All of Marlene Dumas’s paintings and drawings reveal the body, full-frontal. The body takes control, loudly asserting its condition: carnal, disturbing, vulnerable, furious, subversive, mortal and impulsive, portrayed in undisciplined, challenging images. At the entrance to open-end, the exceptional exhibition curated at the Palazzo Grassi by Dumas and Caroline Bourgeois, two naked bodies, battling against any form of objectification or voyeurism, stand as subjects, one of them in provocative insurrection, the other in passivity. A naked young man looks down at his violet, erect penis. He is his own focus of attention, indifferent to what or who surrounds him. A woman, also naked, on her backside, raises her legs, shamelessly exhibiting her genitals, proudly staring us in the face. The two bodies dominate not only the space of the canvas but also the space of the viewer, who is immediately vanquished by their aplomb.

“Somewhere between description and suggestion, explicitness and subtlety, roughness and refinement. These bodies are ambivalent : their ghostly yet carnal presence haunts you for days.”

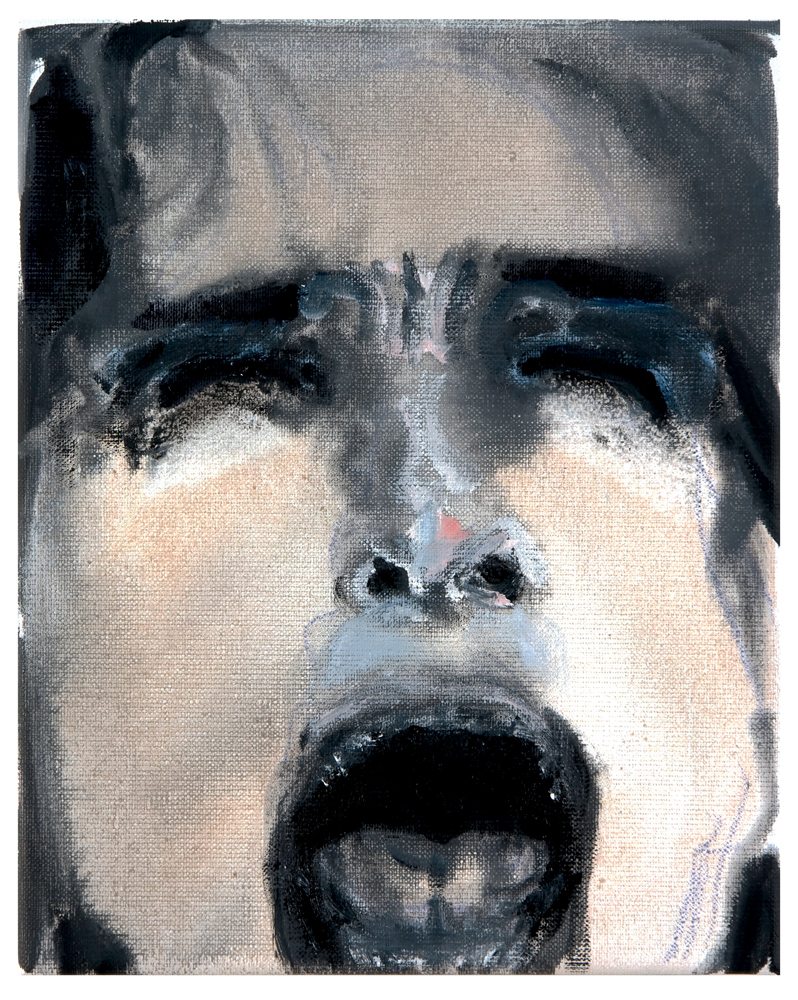

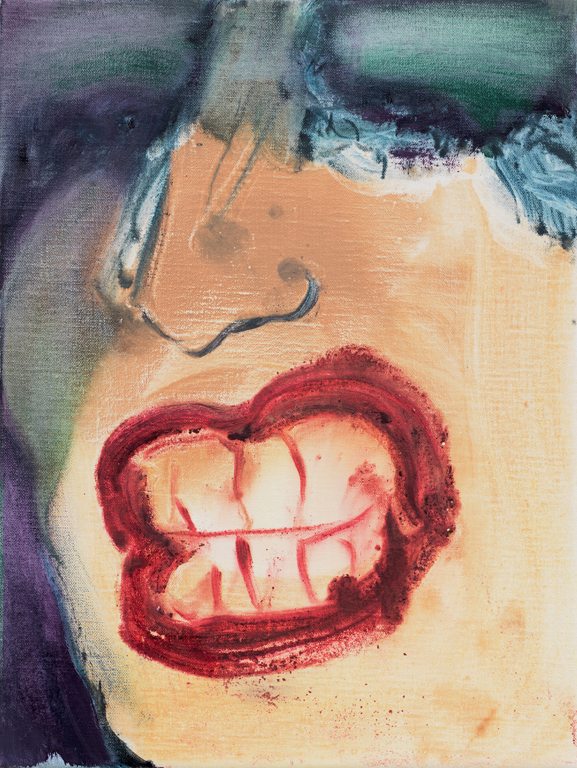

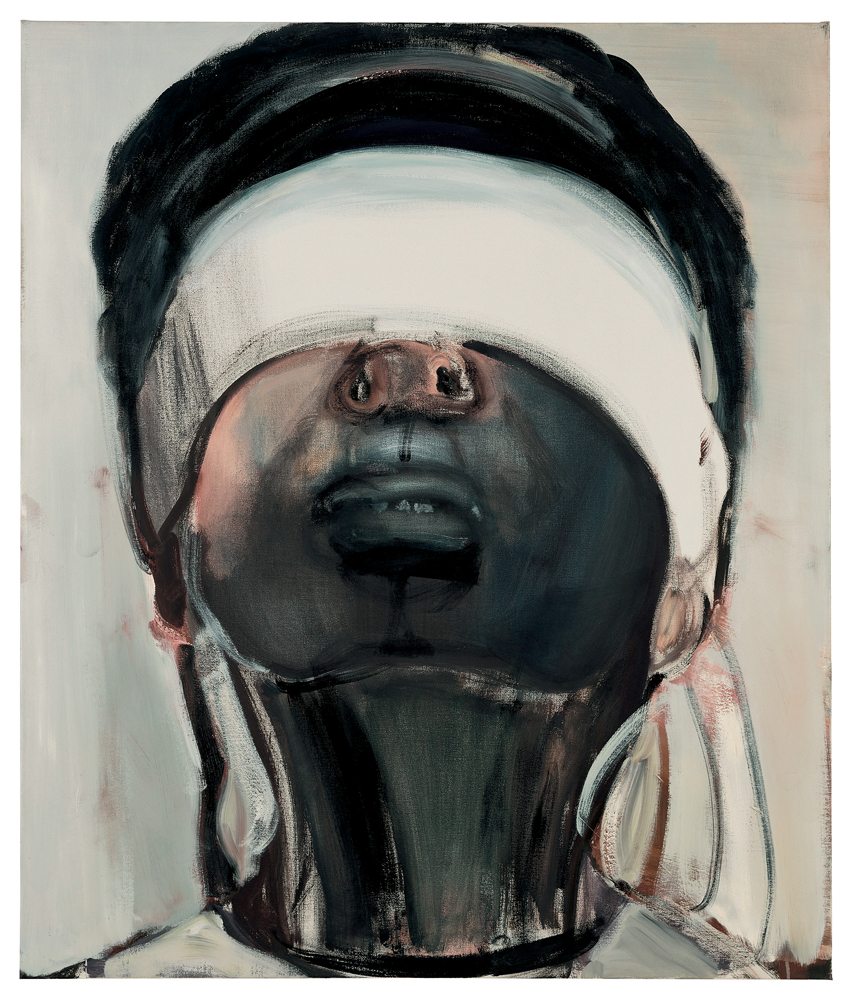

In Dumas’s work, the body is constantly struggling with its physical limits. First that of the frame, which locks it in so tightly that it has no choice but to explode from the canvas to strike down the visitor. Looking at a Dumas painting is like watching a film with 3D glasses. In fact it’s better, because it touches you. A hand reaching towards the bottom of the canvas, trapped by the edge of the frame, escapes into space to grab you the hand of a drowned migrant (Canary Death, 2006). The mouth of Lips (2018) kisses you, while that of Teeth (2018) bites you. Everything induces an interaction, a physical conversation that is embodied in the painting. You feel the brushstrokes in your skin the whole range of human emotions is summoned.

