Three Soviet soldiers tower over the ruined city of Berlin, proudly displaying the red flag at the top of the Reichstag building. Captured on May 2nd, 1945, the photograph immediately went down in history. Since then, it has symbolized both the defeat of the Nazis and the power of propaganda in school textbooks. At the Papillon Gallery in Paris, that familiar image reemerges in an intriguing manner - a disquieting strangeness, surely due to the presence of the main character, who seems to be drawn, while the foreground is hyper-realistic. Actually, where are his two sidekicks?

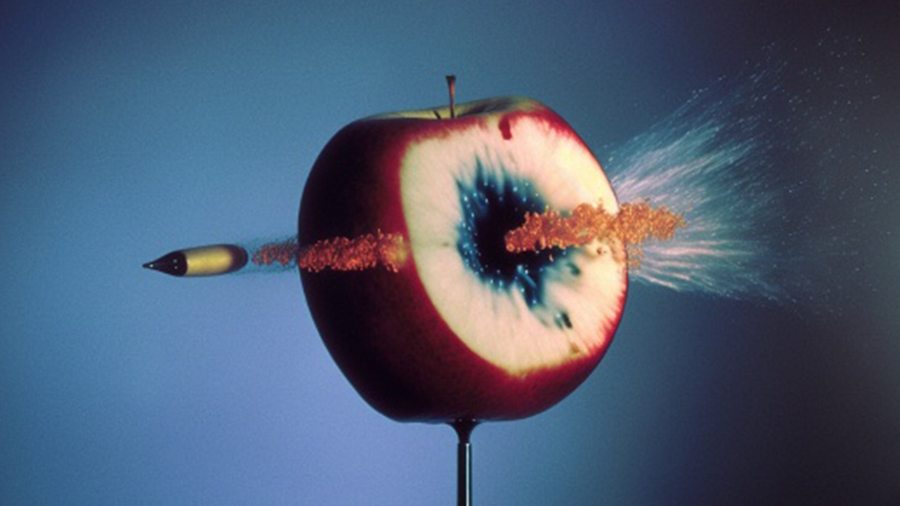

This image is in fact a creation of the artificial intelligence Midjourney, which allows anyone to produce images from text descriptions. The artistic duo Brodbeck and de Barbuat fed content to the machine for several weeks to recreate multiple iconic snapshots of the 20th century. As the name of the original photographer was never mentioned to the AI, the French artists only provided the best textual description they could of what was represented in the first version. For the visitor, the exercise turns into both a game of the 7 errors and a game of reflection - what do we really remember when we are overflowing with images from our collective visual memory? One detail should have immediately stood out here. The red flag is not adorned with the usual Soviet emblems. The hammer and sickle are reinterpreted by the machine as symbols more akin to Japanese Kanji. “Artificial intelligence is more than capable of recreating a flag, a sickle and a hammer,” Simon Brodbeck declares jokingly. “Yet it has been limited by man. Its creators have especially forbidden it from representing any form of ideology or propaganda. That way, the AI considers the Soviet flag as such and therefore refuses to represent it... Whereas reproducing the American flag is not a problem.” Needless to mention that Midjourney is an American company...

Ironically, the photograph taken in May 1945 had also been edited before its publication. One of the three Soviet servicemen proudly sported a watch on each wrist, and to avoid any accusation of looting, they had been erased from the final picture... The art of editing images used to be Stalin’s speciality. He would edit his face to give it a smooth appearance and conceal his skin condition, which had been damaged by smallpox when he was a child, or, more seriously, he would remove former comrades, who fell victim to his purges, from official group pictures. Historical falsification didn’t wait for artificial intelligence. As photography aficionados, the duo Simon Brodbeck and Lucie de Barbuat are well aware that an image is everything but neutral. Their aim today is to dissect that lack of neutrality at the heart of AI. “This power of falsification is not the responsibility of the machine,” Simon Brodbeck emphasizes, before adding: “It is a mere tool. Its biases come from the limits imposed by its human designers and the source images it has access to in order to generate its own visual content.”

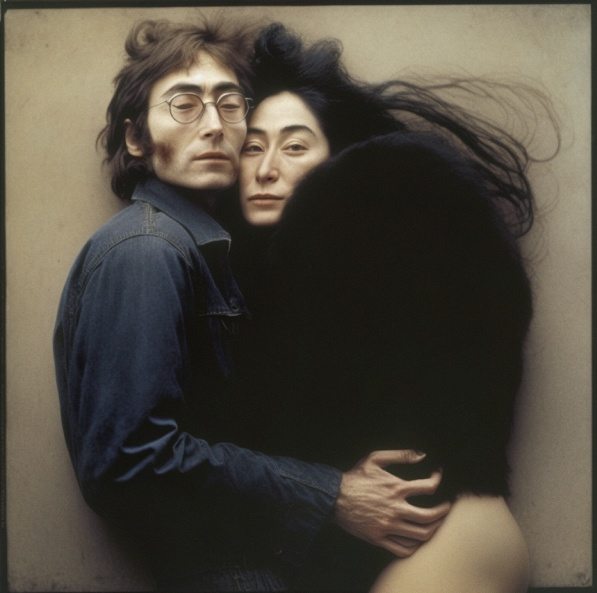

Racist and sexist biases are among the best identified. For instance, Annie Leibovitz’s iconic portrait of John Lennon (naked) and Yoko Ono (clothed) is reinterpreted in a stereotypical way by artificial intelligence. John Lennon is now all dressed up, while Yoko Ono appears half-naked, with her buttocks visible. “It probably happened because the AI considered that, like in most existing images of this type available to it, women are more often naked than men,” Simon Brodbeck comments. Thus, a whole collective unconscious emerges within the exhibition, unveiled in a series of “synthetic” and problematic pictures.

