Sometimes, when I think of Lili Reynaud-Dewar’s work, the Encyclopédie – France’s very first encyclopaedia, published between 1751 and 1772 – comes to mind, though her oeuvre has neither the exhaustiveness nor the academic rigour of that Enlightenment endeavour. Yet, for me, her work seems to overflow with words, voices and ideas, through her interest in literature, because writing is such an important part of her approach, and becauseof all the artistic and literary forebears she references and appropriates – Guillaume Dustan, Sun Ra, Josephine Baker, Kathy Acker, Jean Genet, and, of course, Pier Paolo Pasolini.

Words, voices, and ideas are also the basis of her teaching at Geneva’s HEAD (Haute École d’art et de design), where for more than ten years she ran a seminar entitled “Enseigner comme des adolescents-x-es” (“Teaching like teenagers”), which she held in her hotel room and which consisted in getting the group to read together, talk together, and explore, interpret, share, and sometimes even quarrel together. When she showed me what she was planning for her solo exhibition, Salut, je m’appelle Lili et nous sommes plusieurs (Hi, my name is Lili and there are several of us), which is being shown at Paris’s Palais de Tokyo this autumn, she told me it was unlikey anyone would manage to see, hear, and grasp all of it.

Featuring some 40 films, the exhibition, which explores themes that have long been present in Reynaud-Dewar’s work – domination, subversion, the interplay between the intimate and the political, teaching, and the transformation of cities and everyday lives by modernity –, deploys multiple language registers and formulations, stretches time, and above all asks the question: “Can we say everything, and how do we say it?”

