“Asking why Art Basel is the most important fair is like asking why Venice is the most important biennale. It’s because the whole art world is there. I come here to make contacts that would be impossible to make in such a short time elsewhere,” says Dirk Snauwaert, artistic director of the Wiels contemporary-art centre in Brussels. Over the years, Art Basel has become a jealously guarded brand, as evidenced by the lawsuit it brought against Adidas, who used its name without permission on a pair of sneakers. What distinguishes Art Basel from its competitors? Its quality and longevity for one. It was as part of this “brand,” or community, that some of its exhibitors – like Kamel Mennour and Jocelyn Wolff – made a name for themselves. Although it took time to incorporate young galleries and those from emerging countries, the fair has taken the evolution of artistic practices into account by, for example, providing spaces for large works with Art Unlimited, a concept borrowed from biennales and used by other salons. But above all, it’s figured out how to replicate itself abroad.

“Asking why Art Basel is the most important fair is like asking why Venice is the most important biennale. It’s because the whole art world is there.”

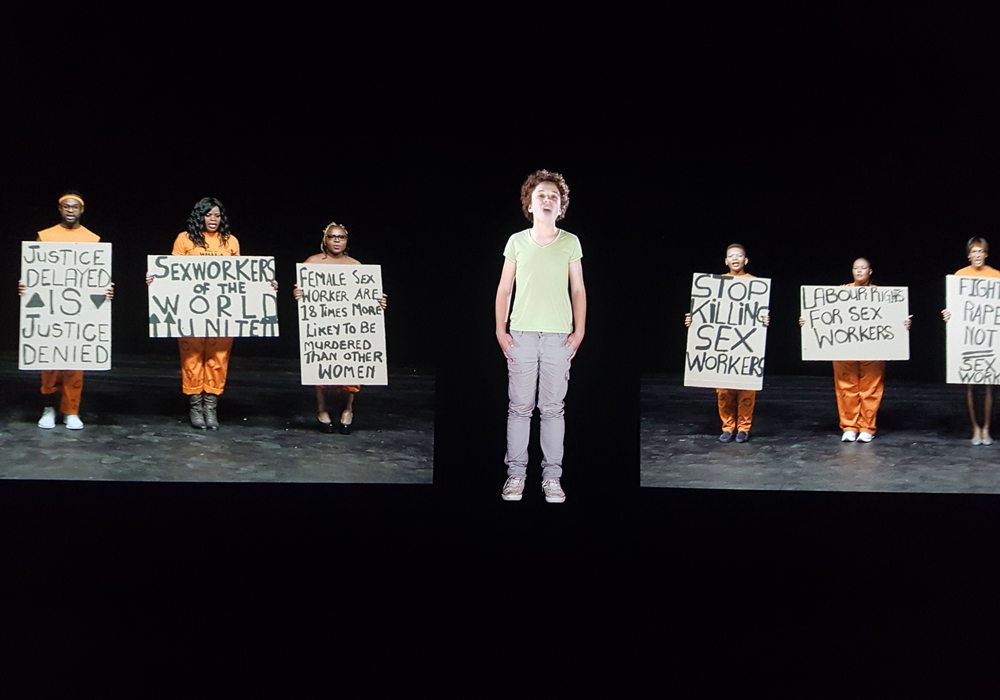

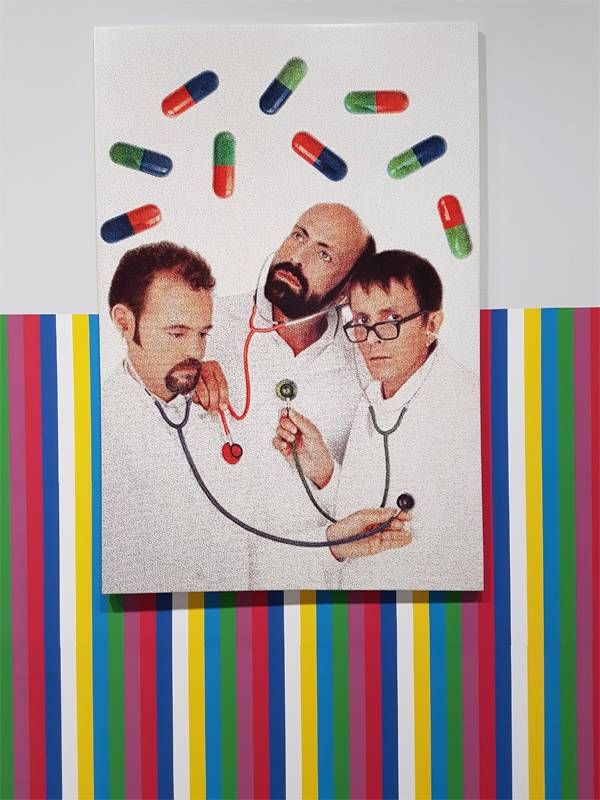

Detail from General Idea's installation exhibited at Art Basel Unlimited 2018.

