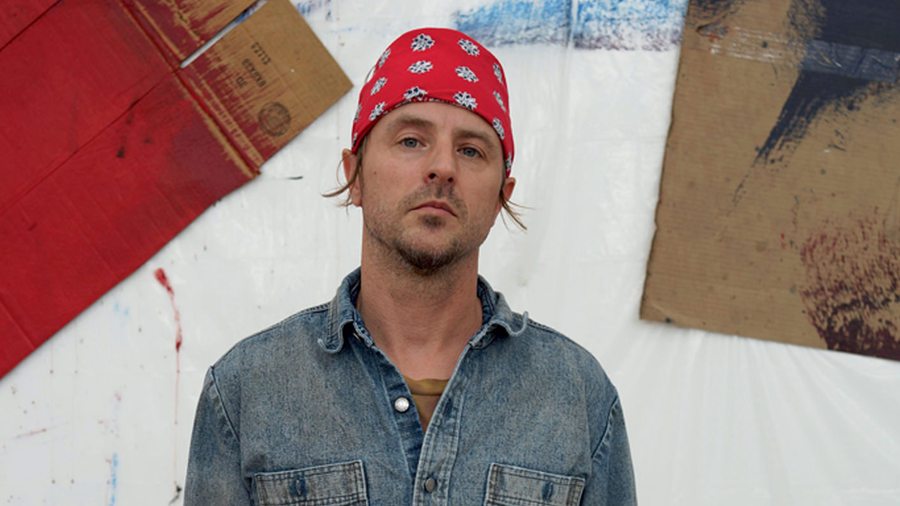

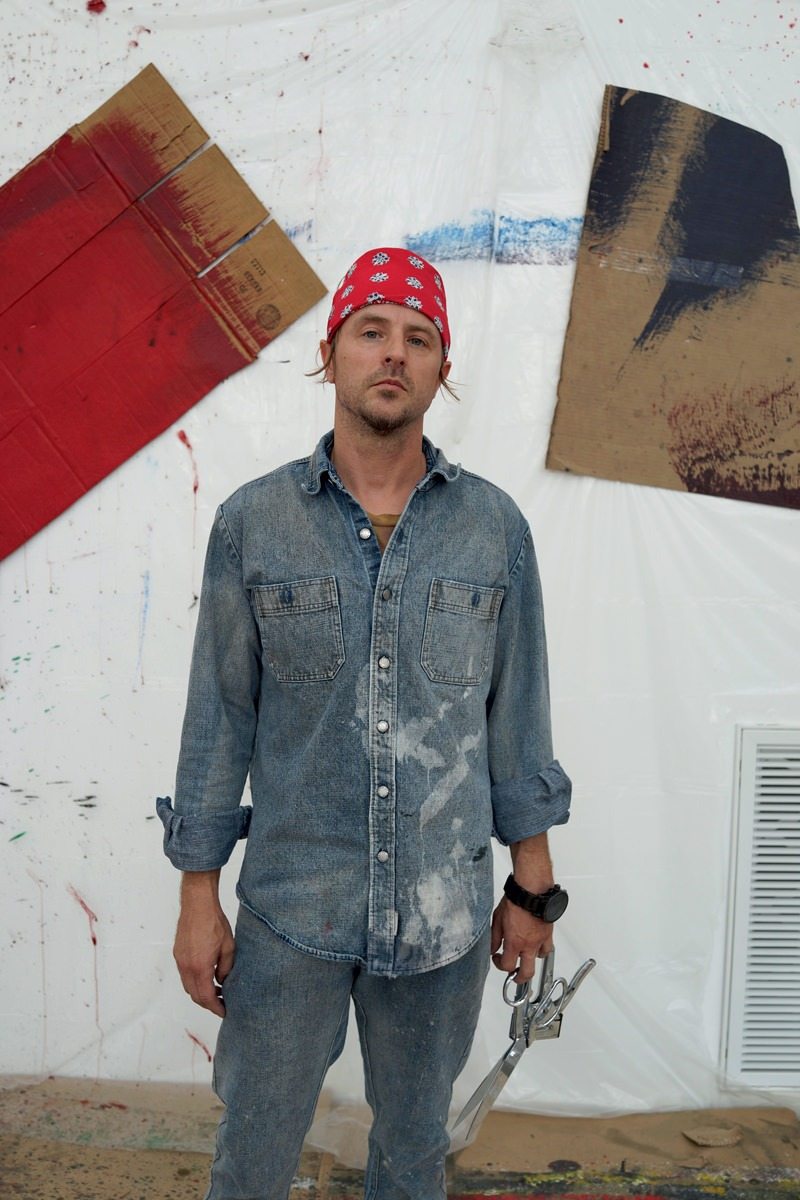

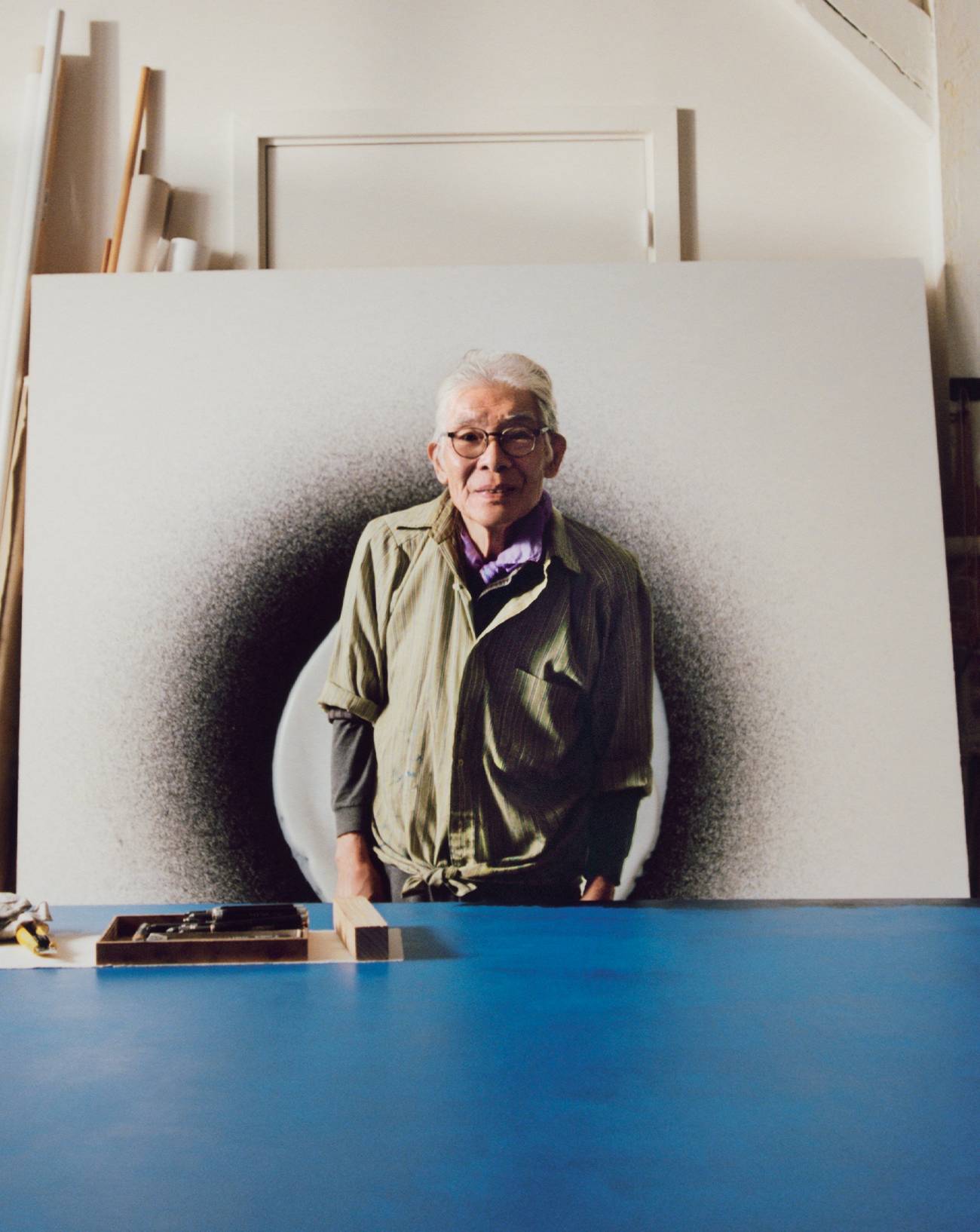

This October, Sterling Ruby will be showing simultaneously in three Parisian locations during FIAC: the two Gagosian Gallery spaces, as well as the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature in the Marais. Probably one of the most ambitious artists of his generation, Ruby is a polymath who likes to try out every possible technique and medium: painting, ceramic, sculpture (in both epoxy and bronze), collage, drawing, textile, video and even fashion, as evidenced by the menswear collection he designed with Raf Simons. Born in 1972 at an American army base in Bitburg, Germany, to an American father and a Dutch mother, he currently lives in Los Angeles where he runs one of the largest artist’s studios in the city. His work is concerned with many themes, penchants and ideas, among them urban sociology, art history, social constraints, architecture, graffiti, minimalism and craftsmanship. The new pieces he will be showing in the Gagosian’s Le Bourget space are monumental ready-mades comprising parts of U.S.-navy submarines, while in the Rue de Ponthieu space he’ll be exhibiting new paintings made using the technique of frottage, in contrast to his usual spray-paint work. Finally, at the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Ruby will create an installation of giant functioning woodstoves in the courtyard. Numéro caught up with him just after his move to new premises in downtown Los Angeles.

