So what could Danish artist Olafur Eliasson, invited to create this year’s artworks in the gardens at Versailles, have come up with to make people forget the misadventures of his predecessor? In 2015, one of the installations by Anglo-Indian artist Anish Kapoor caused a scandal – or, to be more precise, had its little 15 minutes of fame on national news – and was afterwards defaced by prudish extremists. “Degrading” is how these uptight anti-Semitic vandals (with very mediocre graffiti skills) described a giant work that obvisouly made reference to female genitalia, and which was instantly nicknamed “the queen’s vagina.” In the face of such crass stupidity, did Eliasson believe an enema was necessary? Whether or not he was thinking of the purifying virtues of water, it is indeed this substance, in its liquid, solid and gaseous forms, that will be at the heart of his monumental interventions in the gardens of the Château de Versailles, from 7 June to 30 October.

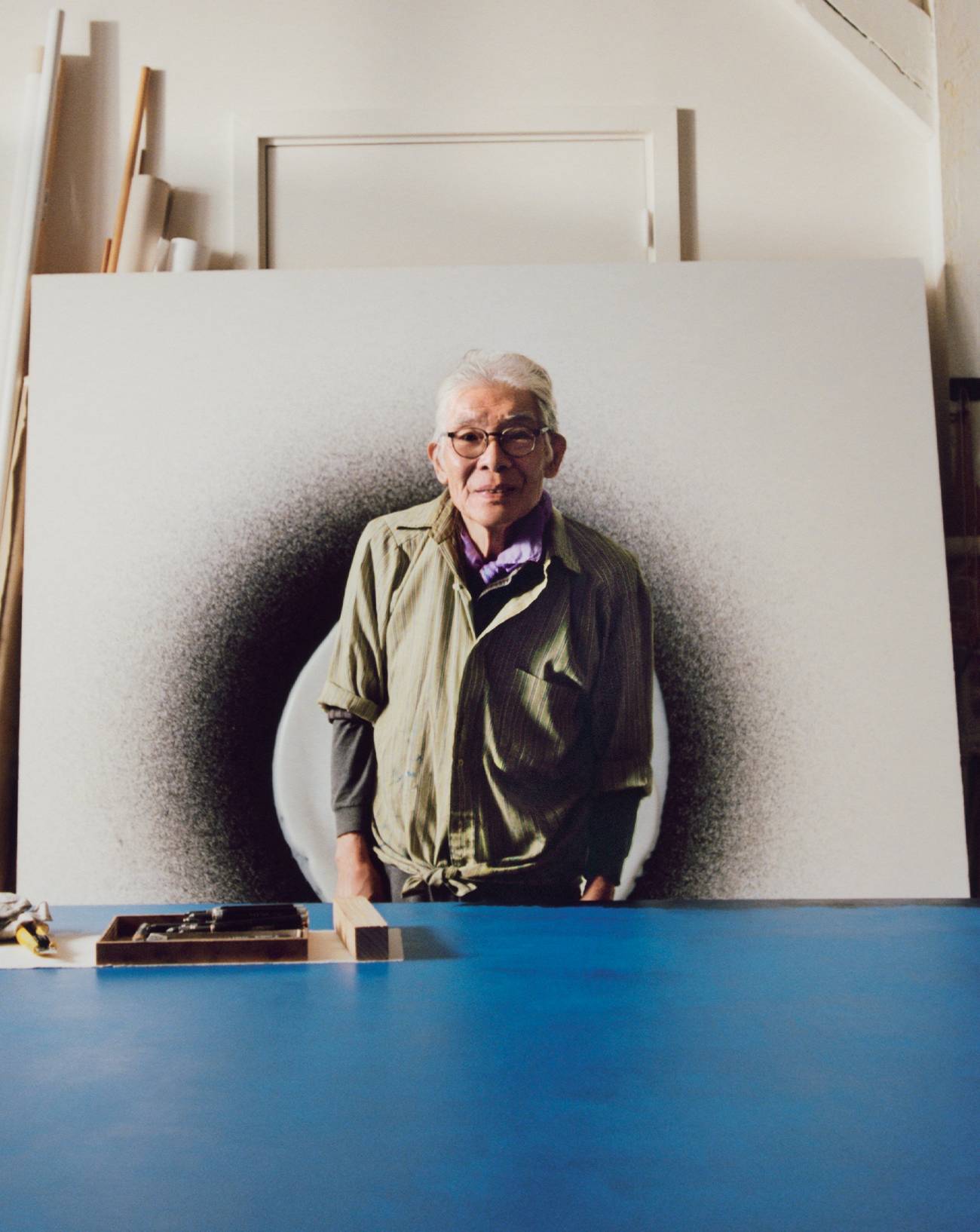

In France, the 49-year-old artist is preaching to the converted. One of his first major exhibitions, among those that propelled him to the forefront of the contemporary-art world, was held at the Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, while in 2014 the Fondation Louis Vuitton hosted his Contact show. In between these two events, Eliasson had been honoured by all the big international art institutions. His Weather Project at Tate Modern in 2003 saw him install a giant sun in the Turbine Hall which produced a mysterious halo through an artificial mist. “I work with natural phenomena, with light and the ephemeral,” explained Eliasson when Numéro met up with him in a salon at Paris’s Plaza Athénée a few weeks before the opening in Versailles. “My idea in Versailles is to create a tangible experience of water in all its forms. Obviously the idea of dematerialization interests me, as well as psychology: I always think about how the public will experience and mentally grasp the exhibition.”

