November 2014 on YouTube: a video entitled Poppy Eats Cotton Candy gets the web buzzing. In front of a pastel-green backdrop, a girl with long platinum hair and a sequined pink top eats a stick of candyfloss. Once finished, she looks mischievously at the camera, sticks out her tongue and giggles. The screen fades to black. In barely a minute and a half, with neither captions nor explanations, YouTubers discovered a strange new fetish figure, who was back a few days later with a second clip entitled Thursdays Are So Boring: to a J-pop soundtrack by Kyary Pamyu Pamyu, she had her nails varnished by two people disguised in full body suits. Once again there was no dialogue and no information, mystery reigning supreme. Viewers had to wait almost two months before the peroxide blonde’s professional identity was revealed in a third video that had her looking into the camera and repeating “I’m Poppy. I’m Poppy. I’m Poppy,” for 10 minutes straight. Absurd, hypnotizing and disturbing, the clip went viral. That day, 7 January 2015, Poppy was officially born.

With her doll’s face, high girly voice and fake smile, Poppy is a “phenomenon” in the strict sense of the word (in its original Greek it means “that which appears”). Firstly because she emerged as an essentially visual apparition, virtual and volatile, as disembodied as she was elusive. Provided you had internet access she could be called up from anywhere, a pastel vision in soft lighting. But she was also a phenomenon in the more accepted sense of the word, springing into the limelight in a way that, while entirely symptomatic of our times, was utterly original. Freed from materialization or explicit intentions, her presence in the virtual world was entirely solipsistic and needed no justification.

As a good product of music industry, Poppy belongs to a generation of artists whose music is only one part of a global identity.

From the start she fascinated, attracting a community of fans, who, as though observing a strange phenomenon in science class, watched her talking to a plant or taking questions from a robot called Charlotte Quinn. Her rehearsed replies, all given with the same angelic expression in the same bright monotone, raised a disturbing question: in the end, wasn’t this bubble-gum girl even more artificial than Charlotte the robot? And who was behind all this? The truth is that the Poppy avatar was the creation of not one but two people: the first, who we see on the screen, is a certain Moriah Rose Pereira, born in Boston in 1995; the second is an American director and musician called Titanic Sinclair. Together they dreamt up these kooky videos in which Moriah always took on the starring role, ironically parodying today’s advertising, blogger and YouTuber trends, but also politics, culture, society and technology, and in doing so subverting a whole ecosystem with their cryptic soigné scenarios.

In July 2015, the project moved into another dimension when, under the pseudonym “That Poppy,” Pereira brought out her first song, Lowlife, which featured vacuous lyrics set to a very pop melody against reggae arrangements: “Baby, you’re the highlight of my lowlife / Take a shitty day and make it alright, yeah, alright.” Her first EP, Bubblebath, which came out shortly after, deployed the same artificial pop sweetness, with four bright tracks that would have been perfect for a children’s cartoon. It was then that Poppy began to make her first stage appearances, give her first interviews and slowly metamorphose into a flesh-and-blood human being.

Poppy uses the expression “post-genre” to describe her music.

As a multimedia – rather than media – figure, she incarnated a new form of impenetrable pop star, draped in an aura of mystery to the point of engendering a “Poppyism” cult in her fans. Some commentators, when attempting to analyse the symbolism in her videos, went so far as to label her a member of the Illuminati. A perfect product of the music industry version 2.0, Poppy belongs to a generation of artists whose music is just one facet of a global identity, a visual and virtual persona onto which we can all project our fantasies. Today, now that she has become a more conventional kind of star, Poppy has no regrets with respect to her online beginnings: she never identified as a true YouTuber, nor did she appear like one, her strange films being better read as a form of performance art. As for the character portrayed in these videos, she considers it part of herself: “She wasn’t so much a character who was external to me as an extension of what I was like when I was younger. Right now I’m an evolved version of that.”

Just as prolific musically as with her videos, Poppy has brought out four albums in as many years, covering everything from pop and electro to rock and dance. This wide artistic repertoire has progressively freed her from the facile stereotype of the pop bimbo, bringing her ever more fans but also growing attention from the music biz. Indeed her third album Am I a Girl? featured several prestigious collaborations, including a track with the producer Diplo and another with the Canadian singer Grimes, who shares Poppy’s passion for avatars. Poppy uses the expression “post-genre” to describe her music: “It means that I don’t identify with any genre in particular, because limiting yourself to just one genre is boring. The music I make is the music I like to listen to, and that changes.” Her new opus I Disagree is the perfect demonstration of that: the track Concrete, for example, unexpectedly but very successfully fuses metal, rock and K-pop in a mélange influenced by Queen, The Beach Boys and, most of all, Marilyn Manson. A major reference for Poppy, Manson began messaging her on Instagram in 2018 to show his support, and they’ve since become good friends: “He gives me a lot of good advice,” she confides. “He’s one of the last rock stars to be so influential in his own lifetime.”

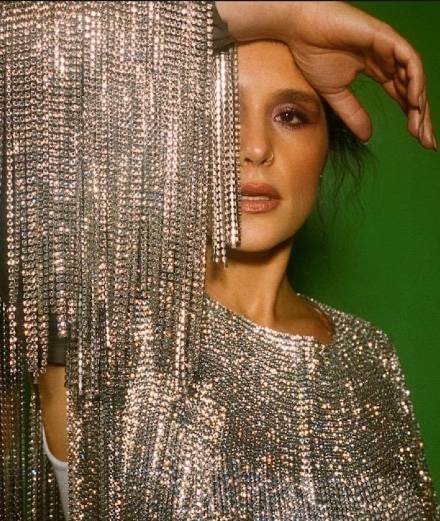

Following in Manson’s foot- steps, Poppy’s most recent album is far more sombre, right down to the cover, realized by the artist Jesse Draxler. Looking darkly at the lens, with black inscriptions around her eyes and mouth and a chain of spikes around her neck, she appears in-your-face and threatening. “I think we’re living in a very dark world, and the industry at the moment is pretty dark.” Out with the bubble-gum girl, in with the emancipated, punk Poppy, who last December split with Titanic Sinclair. When asked what she most disapproves of, she replies, without hesitation, “Corporations, authority, news... I don’t get people who blindly follow any old thing without asking questions or who are incapable of thinking for themselves.” The lyrics on I Disagree, which she considers the “most real I’ve ever writ- ten,” don’t beat about the bush either: in Bloodmoney, she claims to “know what it feels like to have my soul sucked out of my body” and “what it feels like to be dead,” while in Concrete she asks to be buried six feet deep, covered in concrete and turned into a street.

“I disagree with anyone who blindly follows anything without questioning it, as well as with people who are not able to think by themselves.”

Despite the fire within her, Poppy, who is now brunette, carries herself with an aristocratic elegance that is fed by the power of her enigma, the pride of a woman who will not be pinned down. Reacting to some of her recent videos, her fans are surpised to find her “more human than ever” or to see her “coming out of character.” All of which she finds amusing: “I think that everyone is always playing a role. Sure you’re transparent and sincere when you’re sitting in silence and the defences are down, but, the minute there’s a camera or a microphone in the room, whoever you are you put on mask.” Whether masked or unmasked, Poppy continues on her ambiguous, mesmerizing path through a new world in which the real and the virtual fuse little by little to become one and the same – a human figure above all.