Numéro: Can you tell us about your background and career?

Sterling Ruby: I was born in Germany, but we only lived very briefly in Europe before moving to the States, first to Baltimore, and then to the small town of New Freedom, Pennsylvania.

I grew up on a farm, but I spent my teens going to either Baltimore or Washington, D.C., trying to avoid this rural setting by seeing three or four bands a week. I studied art in Lancaster, PA, Chicago and Los Angeles. Early on I studied life drawing, still life and landscape painting. At the Video Data Bank in Chicago, I basically watched every art video and artist interview that they have in their collection. I studied cult psychology, minimalism, colour theory, French philosophy and Postmodernism. I studied under Sylvère Lotringer, Laurence Rickels, Mike Kelley, Richard Hawkins and Diana Thater at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena.

How did your background shape your identity and taste?

The area in Pennsylvania where I grew up was rural and working class rather than intellectual. I was always pushing against a small-town mentality. I pursued creative culture wherever I could find it. I felt it was absolutely necessary to get out of there, but over time I’ve come to realize that a lot of my interests and perhaps even my aesthetics come directly from that time in my life.

What were your artistic references?

I recognized the value in crafts before I understood art. I saw Amish quilt making and craft before I saw or understood any modern or contemporary art. My family’s dishes were Pennsylvania redware ceramic, so again, there was that craft aesthetic. My first major contemporary influence, or moment, was seeing the Bruce Nauman survey at MoMA in 1995. He continues to be one of my favourites. My favourite art-historical moment is the Bauhaus movement. It shook things up from a utilitarian versus a non-utilitarian perspective, it challenged craft to be high art and vice versa. I often remind myself that this period produced some of the most influential art for me.

You’re known for working in many different media − drawing, painting, sculpture, but also textile and clay. Which do you feel most at ease in?

I like working to solve the problems inherent within a specific medium, and sometimes pushing it out of its usual contexts, but then I also like to be able to use a medium in a fairly traditional way. I like to switch it up. It’s part of my schizophrenia, the impulse to move through materials as well as gestures.

