It was around 10.00 am, and we were wandering through Recoleta Cemetery before the arrival of the hordes of tourists who come to take pictures of Eva Perón’s tomb. Winter was ending in the southern hemisphere, and the weather was delightfully crisp and sunny. In a dark pathway, we ran into a worker cementing a tombstone. “This one is for me,” he said, “if Macri stays in power. Ciao!” The tone had been set. The Argentina we’d arrived in was once again in the grip of a severe currency crisis, and was slowly drifting towards its umpteenth chaos. For better or for worse, Argentines are known for a resilience and a pride that allows them to move mountains, even in times of crisis.

“The only stable thing we have in this country is a 91-yearold TV presenter,” said, half jokingly, Lolo and Lauti, an artist duo with whom we shared a café con leche and medialunas. They’ve been working together since 2011, mostly in video and performance art. In 2015, with Violeta Mansilla, they founded UV Estudios, a gallery-cumproject space in the up-and-coming neighbourhood of Villa Crespo. They also started Perfuch, a performanceart festival which every year brings together over 100 artists, and which also redefined performance as an artistic practice in its own right – a way of escaping the domination of experimental theatre (a major discipline in Buenos Aires). During our conversation, we mentioned how everything seems very dynamic and buzzing in the city. “Yes, but it’s not easy to get funding or institutional attention. We may have made the cover of the national newspaper La Nación, but we’re still poor!”

The artist Nahuel Vecino.

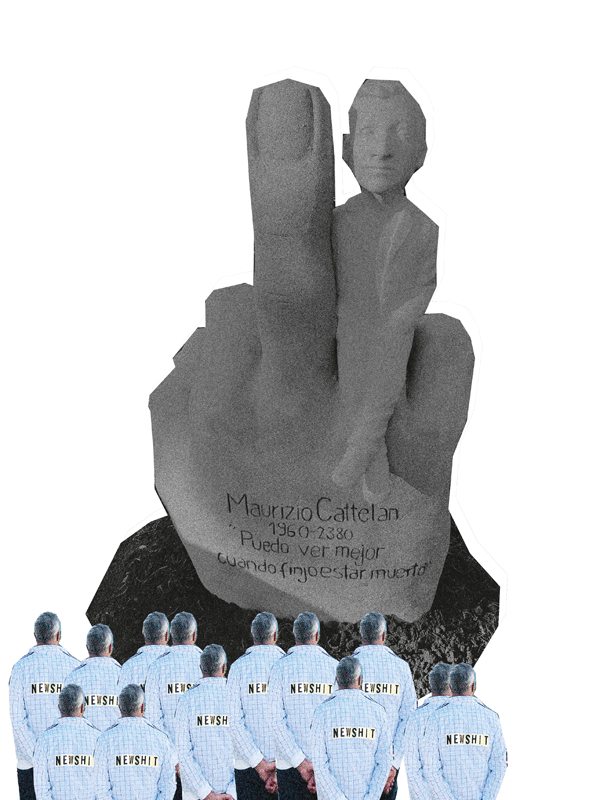

How ironic that at such a precarious moment in its history, what brought us to Buenos Aires was a project called Eternity that consists in a pop-up cemetery for the living. Given recent events, it could also just as easily be a cemetery in which to bury the nation’s debt. Programmed as part of Hopscotch (Rayuela), a multifaceted event curated by Cecilia Alemani for Art Basel Cities, Eternity brought together more than 200 local artists who each submitted their interpretation of a tombstone. Tenderly caustic and playful in their depth, they bore witness to the vibrant creativity of porteño artists.

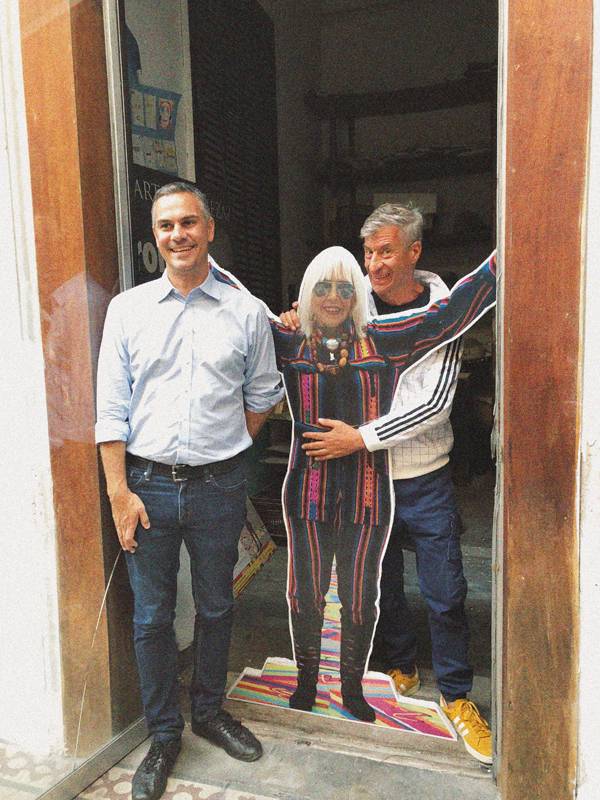

Massimiliano Gioni and Maurizio Cattelan.

