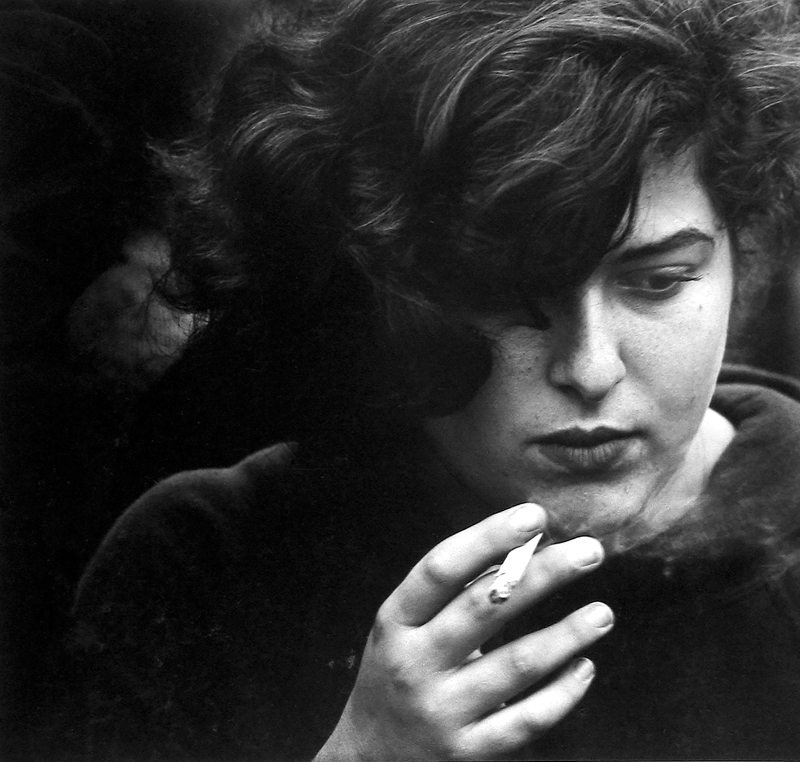

Psychology through photography? These three words might sum up the work of Dave Heath (born Philadelphia 1931, died Toronto 2016), a photographer hitherto forgotten in the short history of the medium. But his sumptuous black-and-white images remain, as does A Dialogue with Solitude, a book first published in 1965 (and reissued in 2000), and which is as sad as its title. It’s impossible to classify: a simple photo story for some, or a romantic language à la W. Eugene Smith – one of Heath’s references – for others. Heath’s vision of the human condition in the book is very dark. It explores individual solitude in ten sequences that are intercut with quotations – from T.S. Eliot, Robert Louis Stevenson, Rainer Maria Rilke, Hermann Hesse, among others – that range from military life (he was a G.I.) and youth alienation to the family and sexual relations… “These images follow a progression from lassitude to despair via anger, suffering, and, in the last few photos, the happiness and jubilation of a shared experience,” he wrote. In the book, time is suspended, an unprecedented exploration of the human psyche that was the result of a decade of experiments and trial and error. “I am soaked through by solitude. It’s marked my entire life. I did ten years of therapy trying to extricate myself from the trap in which I found myself. I think it all goes back to losing my mother, that psychological trauma. I created this work in an attempt to go beyond mourning, but instead of liberating me it pushed me deeper in.”

