Evgenia Citkowitz: There’s always been a performative aspect to your work. In your student days you would wrestle and dive into clay, which was the main event. Now this might be a ritual part of your process, but it isn’t necessarily apparent in the finished work.

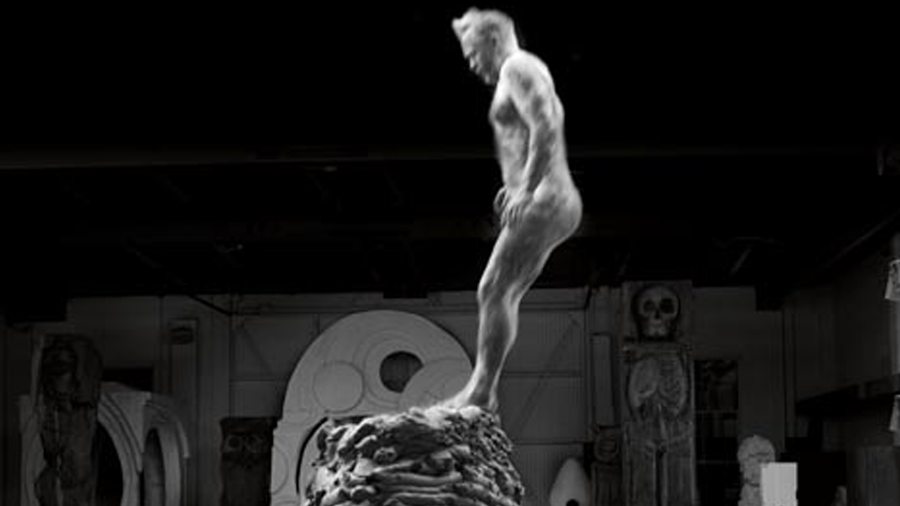

Thomas Houseago: My first real artworks, made at Jacob Kramer College of Art in Leeds when I was 18 or 19, were actually performances. During them, through certain actions such as burning things, jumping on things, or covering myself in things, things and objects would often end up being being made, so those were the kind of acts that needed objects, that needed materials. At that time, I saw my body as very much part of the material. My first sculptures were leftovers, if you like, from performances, and as time went on, when I went to London, in 1991, I became more interested in freestyling sculptures, and the idea that performance was an action needed to make them kind of moved into the background, but was always still there. Once in L.A., I completely lost myself to the sculptural object. I almost lost track of my body in that process, and my action was pretty much just the compulsive making of objects.

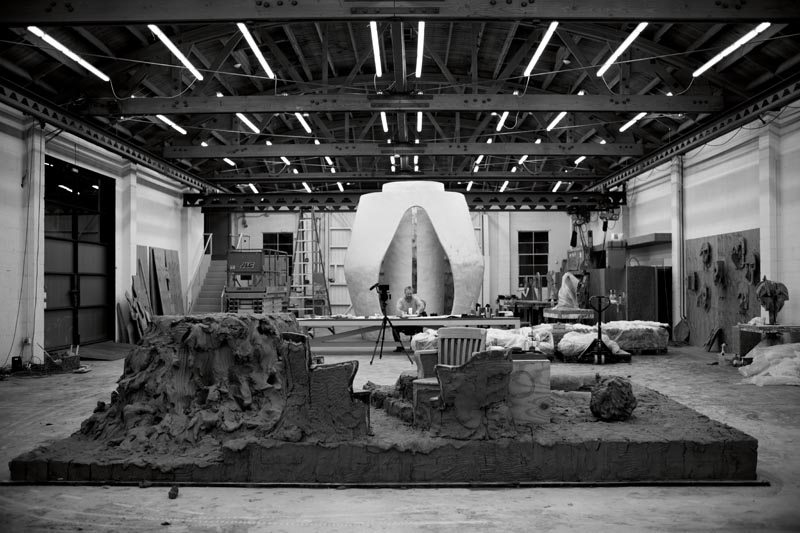

Your sculpture Cast Studio, which is being shown in Paris, evokes a primeval landscape that’s also prototheatre: ossified chairs wait for visitors; a gnarled mesa rises to form a stage; a dug-out trench could be a fort, a place of rest or of committal. Your partner, Muna El Fituri, has documented your process in a remarkable series of photographs and films where you fall, grapple, ease and pound the clay into submission. Could you tell me about the origins of Cast Studio?