The notion of craft is very important in your work. Do you make all your pieces yourself?

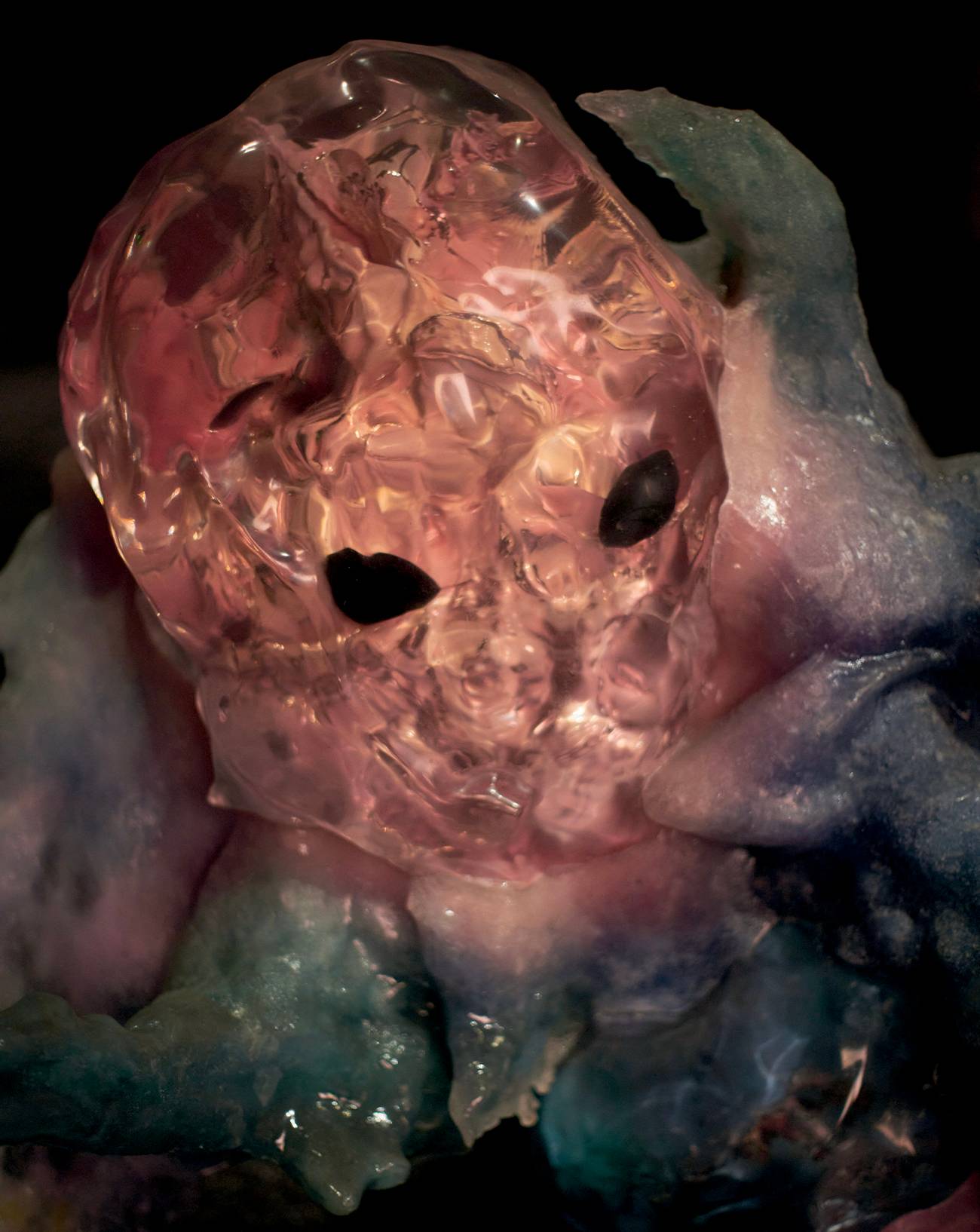

The ceramics are definitely a good example of how I work with materials. I’ve been making ceramics for 15 years now, and I’ve figured out how to force the limits of the firing and glazing process. Maybe a by-the-book ceramicist would see my work as naive, primitive or even amateur, but after so many years I have a solid knowledge regarding what clay to use, how much grog I prefer, how much a work will shrink, what the bricks and elements in a kiln do, how best to utilize convection and air circulation during firing, how cone temperatures affect glaze colours and how, no matter what technical expertise I think I may have, certain works will inevitably blow up. My background is very foundational: I was taught that in order to use materials you must first know their properties. There are still certain things, like bronze casting, that I can’t or don’t want to do in the studio.

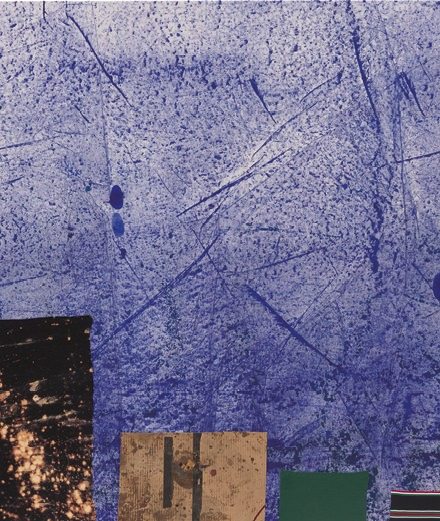

Your paintings are both abstract and also somehow figurative, with landscapes, horizons, sunsets…

There’s a lot packed into those paintings. I started to make them as a direct reaction to seeing graffiti and gang tags in my neighbourhood and near my studio. But also there are horizon lines because I tend to paint that way, from left to right and from right to left, side to side. Los Angeles has these amazing sunrises and sunsets that transform the urban sprawl into a meditative plane. I also think about the paintings cinematically. For example Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou: the cutting of the eye, the slicing through a frame, the formal creation of a landscape…

And what about your work with textiles?

