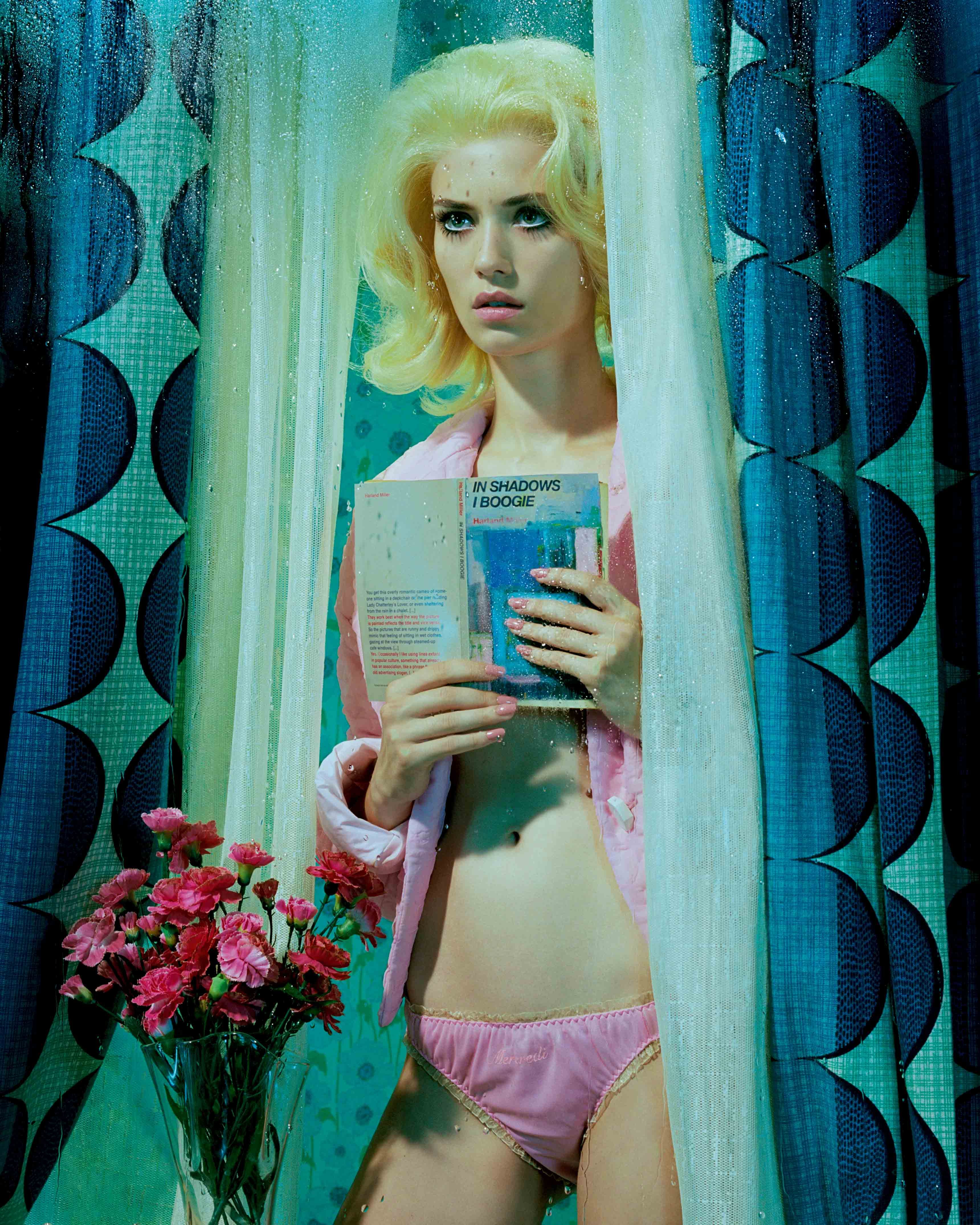

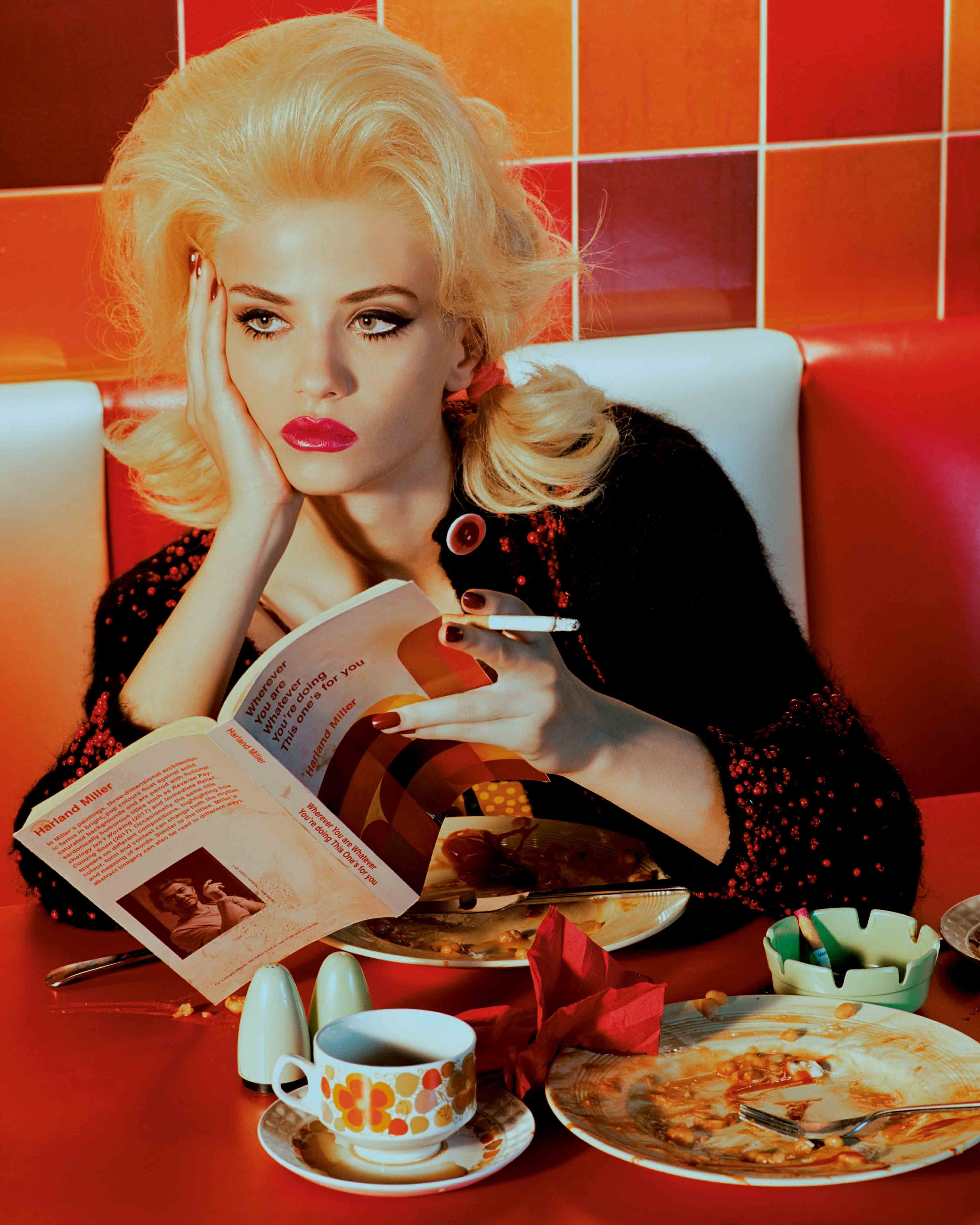

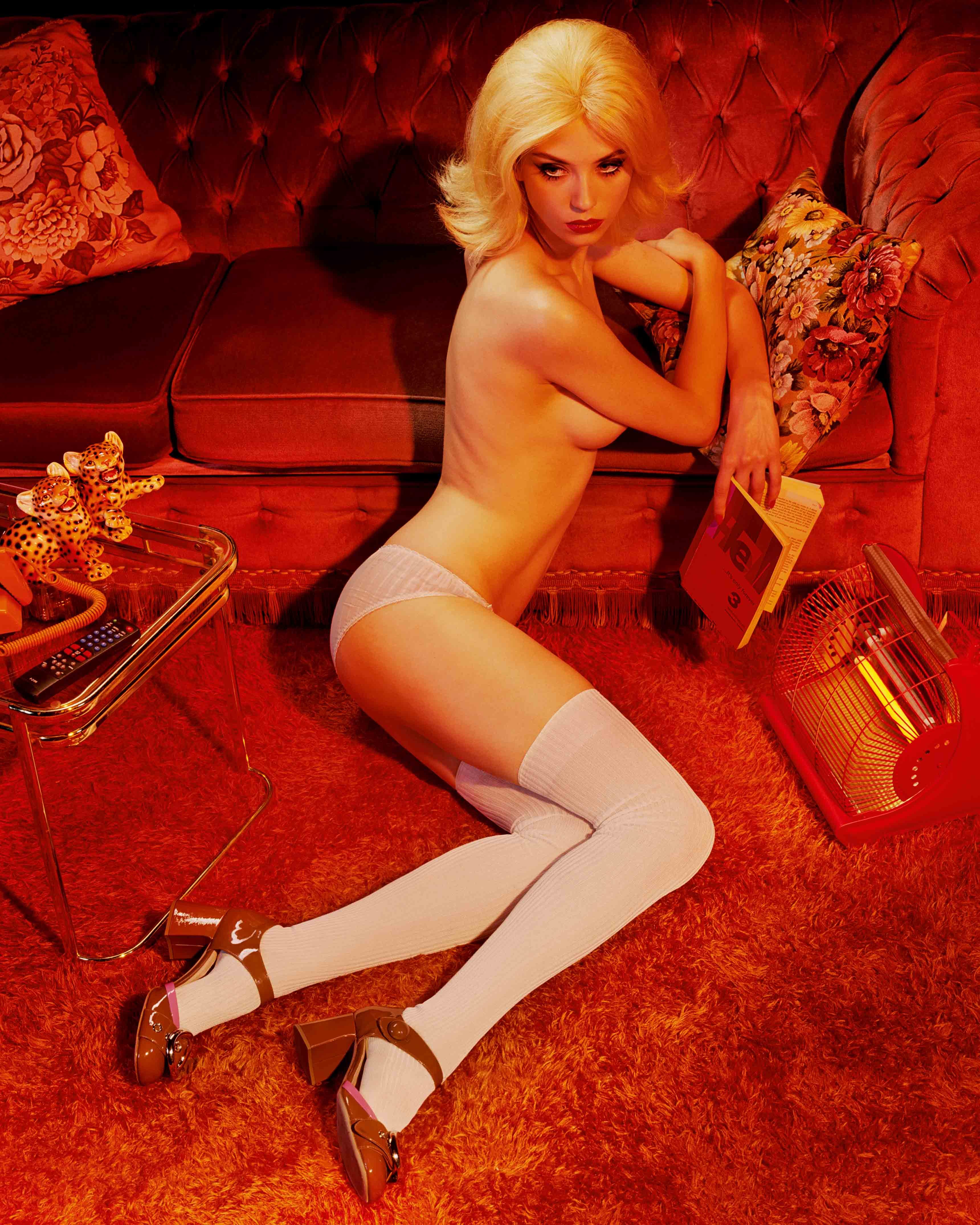

Is she enjoying Thought After Filthy Thought, that beautiful girl on the bare mattress who was photographed for Numéro Art by Miles Aldridge? She seems lost in reverie (or perhaps in sexual fantasy), but it’s not the literary merit or provocative themes of the book she’s holding that had anything to do with it. For behind the grubby cover with its blue-pink abstract artwork lies neither text nor tale: just like Reverse Psychology Isn’t Working or Immediate Relief... Coming Soon, it’s not a real book but an artwork by Harland Miller, a book-like painting repurposed by Aldridge as a painting-like book.

Inspired by the Op-Art-style cover designs of psychology and social-science books of the 1960s and 70s, the original paintings range from 1 to 3 metres in height. Three key ingredients