Nothing suggested that the Calvinist city of Basel would one day become an art mecca. In 1967, Cologne took the lead by creating a fair, Art Cologne, which quickly became a must. In 1970, three Swiss gallerists – Ernst Beyeler, Trudi Bruckner and Balz Hilt – set out to compete with it, rallying 90 exhibitors the first year. “They hit their target,” recalls former Basel dealer Gerard Schreiner. “When I visited the fair in 1970, I was extremely impressed by an unknown who was cutting his left shoulder slightly with a razor. A trickle of blood slowly ran down to the crack of his buttocks. The visitors watching said that, at one point, the trickle of blood caused a very visible orgasm. The following year, the organizers chose another path!” From the beginning, the competition between exhibitors raged, for better or for worse.

From the beginning, the competition between exhibitors raged, for better or for worse.

In 1973, Marcel Fleiss, who had bought part of Marie Cuttoli’s collection, including a very large Calder stabile, sold everything on his stand. “Unfortunately, word got out very quickly and resulted in my elimination the following year, probably due to the jealousy of the other sellers on the admissions committee,” he recalls. “I waited until the 1990s, during the crisis, to find my place, with fewer applicants and a new selection committee.” In 1975, the fair had some 300 exhibitors, including a good number of Americans eager to diversify their client list. But in the late 1980s, Art Basel experienced a slump. “At the time, the two major international fairs were Art Chicago and Art Cologne,” says Marc Spiegler, current director of the fair. “Art Basel was going through a real crisis.” Three important sellers – Pierre Huber, Gianfranco Verna and Felix Buchmann – developed an original concept, breathing new life into the event. “Lorenzo Rudolf, who ran the fair from 1991 to 2000, was wise enough to listen to their ideas,” Spiegler continues. And what were they? A new visual identity, a new logo, and a reduction in the number of exhibitors.

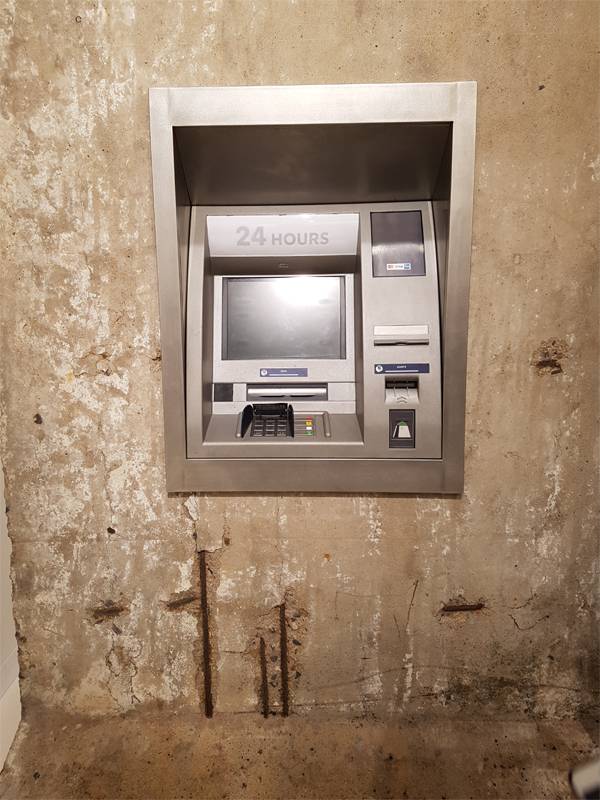

Installation from duo Elmgreen Dragset presented by the Koenig gallery at Art Basel 2018.

The facelift was even more spectacular when Samuel Keller arrived at the helm in 2000. Bright, pragmatic and charismatic, this communications wizard quickly became a media darling. The Keller era was marked by parties that made the Swiss city feel great. But it was also the launch of new offshoots and gatherings that drummed up the hottest curators. Most importantly, Keller succeeded in exporting the fair to Miami, in 2002. The choice was a surprising one. For some, this Florida city that reeks of crime and debauchery à la Miami Vice or Scarface is a true melting pot; for others, it’s a tropical death row for wealthy pensioners. But the gamble paid off, and attracted the cream of Latino collectors.

Even though glitter reigns there supreme, Art Basel Miami Beach remains haloed in the mother fair’s aura of professionalism.

