion, and enrolled at La Cambre.

You briefly worked with Raf Simons at Dior. Like you he’s Belgian, and much of his culture comes from music. Were he and the Antwerp fashion scene a reference for you?

I admire Raf a lot. I like it when a designer’s work reveals a personality and certain obsessions. André Courrèges followed his own path in a similar way. I also admire people like Rick Owens and Ann Demeulemeester, who’ve developed their own vocabulary. It’s something that’s typical of Belgian designers. When I started at La Cambre, Anthony Vaccarello was in the final year, and had already developed the fashion vocabulary he uses today. The school encourages a much more rock-and-roll, DIY spirit than the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, which suited me just fine.

“I try to extract Courrèges' essence without copying the past.”

For your autumn/winter-2022–23 Courrèges runway show, the audience had to walk through a sort of black box filled with night-club sounds, before arriving at a sparkling square parterre made from thousands of aluminium cans...

This contrast of black and white, this dark side, is totally part of my world. When I was young, I was obsessed with the idea of burying a diamond in the dust, and that was a little bit what was behind this runway set. I found an André Courrèges video from the 70s that showed models at a vehicle scrapyard. I really liked it, because usually the brand is associated with the image of a perfect white clinic. I live near the Buttes-Chaumont park in Paris, and I love it even more now that I know it was originally a rubbish dump. That mountain of cans I showed looks like it might be diamonds when you first see it from afar. Obviously we’re going to use those same cans throughout the season for every show, because we’re trying to be as eco-responsible as possible, even with our vinyl. Our rib knit and Milano jersey are also certificated as eco-responsible.

Courrèges défilé automne-hiver 2022-2023

You seem to be having fun with the Courrèges vocabulary, respecting its spirit without literally copying it.

The brand was historically described as “optimistic, lively, dynamic,” which for me doesn’t mean you have to do advertising campaigns with models jumping for joy. The whole approach has to be dynamic. I never copy the archives, but sometimes I reproduce the look of the materials that were used at the time. I try to make something with the same feeling but using the techniques and materials of today. I use double crepes, which are a lot less heavy than they used to be, and add a bit of wool jersey so that they seem more round, like Courrèges’s coats. The buttons look a bit like overstitching, which might seem strange, but all the archives are like that. I try to extract the essence without copying the past. I’m a bit of a technician, so for me it’s something I have to achieve through the choice of materials and the way of doing things.

“What I find inspiring are André Courrèges’s genius and romanticism. He took a leap into the unknown.”

Courrèges, who trained as an engineer, designed futuristic, sporty clothes that were meant for every-day wear. Do you identify with that “revolutionary” spirit?

What I find inspiring are his genius and his romanticism: when he founded his label, he took a leap into the unknown with the woman he loved. I’m more interested in the meaning of his work than the context of the 1960s and the drive for innovation, the enthusiasm for the future, that was part of what he did. I try to do something that has meaning for me in the same way things had meaning for him. Today is also a period of change. After two years of pandemic, my March runway show took place in a general feeling of liberation. Which meant that this parallel with the 60s seemed right. What I want is to dress people – it’s not about making anyone “dream,” but rather offering something in which everyone can find themselves.