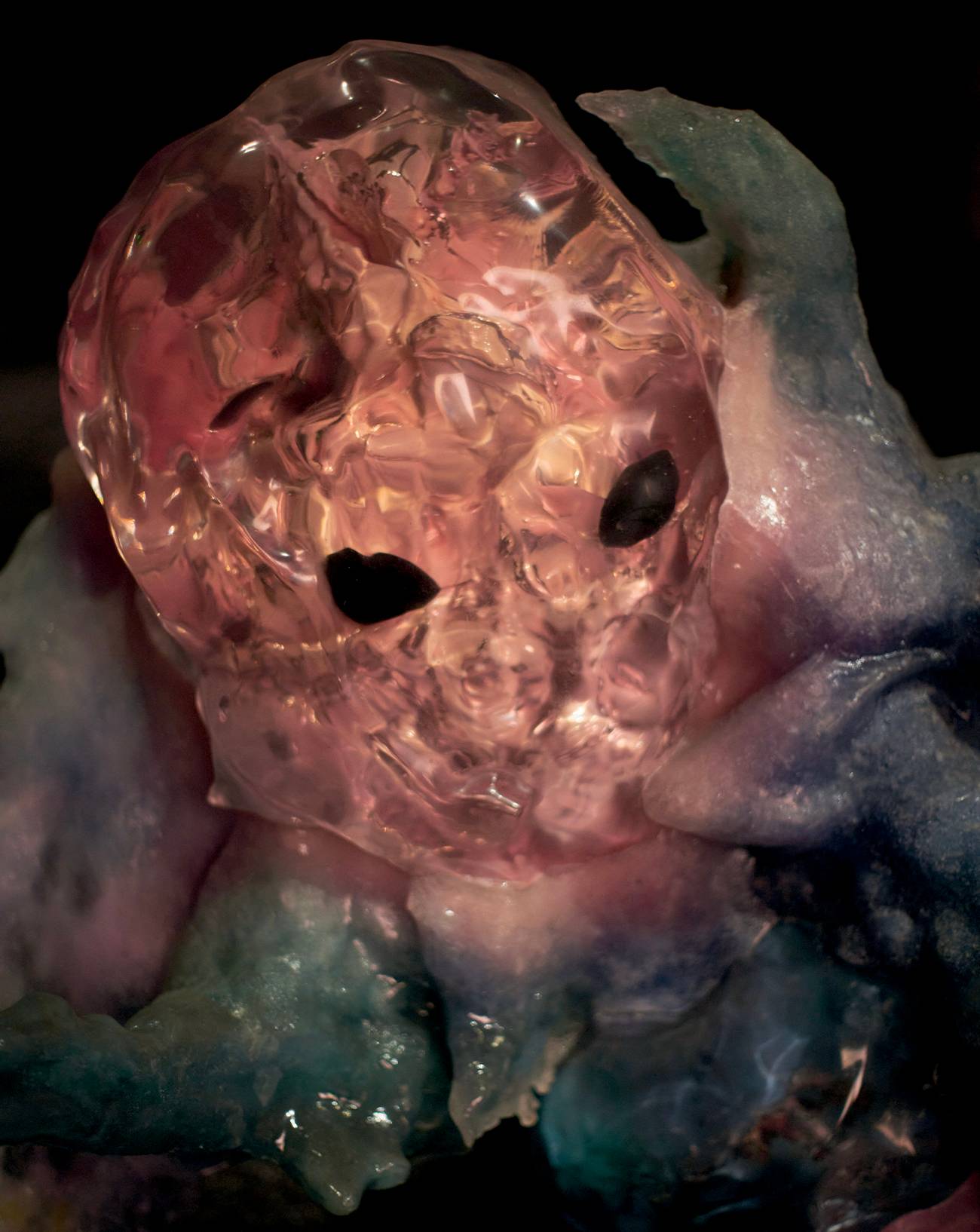

Eliasson’s three interventions in the gardens at Versailles should procure visitors a sensational spectacle. No less than 40 staff (out of the 100 at his Berlin studio) worked on the project. The first, and probably most impressive, intervention will consist in an immense cascade in the axis of the Grand Canal. “The idea of a cascade had been abandoned at the time of the gardens’ creation for technical reasons,” he explains. “For me, this project is a way of making what was impossible yesterday possible, of making the dream become reality. Throughout my art training I was fascinated by the theatrical power of the Baroque, which is fully expressed at Versailles. But the use of this style interests me more for its capacity to underline the presence of an idea, to say everything through a detail, to deepen a sensory and critical ability, than as a melancholic escape into the past.” Meanwhile, in the Bosquet de la Colonnade, Eliasson will reprise his intervention at Paris’s COP 21, bringing in blocks of ice directly from Greenland which are rich in minerals that will fertilize the earth. The end of a world is thus transformed into the possibility of a new start. “Greenland’s layers of ice are made of snow that accumulated over hundreds of thousands of years,” Eliasson explained in 2015. “The ice contains the memory of all the changes undergone by the climate and the atmosphere.”

This singular relationship between the artist and time could not have found a better receptacle than Versailles. “Versailles travelled through the centuries to meet me. But I also undertook my part of the journey,” he explains. “Of course I had in mind what I’d learned at school about Louis XIV and about the French Revolution. But also a much more recent event: the Congrès du Parlement called by François Hollande following the terrorist attacks in November. Versailles is a place of history, past history of course, but also totally contemporary history. I want to make of Versailles a place of contemporaneousness.”

Since his beginnings, Eliasson has always considered cultural institutions as forums that citizens should reappropriate. “I begin a story through my works, but it’s the visitors who finish it through their presence. The work only exists because a spectator experiences it.” But will we see a citizens’ reappropriation of the gardens in the manner of the Nuit Debout movement in Paris? To his detractors, who