The award for digital drift goes to an AI’s reinterpretation of a famous image shot by American photographer Margaret Bourke-White. Following the major flooding in Kentucky in 1937, the journalist captured several African-Americans queuing up in front of a relief station through her lens. In the background, a huge billboard advertised a rich, white family in a car with the double slogan: “World’s highest standard of living” and “There’s no way like the American way”. Reproduced by artificial intelligence, the white family of the advert appears clean-cut. Each member is distinct, each face is sharply defined. Yet the figures of the African Americans in the photo are much blurrier - their features are vague, even distorted, taking the shape of the worst racist caricatures from the 1930s. “This is a well-known limitation of artificial intelligence,” Simon Brodbeck shares. “We attribute it to the fact that there are fewer representations of black people in the data available to them at the moment. It is harder for them to draw their inspiration from it and create realistic faces.” Just as the algorithms of social media reinforce the prejudices of their users by suggesting content similar to the one already consumed in a downward spiral, the mechanisms of artificial intelligence as highlighted by Simon Brodbeck and Lucie de Barbuat worry as much as they fascinate. Yet, its technical virtuosity struggles to make us forget about an essential question: who’s in charge?

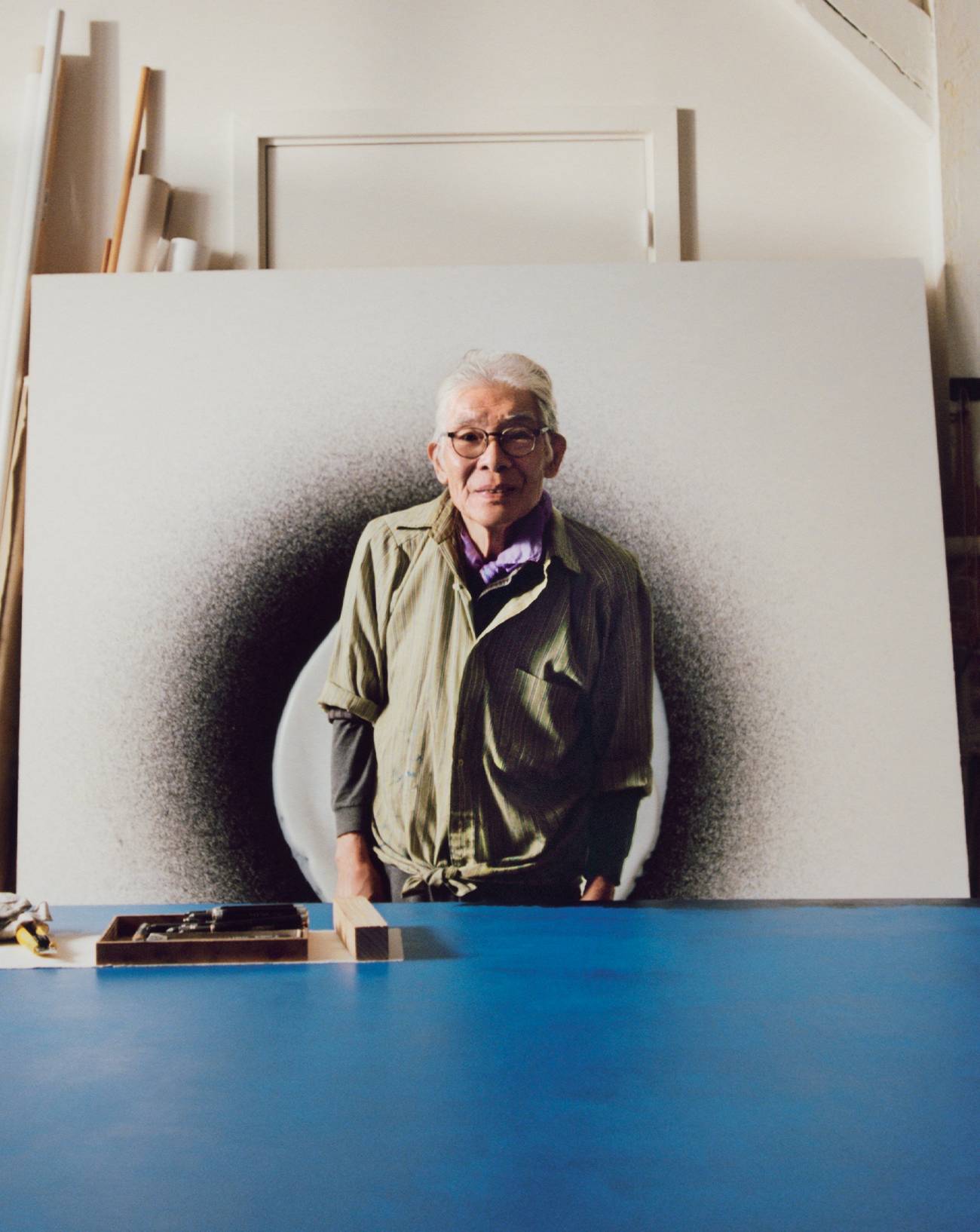

“Une Histoire Parallèle” (A Parallel History) by Simon Brodbeck and Lucie de Barbuat, open until January 13th, 2024, at Galerie Papillon, Paris 3rd arrondissement.