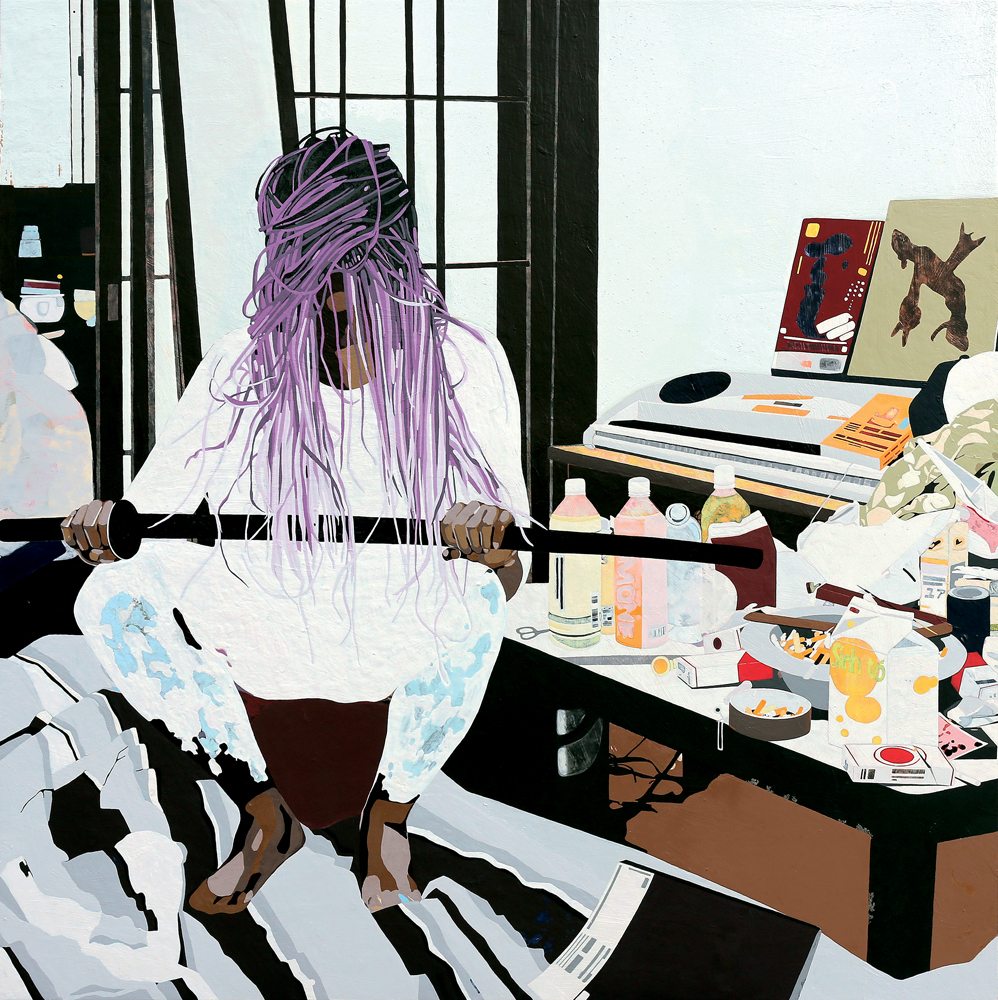

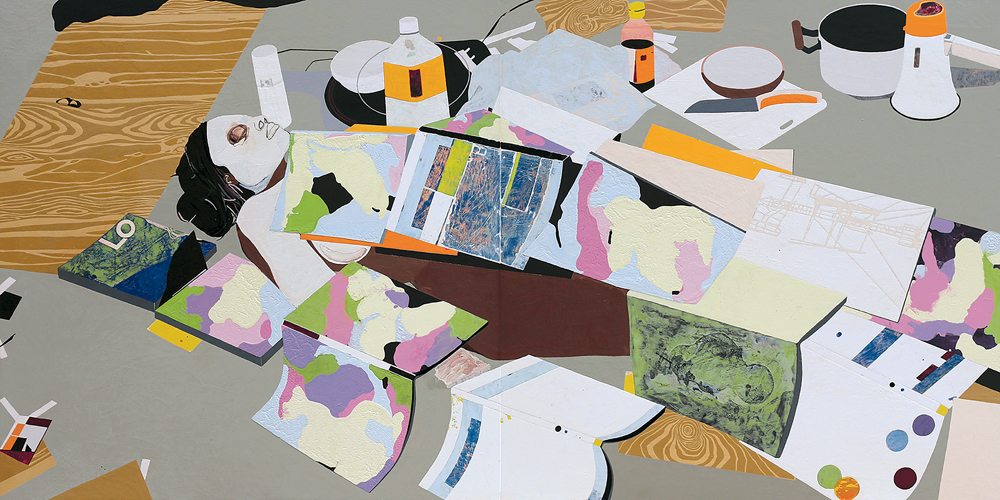

In addition to their materiality that beckons the viewer in for a closer look, Ymane Chabi-Gara’s paintings deploy a soft pastel palette that contrasts with the disturbing nature of what they depict. Her recent works show Japanese hikikomoris – young people, mostly boys, suffering from so- cial withdrawal so acute that they shut themselves away in their bedrooms. Chabi-Gara’s interest in Japanese culture, and Tokyo punk in particular, goes back several years. On returning from a six-month residency in Japan during her studies at Paris’s École des Beaux-Arts, she began collecting images of hikikomoris she found on the Internet. It was also during this trip that she discovered butoh, whose movements and gestures left a lasting impression on her. Her subjects often have smooth faces, lowered eyelids and sometimes blank white pupils like antique statues.