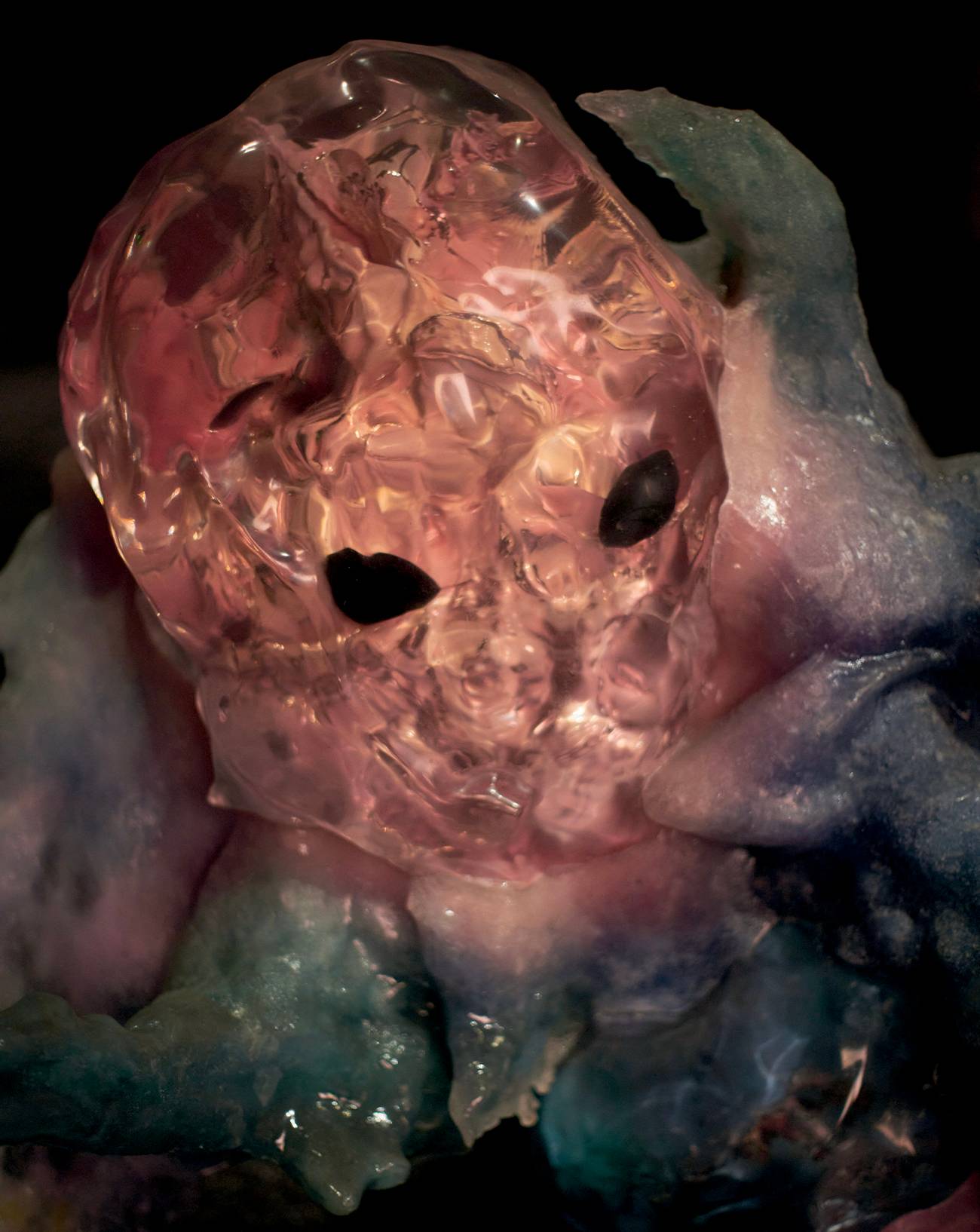

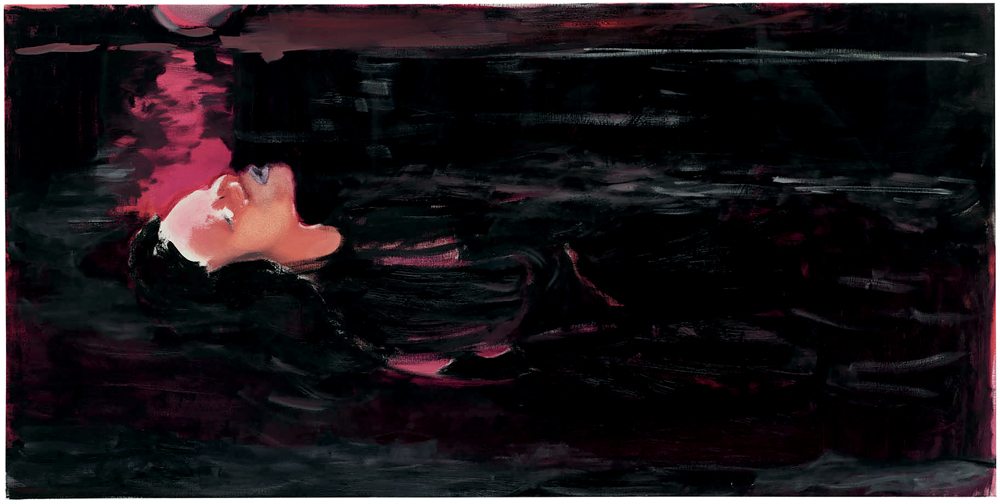

Bodies also struggle against their physical limits within the pictorial space. Brushstrokes can be quick as a flash, as though painted in a hurry, almost formless, and yet extremely precise, somewhere between description and suggestion, explicitness and subtlety, roughness and refinement. These bodies are ambivalent: their ghostly yet carnal presence haunts you for days. Their appearance is as potent as their disappearance, or rather their liquidity (Kissed, 2018). Bodies change, turning into a devastated landscape (Dead Marilyn, 2008) or a starry constellation, a body-cosmos (Io, 2008). Everything is irresolute, paradoxical.