My use of textiles has come full circle in a certain sense. I was initially bleaching and dyeing fabric at the studio to make soft sculptures. I would then keep the remnants and scraps that I found particularly compelling, and I used them to start making clothes. Then I began a series of collaged fabric works. I was thinking about them as quilts, like the Amish quilts I saw growing up, and then Gee’s Bend [an African-American community in Alabama] quilts and Japanese boro textiles also became an influence. I thought about the context of quilt making, the ritual of production. These work clothes that would get too worn out to continue wearing would be turned into beautiful blankets and quilts. The quilters would transform this utilitarian material into an aesthetic material. My quilts started to get larger and larger, so in my mind they shifted into flags, tapestries or backdrops – I thought about the history of bands travelling with their backdrops, I thought about touring-theatre sets. I construct them in the same way I work on a collage, choosing from piles of hand-dyed, bleached and sewn remnants. The only real difference between working on the flags as opposed to a paper collage is that, because the scale is so much bigger, I have to view and arrange them aerially from a cage on a forklift.

You’ve always been interested in clothing, and have long made your own work clothes. Recently you designed a collection with Raf Simons.

My mother gave me a sewing machine when I was 13. I liked the autonomy of making my own stuff. I was definitely not making couture garments at that time, what I made was rough looking, punk. Raf is a close friend, and it’s easy to collaborate with him. We’ve worked on a denim line, I designed his Tokyo store, he worked my paintings into his first couture line for Dior. During his visits to the studio, he would see the work clothes I made for myself, and that prompted him to suggest we work on a men’s line together. We showed it in Paris last year for the winter season. It’s very liberating for me now to have a section in the studio that’s solely dedicated to garment production.

This autumn you’ll be showing in Paris for the first time with three large-scale exhibitions. What are the ideas behind these shows?