It represents a return, and at the same time a move forward. Its roots are in my earliest experiences with materials: playing in the sandpit, finding clay and mud, making objects. In many ways the piece represents a kind of regression, but at the same time it’s about what’s happening in my life now. My collaboration with Muna is much more fully realized in this piece. When we first met, we worked closely together and began really looking at each other, looking at what we were doing. I became interested again in the actions around the objects, and in the nature of the studio – the people who came by, the way I work, the kind of actions needed to make it work. So in many ways, the idea of filming and photographing the making of the sculpture, which ended up being the final piece, was the result of the conversations that Muna and I had had for many years, about the fact that Muna was making her own photographs in the studio, and she was watching and documenting me, and we were discussing where the work came from, certain obsessions and mannerisms. To some extent, Cast Studio evolved out of these discussions. The piece embodies my current ideas about sculpture and how it interacts with viewers, with people, with an audience, that a sculpture is a forum for other things; it’s a reflection of a larger idea of a studio, what I want my studio to be – a kind of community that is in my life now that is part of the studio. It’s also processing things that came up in my own somatic experiences.

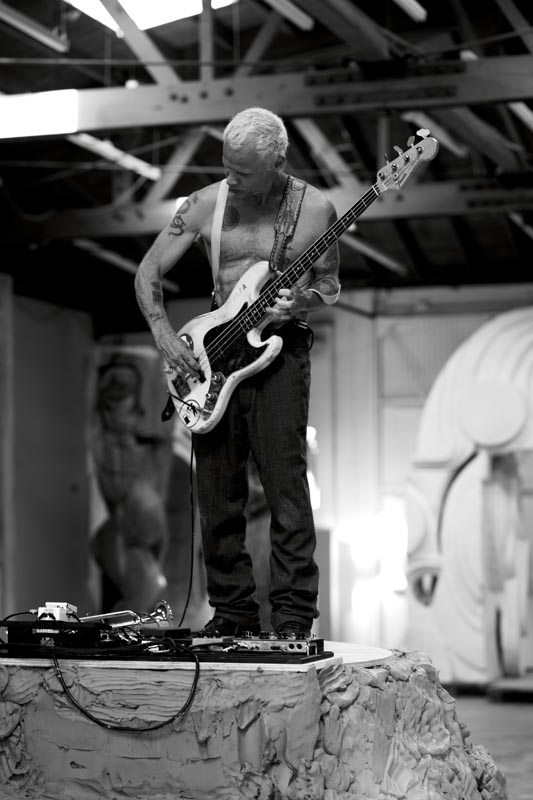

For Cast Studio you enlisted your family [Abe and Bea Houseago] and your friends [the artists Karon Davis, David Hockney, J.P. Gonçalves de Lima, Lorna Simpson, Marco Perego, the filmmaker Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, the curators and museum directors Caroline Bourgeois, Fabrice Hergott, Olivia Gaultier-Jeanroy, Michael Govan, the musicians Flea, Kamasi and Rickey Washington, Arrietta Woods, the actors Brad Pitt, Zoe Saldana, Julian Sands, the poet Robin Coste Lewis, the lawyer Christiane Asschenfeldt] to respond to the piece.

Pretty quickly, as I progressed with Muna open-endedly photographing and filming, I started to review the photographs, and I saw that those images were powerful and had so many references and so much resonance. And so the images began to push and lead the piece, and I began to act, sometimes in ways where I was responding to the images that Muna had made. There were times when Muna was directing me, and there were times when I was directing Muna to photograph me a certain way. It started to become clear that all these roles – artist and model, director and actor, viewer and viewed, moments of real intimacy and moments of conscious acting, moments of labor (the literal physical action of making the piece) were part of the work itself. Once that started to happen, I began to realize that, yes my body was really important, and, yes the actions I was doing were central to it, but the piece began, in a weird way, to take over. That really started when Karon Davis came by with her son, Moses, and Moses intuitively and impulsively jumped into the piece and began to do a lot of the things I had been doing earlier in the making of it. He wanted to bury himself. He wanted to leap off the stage. That I think represented the full crossover moment when I understood that the piece would become more than me just acting in it, and more than just my body, and more than just my dynamic with Muna. So at that moment, I slowly began to move away from the notion of being the sole author, the sole performer. Earlier that year I’d had this image where the one person I really imagined acting in the piece was Julian [Sands]. I’d been struck by Julian in a film about Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty [a piece of land art from 1970], where he’s reading and walking on it. I also like Julian’s physicality and his being a Yorkshire man, like me – he comes from a similar place, but his creative energy flows in a different way. Once my friend’s son had “performed” in the piece, I quickly moved to wanting Julian to come in, and once that had happened, I realized that that performer, the person who comes in, transforms, changes, leaves an impression on, or affects the meaning of, the work, and there was something unbelievably moving about that idea – the sculpture could be more than just this object, more than just Muna’s film or photographs, and expand out into being the studio – our friends, people that performed. I wanted to show that sculpture, music, poetry, performance and all these different things could align, and that they could embrace one another, in a sense, to become something rich and, in a certain way, unique.

Thomas Houseago, Almost Human, until July 14, musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, France.