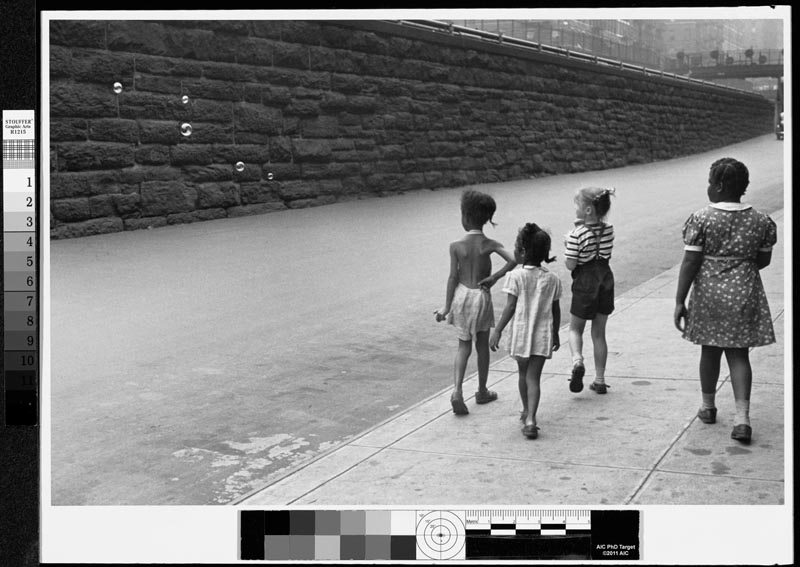

Out on the streets of New York, Helen Levitt caught the reckless kids in black and white, their drawings on walls and the women who watched them out of windows. Funny, incongruous, vibrant and resolutely human, these scenes, put next to one another make up her pictorial oeuvre: a genuine witnessing of the urban effervescence before people had television sets. It has been ten years now since she passed away, and Les Rencontres d’Arles is looking back through 130 original clichés, at her career and the evolution of this incredible artist, who went from photographing the streets to experimenting with colour and filmmaking.

Born in Brooklyn in the state of New York, Helen Levitt (1913-2009) quit school to become a commercial photographer which taught her all the techniques of analogue photography. Fascinated by the documentary photographer Eugène Atget, movies by Cocteau and Jean Vigo, she was also strongly influenced by surrealism. While she was teaching art to children in the mid-30s, she plunged herself into photographing life on the streets, intrigued by the scribbles they drew on the ground using chalk. The children and her imagination would become the prisoners of her Leica 35mm. Back then, New York would suffocate during the summer months. Everyone escaped their buildings looking for refreshment. This summer emulation fuelled her interest for urban photography.

Emotion remains the cornerstone of her work: a melting pot where poverty is blatantly obvious

Artist-photographer and so much more than just a simple visual reporter, Helen Levitt escaped this systematic division: she fixed her sights on American society and reflected its intimacy in the midst of the Second World War. Emotion remains the cornerstone of her work: a melting pot where poverty is blatantly obvious. To preserve the sincerity of her shots, she hid her camera under her coat and would drastically reframe her photos, each time discarding anyone who looked directly at her lens. From this bubbling diaspora we retain the resolutely organic urban scenes described by the New York Times as “ephemeral moments of lyricism and mystery”. Quickly recognised, her photos were published in magazines (Fortune in 1939) and various books. They were the object of numerous exhibitions including the inauguration of the photography department at MoMA in 1939.

Encounters with two of the biggest photographers of the 20th century galvanised her work. Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans provoked in her an all-consuming passion for the photographic medium. The latter fell in love with her photos of kids playing in the street and offered to accompany her in the New York underground where she ended up taking - incognito - her famous series Subway Portraits. He taught her how to play poker and introduced her to his friends. Through him she met the writer James Agee and director Janice Loeb with whom she made In the Street, a short film about the life of Afro-American children on the Upper East Side. Gradually Helen Levitt ended up working alongside the director Luis Buñuel who employed her as an editor on his propaganda films.

In 1959, Helen Levitt was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship for her research into colour photography. She abandoned black and white and when the grant was renewed the following year, she went back to the streets she loved so much, catching the brilliance of New Yorkers. According a new vitality to her iconographic spontaneity, the use of colour stimulated Helen Levitt and her shots were published in numerous magazines and papers including Harper's Bazaar, The Times, and the New York Post. In the early 1970s she was burgled and lost all of her undeveloped colour negatives… But it didn’t stop her taking photos, in fact it made her more determined than ever and she compensated by working even harder. Her hard labour was recompensed. In 1974, MoMA organised one of the first exhibitions of colour photography, presenting, in the form of a slideshow, an oeuvre of astonishing modernity by a certain Helen Levitt.

To be discovered at the Rencontres d'Arles in the Espace Van Gogh until September 22nd 2019.