went into their alchemy: the sardonic humour of the titles, the satisfyingly balanced cover graphics (created in consultation with a retired book designer in upstate New York), and the painterly execution with which Miller evokes a palimpsest of use, wear and water stains. “I think people relate to the work, if they relate to it at all, on a deep personal level,” says Miller. “When I used to do abstract work, I’d have people writing to me asking what it meant. Now I have people writing to tell me what it means to them.” Miller’s first painted book covers borrowed graphics from tatty pulp paperbacks of the kind he’d read as a kid growing up in York. After leaving Chelsea College of Art with an MA in 1988, he spent years in bohemian precarity amongst the demi-monde of Berlin, New York and Paris. Second-hand books were a cheap diversion. When he stumbled on a box of old Penguin paperbacks outside an English-language bookshop near Notre-Dame, Miller began subjecting the covers to irreverent reinventions, with retitlings such as Ernest Hemingway’s I’m So Fucking Hard and D.H. Lawrence’s Dirty Northern Bastard.

Aldridge – son of artist, illustrator and sometime Penguin Books designer Alan Aldridge – used Miller’s London studio for a music video in the 1990s, and the pair have been friends ever since. Looking over the proofs, Miller notes the satisfying symmetry of Aldridge’s converting his paintings into actual covers. The shoot’s setting is drawn in part from the British New Wave: “Miles is really steeped in all that cinema of the 1950s and 60s – Tiger Bay, The L-Shaped Room, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning,” says Miller. The cafés and working men’s clubs are locations the artist relates to, as is the experience of sitting in them alone, escaping into a parallel paperback reality.