The rest of Alemani’s programming for Hopscotch (Rayuela) was, like the curator herself, overflowing with wit and vivacity, bringing art into the most unlikely places in the city without taking itself too seriously. It was as refreshing as it was stimulating for its different audiences. The title Hopscotch (Rayuela) is borrowed from the experimental novel by the Argentine author Julio Cortázar, which is structured according to a nonlinear narrative and which, like the traditional playground game, functions in different sequences. From an abandoned silo to a former German brewery, Alemani’s lighthearted itinerary mixed Argentine and international artists. Among the highlights were Eduardo Basualdo’s revolving doors (Perspective of Absence), which opened onto the immensity of the Rio de la Plata at the end of an 800 m-long pier belonging to a fishermen’s club; Alexandra Pirici’s mesmerizing “performative environment,” which featured 60 or so performers drifting and dancing through the space for hours on end; Alex Da Corte’s Kermit the Frog, Even, an 18 m-high Kermit balloon that was displayed half deflated in a former power plant; and Barbara Krueger’s monumental Untitled (No puedes vivir sin nosotras/You Can’t Live Without Us), a large-scale mural fresco painted in the colours of the Argentine flag on the side of an abandoned grain silo opposite the Ponte de la Mujer (“bridge of the woman”). À propos, we couldn’t help but notice the recurrence of queer and feminist themes on the Argentine arts scene, especially at a moment when the progressist pocket of the population was – yet again – fighting for the legalization of abortion; while we were there, a “green wave” of women wearing emerald-green scarves (whence the name they’d chosen for their movement) was demonstrating across the country in support of the cause.

So here we were, between two Hopscotch (Rayuela) stops, visiting galleries in Villa Crespo. Among all the people we met, there wasn’t one who didn’t mention Fernanda Laguna, a local artist, poet and general cultural agitator. In 2000, when the worst economic crisis in Argentina’s history reached its peak, Laguna founded the now legendary artist-run gallery Belleza y Felicidad (“Beauty and Happiness”), which for many years was the crucible for all the emerging art and literature in Buenos Aires. She later moved the gallery to a favela (which in Argentina are known as villas miseria, or misery towns) on the outskirts of the city, where it evolved into an experimental artbased education project for disadvantaged children and teenagers.

Intrigued by Laguna’s career path, we went to see a piece she was showing in a group exhibition a few blocks away at Nora Fish gallery. We ended up talking about the history of Latin American feminist movements with Fish, who was also showing a great show by Adriana Bustos. The conversation turned towards the pressure artists in this part of the world find themselves under to express a certain form of “regionalism.” As Fish explained, “Artists here aren’t expected to work on beauty, material or form. They’re systematically, and often wrongly, linked to themes about indigenous peoples, gauchos, the desaparecidos [the “missing” of the military dictatorship] and Evita Perón – even if most of them don’t go anywhere near those subjects.” The conversation made us realize how much the temptation of exoticism could be an issue as soon as one leaves the main art centres – bascially New York, London and Paris – and to what extent, despite a supposed open-mindedness in the art world, classification according to regional clichés could be experienced by artists as a curse that’s difficult to break.

We ended our tour at Buenos Aires’s oldest gallery, Ruth Benzacar, where Benzacar’s daughter Orly explained to us all the difficulties she has in representing only Argentine artists – a deliberate choice on the gallery’s part – in an art world that is centred on Europe and the U.S. We were soon joined by Catalina Urtubey, the director of El Gran Vidrio, a cutting-edge gallery located in a former petrol station in Córdoba. “Very few artists have managed to break through onto the international market,” she explained, “and once they do, they leave the Argentine scene for good.” It nonetheless seemed to us that things were changing. We met several artists from the new generation who were not only anchored in Buenos Aires but also had clear international perspectives and reach. Our lodestar in the city was Luna Paiva, a beguiling polyglot whose practice started with photography before evolving towards largescale bronze sculpture. Besides taking us to the best parrilla in town – Los Platitos’ bife de lomo makes you forget it’s the fifth time in a row you’re eating meat – Paiva introduced us to one of the oldest foundries in the greater Buenos Aires area, run by three brothers in the neighbourhood of Vicente Lopez. She works there with the founders who have made most of the sculptures you find in the city’s public parks, along with most of the monuments in Argentina. Paiva was finishing a series of bronze versions of a basic plastic chair for an upcoming project at Faena Art Space in Miami.