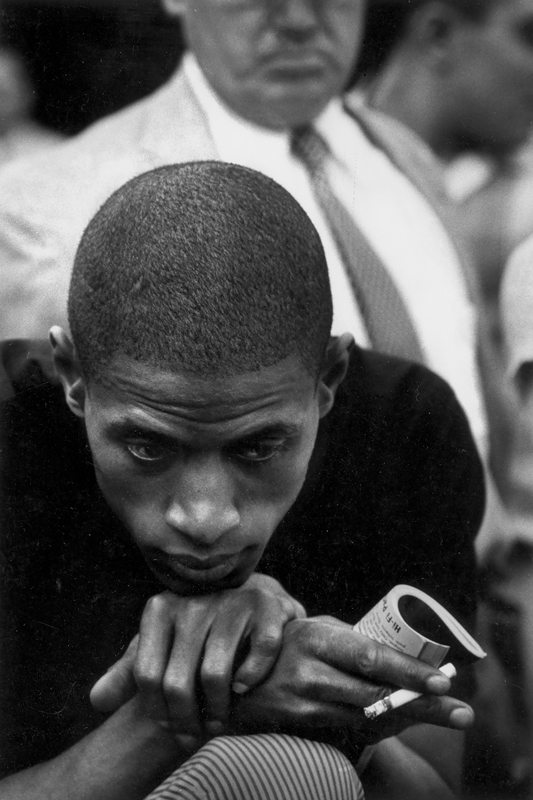

In 1952, he was drafted as a gunner in Korea, where he shot not just the enemy but also his first “interior landscapes,” as he called them, photos of his fellow soldiers in intimate moments, absorbed in their thoughts...

Abandoned at the age of four, Heath spent his childhood in orphanages and foster homes. At 15, a reportage by Ralph Crane in Life magazine, Bad Boy’s Story, had the effect of a shock. “I immediately recognized myself in the

story and also recognized photography as my means of expression.” He studied at a South Philadelphia technical college, before becoming a photographer’s assistant and working in the photo lab at a drugstore. Waiting tables got him the cash for a Rolleiflex, and he continued collecting essays on photography and the best shoots in Life. In 1952, aged 21, he was drafted as a gunner in Korea, where he shot not just the enemy but also his first “interior landscapes,” as he called them, photos of his fellow soldiers in intimate moments, absorbed in their thoughts. It was an attempt to seize “the vulnerability of a conscience turned in on itself.”

"I do photography the same way a poet writes a verse."

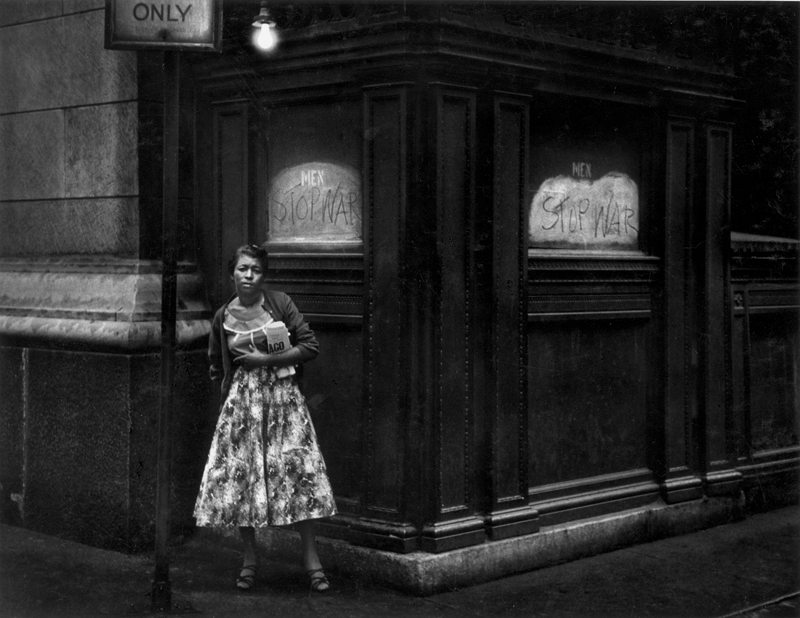

Back on civvy street, he began documenting urban life in Philadelphia, Chicago and New York, where he moved in 1957. “My photos are not about the city but are born of the city. The modern city as a stage, passers-by as actors who aren’t in a play but are the play themselves… Baudelaire talks of the stroller, but the goal is to give this crowd a soul. I do photography the same way a poet writes a verse. If it’s a good verse it might lead to a poem or appear in another work and complete a stanza. In the same way, as part of a sequence, a photograph functions in relation to others.” Heath’s was street photography, and yet he isolated people from the crowd, capturing a host of solitudes that he’d rush back to print in his dark room, as if he wanted to find the family and happy childhood he’d never had. A form of psychotherapy through photography.

All quotes taken from the book Extempore, long interview realized by Michael Torosian, ed. Lumiere Press (1988), reproduced in the exhibition catalogue Dialogues with Solitudes, coedition Le Bal/Steidl.

Dialogues with Solitudes, until 23 December, Le Bal, Paris.