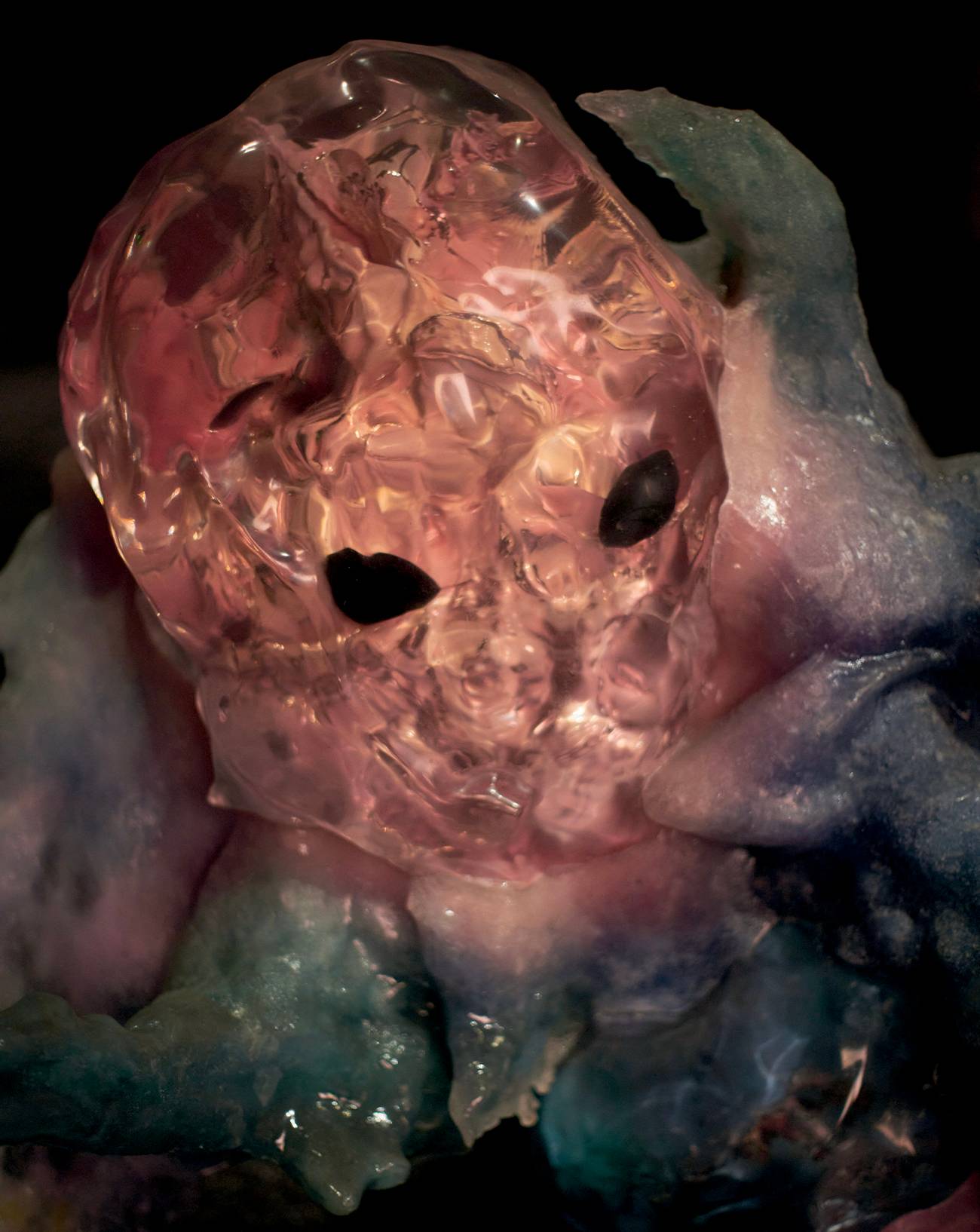

As part of this project, the artist asked 12 people who identified as men, and who only had in common the fact of being part of her immediate circle, to describe their lives through the prism of masculinity and private property. In each of the filmed interviews, which also took place in hotel rooms (cosily lit in pink, red, or orange), the montage gives the impression of a monologue, since Reynaud-Dewar has cut her questions. The cinematic and conversational techniques used here preclude overly-structured, polite talk; playing with conventional narrative beginnings and endings, they deliquesce and slant, as the digressions, omissions, and outpourings of speech underme the overly normative rhetoric of masculinity. As they recount very different, though never anodyne, personal stories and journeys – topics include AIDS, gender transition, addiction, chosen communities, discrimination, and sex and sex work – the interviewees unveil glimpses of events and socio-political crises unfolding beyond the camera frame. Together, these 12 interviews create a sample or portrait of a time and space rendered common by the narratives of those who inhabit it.

So where is Lili? Shown together in this way, perhaps these interviews also paint a portrait of the artist herself, based on the people who surround her and with whom she connects – as when she writes “I am Lili and there are several of us,” the “I” maintains a close and ambiguous relationship with the “us.” The interviews tell us something about the relationship, affect, and trust that must operate between two people to enable an exchange to come forth, as well as about how best to nurture the confession that is recorded, about what is cut and what is allowed to remain and to resonate in public. In a 1994 work, the artist Lutz Bacher also interviewed those close to her, asking them the question: “Do you love me?”1 Even if Reynaud-Dewar eschews asking her interviewees this question, love is perhaps also part of the equation. These videos are intended to be watched in beds built specially for the occasion, since the hotel rooms in which they were shot have been faithfully reproduced, so that the cinematic scenery spills over into reality. With this device, the artist somehow thwarts the slow disappearance of small, family-run hotels in Paris, at a moment when cities and the tourist industry are evolving under the often relentless processes of gentrification.

During an earlier conversation, we touched on the idea of “gossip,” a theme that Reynaud-Dewar already explored in the installation that won her the Marcel Duchamp Prize,2 a work featuring written biographical interviews with 24 actors, each of whom re-enacted the moments leading up to Pasolini’s assassination. The actors evoked stories of love, conflict, and working conditions in the art world – in other words, topics typically discussed at parties, in cafés, or even in hotel rooms, far from official channels. At the time, we discussed the research that Ramaya Tegegne – an artist, cultural organizer, and close collaborator of Reynaud-Dewar’s – was undertaking into this idea of “gossip” and the importance of oral history, of “rumours,” and the “grapevine” as political tools that allow the anecdote to find its place within larger systemic apparatuses. Some artists have incorporated gossip as a creative, discursive medium, like Dodie Bellamy for instance, one of the most celebrated authors of San Francisco’s experimental late-1970s New Narrative literary movement, who wrote in 2006 that “gossip, as a labour of disenfranchised subjectivity, feels rich.”3

In her book Video Green (2004), the author Chris Kraus, who is also close to New Narrative, discusses a creative writing course she taught in Los Angeles about keeping a diary. She observes that diary writing, an exacerbated, literary form of “gossip,” is an undervalued practice, one that is considered too tempestuous or banal to be capable of producing thoughtful, fixed, and prestigious prose. As a result, her course mainly attracted young artists who had given up trying to excel within the institution and yet seemed to be those most aware of its paradoxes and flaws. For the past two years, Reynaud-Dewar has been keeping a diary, one that can hardly be described as “intimate,” given that it is on public display on the walls of the exhibition, an exhibition whose preparation – among other events – it chronicles. This gesture sets her in a tradition of “diary” artists, such as Adrian Piper, Derek Jarman, and Lee Lozano, who, although they each embrace very different forms, ask themselves similar questions at the time of the writing, and particularly on publication: “How do you amplify what is usually whispered? What consideration should we give to the people quoted? What do we say and what do we hush up?”