say his recent work is more like a heartfelt publicity campaign than an artistic gesture (which is supposed to be more radical or courageous), he seems to reply indirectly when he talks about the frenzy he would like his works to provoke. He hopes, for example, that the imposing circular structure that will create a cloud of fine vapour in the Bosquet de l’Étoile “will not only bring forth rainbows and other light-related phenomena but will also encourage the public to run through and around it in a gesture of madness.”

Experiences, sensations, a sense of self consciousness when confronted with natural phenomena − Eliasson’s major themes will all be present, including the theme of exploration, which seems particularly to grip him at Versailles. “I was lucky enough to be able to walk around alone, at night, in the château,” he confides. “I just had a little solar-powered pocket torch that I developed with my studio. I opened hidden doors and went down stairs and along corridors reserved for the servants. The vibrations I felt fed into my artistic intervention.” This exploration inspired a second series of subtle, ephemeral works that will blend in perfectly with the architecture of Versailles. Remaining hazy about the details, Eliasson prefers to outline the main ideas behind his intervention. “It won’t be a question of traditional objects installed on pedestals. Some of them can fit into the palm of your hand. Visitors who aren’t ready to explore Versailles as I did might miss them.” Among the objects he refers to could well be an eye, that of the château itself. “Through my intervention I wanted to bring about a reversal. It’s no longer the spectator looking at Versailles, but Versailles looking at the spectator.” A play of mirrors − a symbol of Versailles if ever there was one − will no doubt be involved. “I wondered what a mirror really sees, what its subconscious might be,” he concludes mysteriously.

This water magician and shaman of modern times is never short of slogans that hit the nail on the head. Especially when it comes to promoting his latest product, the Little Sun lamp with its humanitarian aims (originally intended to come to the aid of poor African countries), the same model that allowed him to discover Versailles by night. “You can buy it in the shop at the château,” he enthuses. “For Ä22, everyone can become a Little Sun King!”

Olafur Eliasson at the palace of Versailles in 2016, 7 June to 30 October.