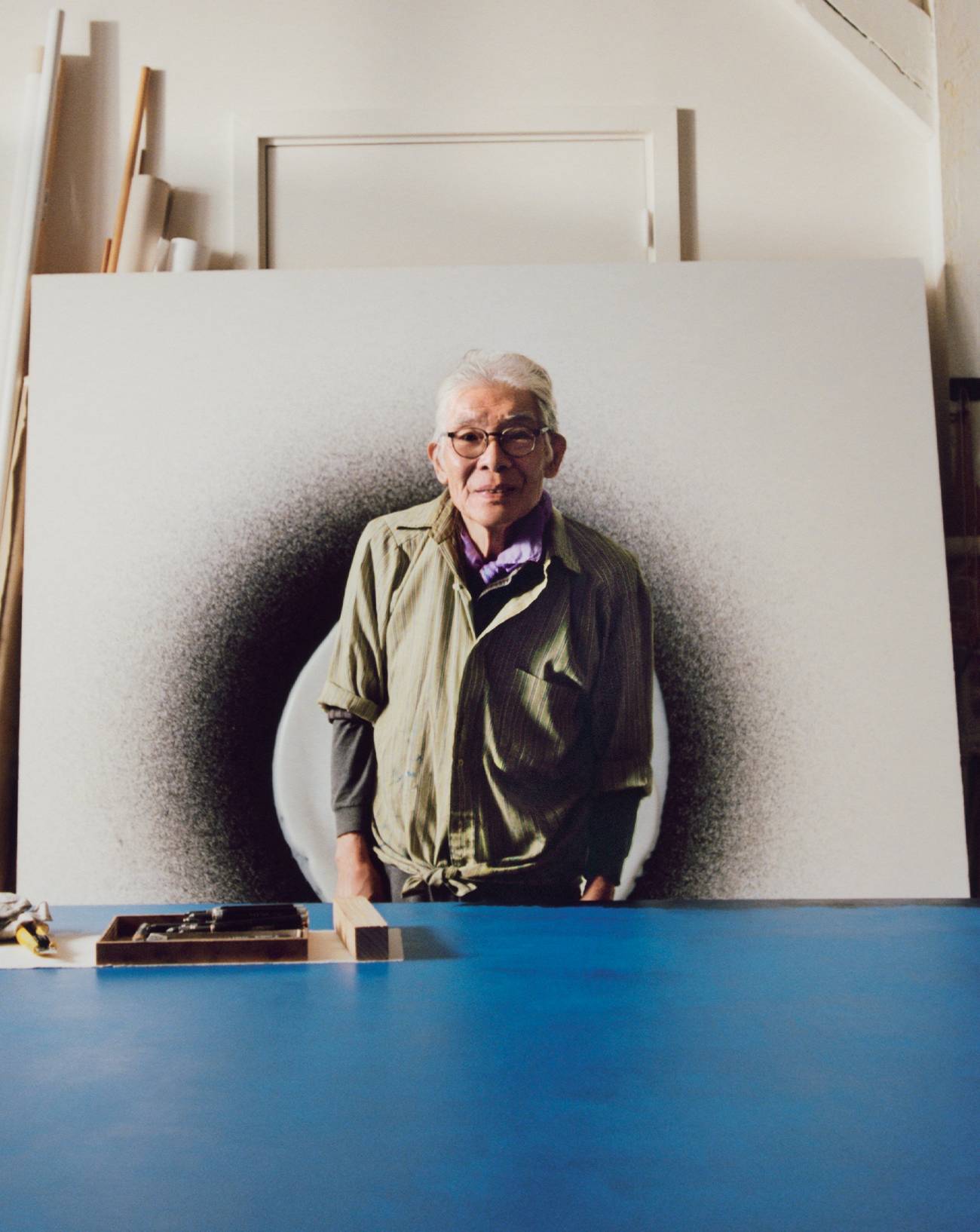

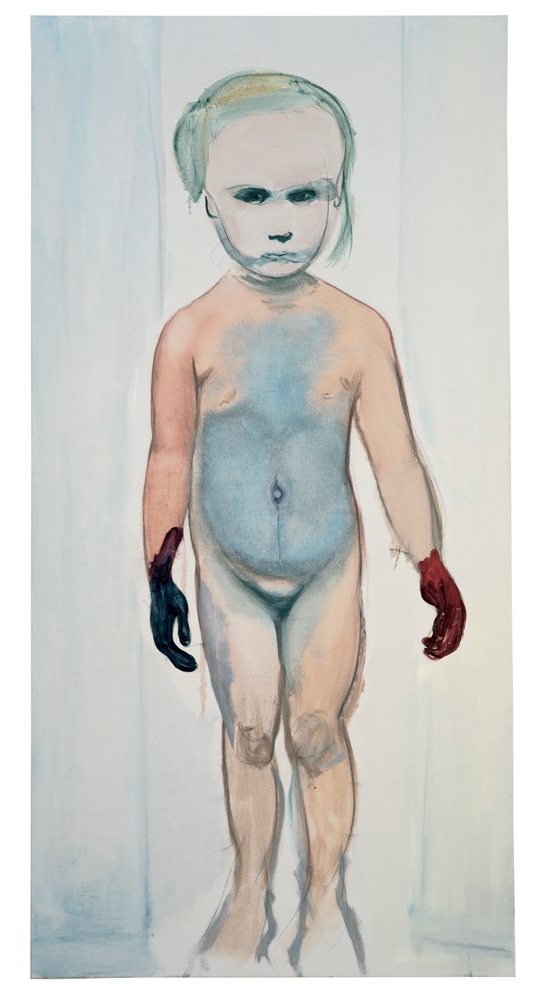

Dumas was born in South Africa in 1953. After studying art in the Netherlands, she settled permanently in Amsterdam. She is still deeply affected by apartheid and strongly rejects all forms of classification, whether by race or gender, as well as any form of assignment. She is only interested in individuals and the “wretched of the Earth.” Her women, of whom there are many, as evidenced by her reinterpretations of Venus, take responsibility for their actions. This empowerment is conveyed in her paintings not only by their attitudes, but also through reversals of composition. In The Visitor (1995), Dumas portrays five prostitutes. Contrary to convention, which would place the viewer in the client’s position, Dumas situates the audience behind the women waiting for their johns. Challenging the male gaze, she makes the viewer either a prostitute or a pimp, confronting us with the commodification of the female body.

“My best works are erotic displays of mental confusion .”

The work is never about the nude – men depicting women as objects of desire – but about nudity, sexuality or pornography. Buttocks fill the canvas (The Gate, 2001), fingers explore a gaping pussy (Fingers, 1999), the penis is positioned at the level of the viewer’s face (Alien, 2017), nipples are erect (Areola, 2018). Everything is raw and erogenous, pleasure and urge, beyond the question of viewer and viewed, desired and desiring. The painted body embraces the body of the audience, the ecstasy is shared and generous. “I situate art not in reality but in relation to desire,” says Dumas. “My best works are erotic displays of mental confusion (with intrusions of irrelevant information).”

She uses photos to start a painting: personal snaps of her husband or children, Polaroids, press shots representing a migrant or a scene in the Middle East, images from porn. “I use second-hand images and first-hand emotions.” A small boy greets a crowd (Child Waving, 2010), an image from the Iraq War. He’s waving to soldiers, but is he friend or foe? Each image embraces the relativity of truth and the question of good and evil with the same power – the body becomes the embodiment of all moral and abstract issues. But perhaps the most important source of Dumas’s work is her passion for poetry. This is celebrated in the exhibition through figures such as Pier Paolo Pasolini, Jean Genet (“Anyone who has not experienced the ecstasy of betrayal knows nothing of ecstasy at all”), Oscar Wilde and especially Charles Baudelaire. “Poetry is writing that breathes and jumps and leaves spaces open, so we can read between the lines,” Dumas explains. If we accept this definition, she is surely one of the greatest poets of our century.

Marlene Dumas, “Open-end”, until January 8, 2023 at Palazzo Grassi, Venice.