Even though glitter reigns there supreme, Art Basel Miami Beach remains haloed in the mother fair’s aura of professionalism. Moreover, it catalyzes the city’s energies. Local bigwigs have redoubled their efforts by expanding their private spaces. New institutions, such as the Pérez Art Museum, have emerged. “The fair has given greater visibility to museums, which have become places where artists want to show their work. When you ask an artist to exhibit there in December, something happens, you see a smile appear on their face,” says Silvia Karman Cubiñá, director of the Bass Museum. After conquering America, Art Basel then set sail for Asia: in 2011, its organizers “bought” the Hong Kong art fair and, two years later, re-baptized it Art Basel Hong Kong. It’s now a must in Asia. “Art Basel has helped strengthen Hong Kong’s position as an artistic hub and put it on the international stage,” says Kevin Ching, managing director of Sotheby’s Asia.

These foreign versions marked the beginning of a branding exercise. “At some point, people started saying, ‘We’re going to Basel,’ not referring to the city but to the fair,” says Spiegler. Art Basel followed the classic models of brand stretching: create a new product in an old market, or introduce an old product in a new market. And in each instance, the fair found a foothold in a “nexus town,” a geographical crossroads where the cultural offer, though not inexistent, wasn’t so great. To make these new versions a success, Art Basel has several trump cards: the coherency enshrined in a graphic charter common to the three events, identically-structured selection committees, and, most importantly, a relationship of trust with the exhibitors, who know the fair will live up to its promises.

“At some point, people started saying, ‘We’re going to Basel,’ not referring to the city but to the fair,” Marc Spiegler.

“Art Basel could create a fair in some remote corner of the world, and it would undoubtedly be successful,” said Jose Freire, of Team Gallery. “A fair’s novelty wears off after two or three years. A restaurant is full the first two months because it’s new, but afterwards because the food’s good,” says Spiegler. In Hong Kong, Art Basel is all the more impressive because, as Radha Chadha and Paul Husband’s book The Cult of the Luxury Brand: Asia’s Love Affair with Luxury stresses, Asia loves brands.

Art Basel’s thing, however, is avoiding monotony, unlike the big brands that offer the same products in every country. “Even if the meals are served on the same plates, they taste different,” says Spiegler. “The uniformity is in the quality of the programming.” And the programme is interesting enough that artists, hitherto resistant to fairs, visit in large numbers. “Of course, the fair can be a hysterical place, like the opening of a buffet at a cocktail party where people all jump on the €50,000 hors d’oeuvres, but it’s also a place where the economic world is visible in a realistic way,” says one of them. But the further up the ranks it moves, the more selective the fair must become, which means turning away deserving figures at each edition. Even old stalwarts have been asked to pack up their bags. “In the world of dynamic art, if no one leaves, no one can enter.” explains Spiegler.

Art Basel and Art Basel Unlipmited, June 14-17, Basel.

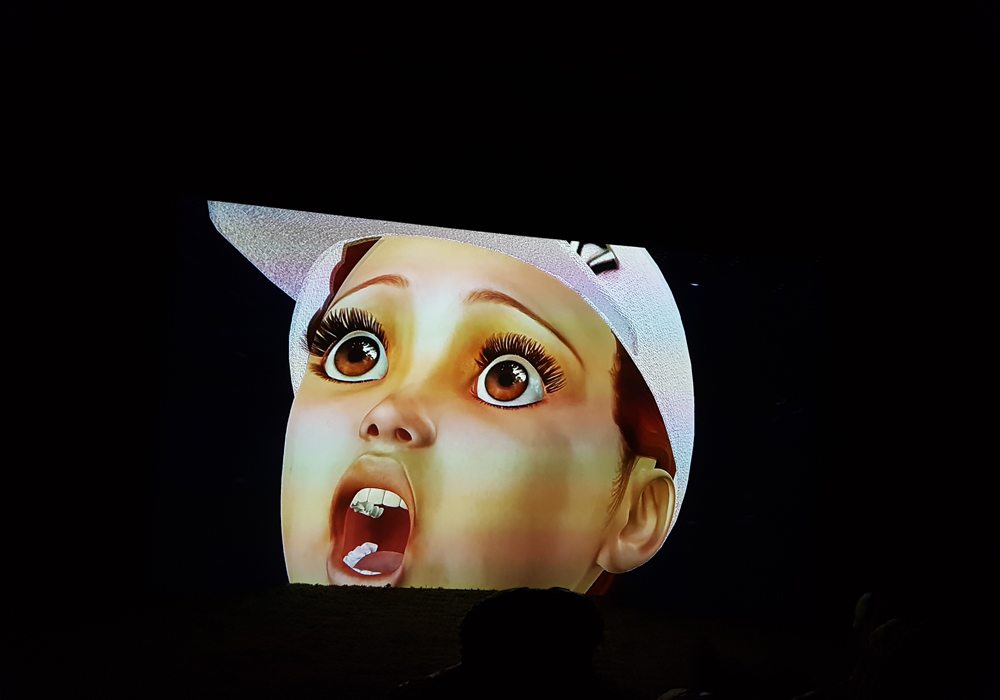

Clip from Richard Mosse's video presented at Art Basel Unlimited 2018.