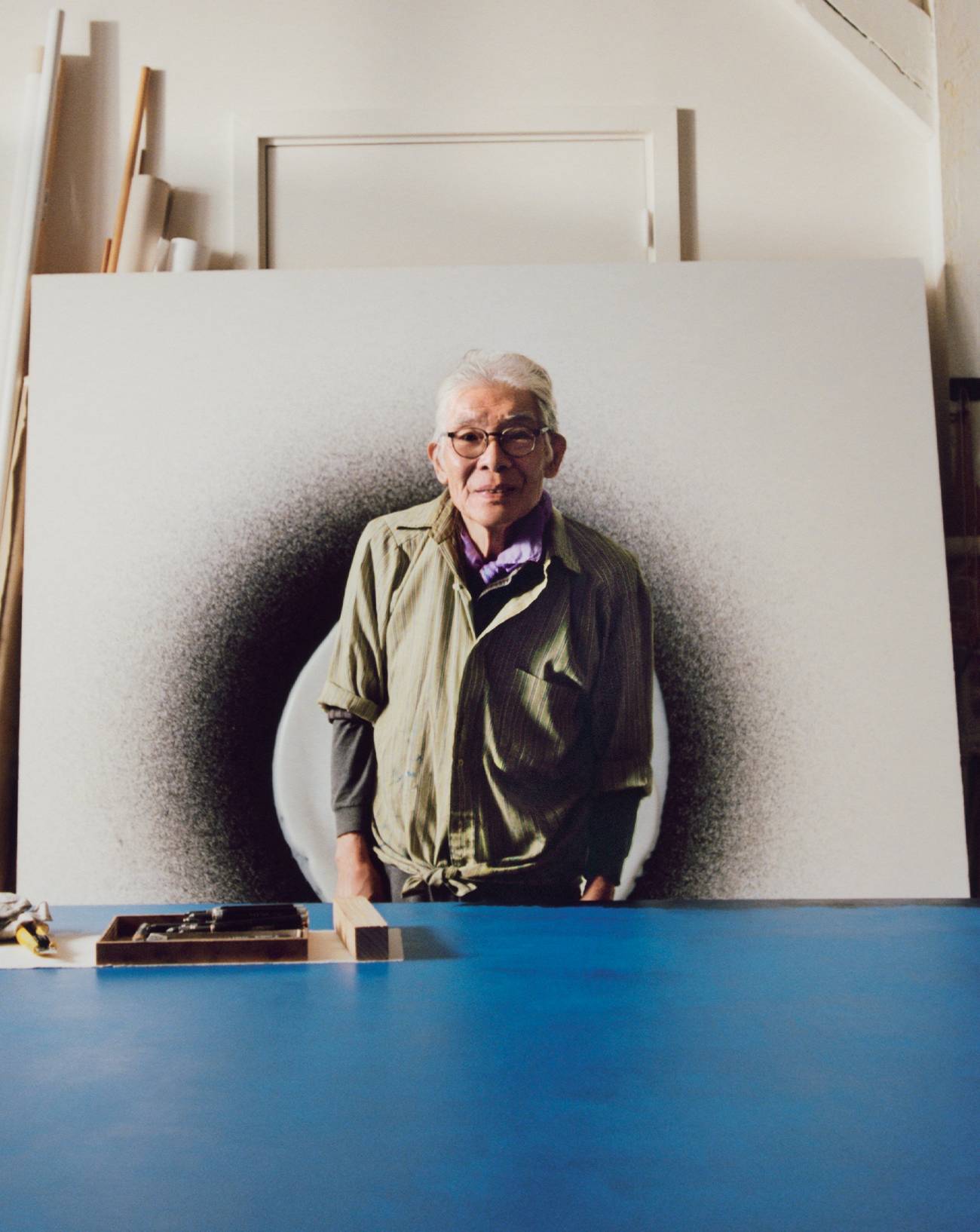

Inventing a new language based on gestures rather than on the spoken word, Reynaud-Dewar dances in an empty Palais de Tokyo,4 elegantly undulating alongside works by her contemporaries, exploring the spaces that we don’t usually see, with all the nonchalance, grace, and vulnerability of a body that sidesteps the habitual ways of moving through the institution. Another part of the exhibition, which is free to enter, allows visitors to watch all the episodes of Gruppo Petrolio, a kind of collective filmed survey of Pasolini’s landmark posthumous novel Petrolio.

In some ways akin to the Encyclopédie, Gruppo Petrolio is a collaborative work between Reynaud-Dewar and her students that deals with all the major themes in Pasolini’s book: the oil industry and socio-political conflicts, but also, as in her interviews, masculinity and property, or, as in her diary, the creative process and the possible subterfuges that allow us to allude to or to encrypt that which others may prefer to keep secret. Whether she is dancing in silence, speaking through important historical figures or through books that she has reappropriated, or handing someone the microphone, Reynaud-Dewar’s oeuvre spills over with declarations, narratives, and pronouns, and prompts the movement of language – language that is potentially sharp, ironic, choreographed, stammering, or filled with friction – as a tool of emancipation and empowerment.

Lili Reynaud-Dewar, "Salut, je m'appelle Lili et nous sommes plusieurs", from October 19, 2023 to January 7, 2024 at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris 16e.

1. First shown in France in 2022 at Paris’s Treize gallery in an exhibition of the same name curated by Julien Laugier. 2. Rome, 1er et 2 novembre 1975 (2019–21), first shown as part of the 21st Prix Marcel-Duchamp at the Centre Georges-Pompidou in the autumn of 2021. 3. Dodie Bellamy, Academonia (Krupskaya Books, 2006). 4. An artistic approach she has used for the past ten years or so, and which she repeats almost every time she is invited to exhibit in an art centre or museum. For Salut, je m’appelle Lili et nous sommes plusieurs, she is showing a new series of danced videos made during exhibitions held over the past two years at Paris’s Palais de Tokyo.