We also met Nahuel Vecino in his brightly lit La Paternal studio. Vecino’s work, was familiar from a show organized a few years ago in the Los Angeles space Del Vaz Project by young polymath called Jay Ezra Nayssan, which gave us a sense that smaller structures could be more beneficial and give a nuanced sense to transnational art movements. Vecino’s work mixes references from Buenos Aires shantytowns and dark places with a serene Renaissance style and Greco-Roman divinities. A memo on his wall reads “Chardin, Boucher, Balthus,” and a book on his coffee table is titled Treasures from Tunisia’s Bardo National Museum. We also paid a visit to artist Elena Dahn, who was clearly warding off any sense of “regional art” by working essentially on forms and material through the careful and performative manipulation of her latex-based sculptures-cum-paintings. Finally, and in a totally different style, we ended up at legend and PopArt mentor Marta Minujin’s extravagant house, where the 75-year-old artist has gathered together pictures of herself with Andy Warhol, maquettes for her acclaimed Documenta 14 project in Kassel (a reenactment of her 1983 project The Parthenon of Books), and an army of assistants working on her experimental paintings.

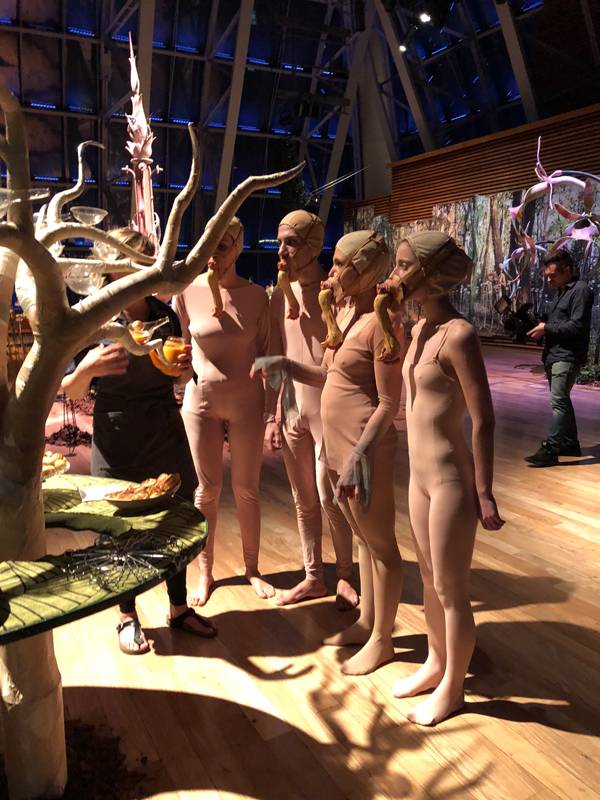

It was obvious to us that the city of Buenos Aires was aware of the importance of artists for its own development. Art Basel Cities was itself part of a larger project of urban development focusing on the southern fringes and the dodgy touristy neighbourhood of La Boca. There, Fundacion Proa has developed a second space dedicated to emerging artists, Laboratorio Proa 21 where we met Dani Zelko, who was installing a piece about police violence in the neighbourhood. Public institutions were all dolled up and ready for an international crowd to slide in: MAMBA and MALBA both opened shows featuring major pieces of Latin-American art – notably Abaporu (1928) by Tarsila do Amaral, considered the South American Mona Lisa, at MALBA; while CCK (located in the former national post office, one of the most impressive buildings we saw) had organized a dreamlike food performance by artist Nicola Constantino. Private initiatives were also blooming, among them BSM Art Building, founded by real-estate entrepreneur and collector Guillermo Rozemblum, which offers working space and support to a rotating group of artists including Max Gómez Canle, Leandro Asoli, Andrés Aizicovich, and Eduardo Basualdo. Special mention to the Museo Xul Solar, a gem that features the artist’s singular vision of a utopia focused on the creation of a universal language. We ended the week at a performance and dinner put on by hotel magnate Alan Faena, of Faena Art Center fame (Buenos Aires and Miami), and one of the best parrilleros we encountered. Given his ability to grill meat perfectly, we enquired about his other gaucho qualities. “Do you ride horses?” we asked. “Here we ride the impossible,” he answered. “We have no choice!”