I always make new work for gallery exhibitions. The notion of space and work is at the heart of all my exhibitions. Where is the space located? What city? What country? What is the architecture of the space, the light of the space, ceiling height, what kind of floors? What will be the context for the work and what are the parameters of its installation? These are all questions that I think about when developing a show or a new body of work. I don’t work well using models or 3D renderings, I like to physically push things around in a space. The install time for an exhibition is an exercise in troubleshooting. I move things around and do multiple hangs. For the past couple of months I’ve had Gagosian’s Le Bourget and Rue de Ponthieu galleries taped off on the floor of my studio − I’ve been walking through the square footage, each level and each room of these spaces, for months now. I was also very into the idea of using both of the Gagosian Paris spaces at the same time. Le Bourget is a large space, so sculptures that have been installed in my studio over the past year will relocate to a large hangar in Paris, alongside large bleached-fabric flags, and I’m showing a new group of paintings at the more intimate space in town. For the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, a set of four oversized stoves, based on cast-iron farm stoves, will be installed in the courtyard. Fires will burn in the stoves. I like the ritual of it.

And what about your new metal sculptures and their relation to submarines?

I’ve been working on a new studio building for three years now. We finally moved in this year. The new studio is right down the street from the old studio, in Vernon, an industrial zone just ten minutes from downtown Los Angeles. Driving back and forth between the two buildings, I would go past this huge lot where demo crews were chopping up truck-sized chunks of metal. One day I stopped to see what they were doing. This company had a contract to dismantle and scrap de-accessioned U.S. submarines. I eventually struck up a deal with the owner of the company, and I was able to acquire some large cut-up fragments of these submarines. At the time I didn’t know what I was going to do with them, but I knew that they had this potency. These large pieces of metal that were being delivered to the studio looked so abstract, so foreign. The studio lot starting looking like a massive military-machinery graveyard. I began merging these scrapped and chopped-up pieces from the submarines with automobile-engine blocks and industrial pipes as a way of creating a new kind of evolutionary and monumental sculpture. I see it as a kind of “dragging” process, pulling things out of the ocean and bringing them onto land, a transformation or mutation of previous sculptural forms into new hybrids.

You often come up with rather cryptic titles for your exhibitions, such as DROPPA BLOCKA, CHRON, EXHM or BC RIPS, to cite just a few. Where do these come from?

Titling is an obsession of mine. I have a particular interest in codes and acronyms. CHRON is short for chronology, Exhm for exhumation. I’ve been reading about this aviation phenomenon called graveyard spin, which is when a pilot loses his perception of direction. That title idea has generated an entirely new body of work. There’s this online chat site where drug addicts go to discuss various drug combinations. They give their mixes invented names depending on what kind of high they get from their concoctions, and they often refer to a system of colour-coding references, taken from the Marquis reagent drug-testing kit used by police officers to detect narcotics. There was a complete system of alchemy and hermeticism contained within this coding, and I used this language to title many of the ceramic basins. I use scientific, medical, archaeological, prison and drug terminology in ways that alter the original meanings, disassociating the meaning while still maintaining the original reference. Sometimes I want a title to be a graphic. I type lists, names and words onto my computer screen in all caps and a sans-serif font as a way to start looking at them as pure graphics, design and form.

Your new premises in Los Angeles are now the biggest artist’s workshop in the whole city. How do you go about juggling all your many projects and managing such a big team?

It’s different in the new studio. The space is definitely bigger, which is offering me room to work in solitude. I actually feel like I’m becoming less of a manager. I’ve had a similar-sized team for a few years now − ten full-time employees. Many of them have been with me for a very long time, and I trust them to run the day-to-day operations

and logistics. They free up more time for me in the studio, and make many decisions on my behalf so that I can get on and focus on the work itself.

Sterling Ruby exhibitions: PARIS at the two Gagosian Gallery sites: 26, avenue de l’Europe, Paris-Le Bourget, 18 October–19 December, and 4, rue de Ponthieu, Paris 8th, 21 October–19 December, www.gagosian.com; STOVES at the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, 62, rue des Archives, Paris 3rd, from 21 October–14 February, www.chassenature.org.