In her early works, Chabi-Gara herself could often be recognized, as though reincarnated as a hikikomori, self-portraits that weren’t en- tirely that but were perhaps a way of claiming these spaces by adding a few personal objects to her compositions. In her recent paintings, she portrays herself less and less, instead depicting the colourful sensations that her characters create. In general, she doesn’t paint their gazes, a way of not immo- bilizing her compositions and of referring us (and herself) to questions of form and materiality in painting.

As a child growing up in the Paris suburb of Fontenay-sous-Bois, in a family little interested in art, Chabi-Gara dreamed of becoming an illustrator. A secondary-school teacher helped her prepare for the entrance exam to the École des Beaux-Arts. Her first artistic shock was Matthew Barney’s The Cremaster Cycle at Paris’s Musée d’Art Moderne (2002), a reference that chimes with her taste for displaying bodies, and with the way she blends the violence of her themes with the softness of pastel colors. Not to mention her interest in music – a guitarist and pianist in a group, she hesitated be- tween studying art and music (she only went to see Barney’s show because he was Björk’s boyfriend), but eventually understood that the one thing she wanted to do was paint.

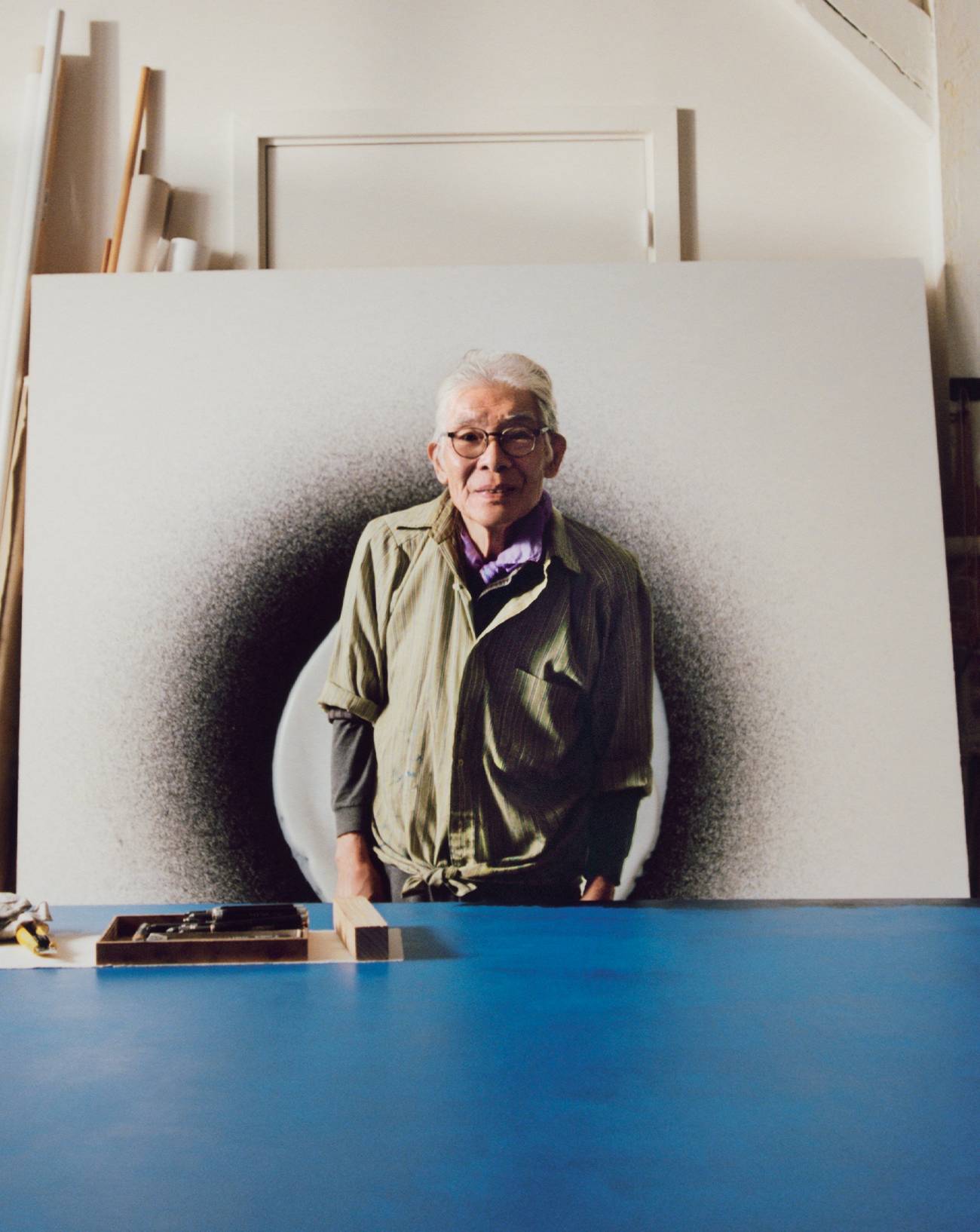

Chabi-Gara is happy to discuss the sense of isolation she has felt at different times in her life, moments of extreme loneliness that only painting seems to have saved her from. She translates these states of obsession with great precision in her images, working non-stop from dawn to dusk in her studio on the outskirts of Paris. Located in a quiet neighbour- hood, sandwiched between 18th-century buildings and abandoned factories, it contains few objects inside. Just like her home, she says, because her needs are few. The contrast with her paintings is striking, because they abound with ob- jects, like the bedrooms of the hikikomoris or the Japanese thrift stores she also draws inspiration from, where sec- ond-hand clothes pile up to the point of suffocation.

She translates these states of obsession with great precision in her images, working non-stop from dawn to dusk.

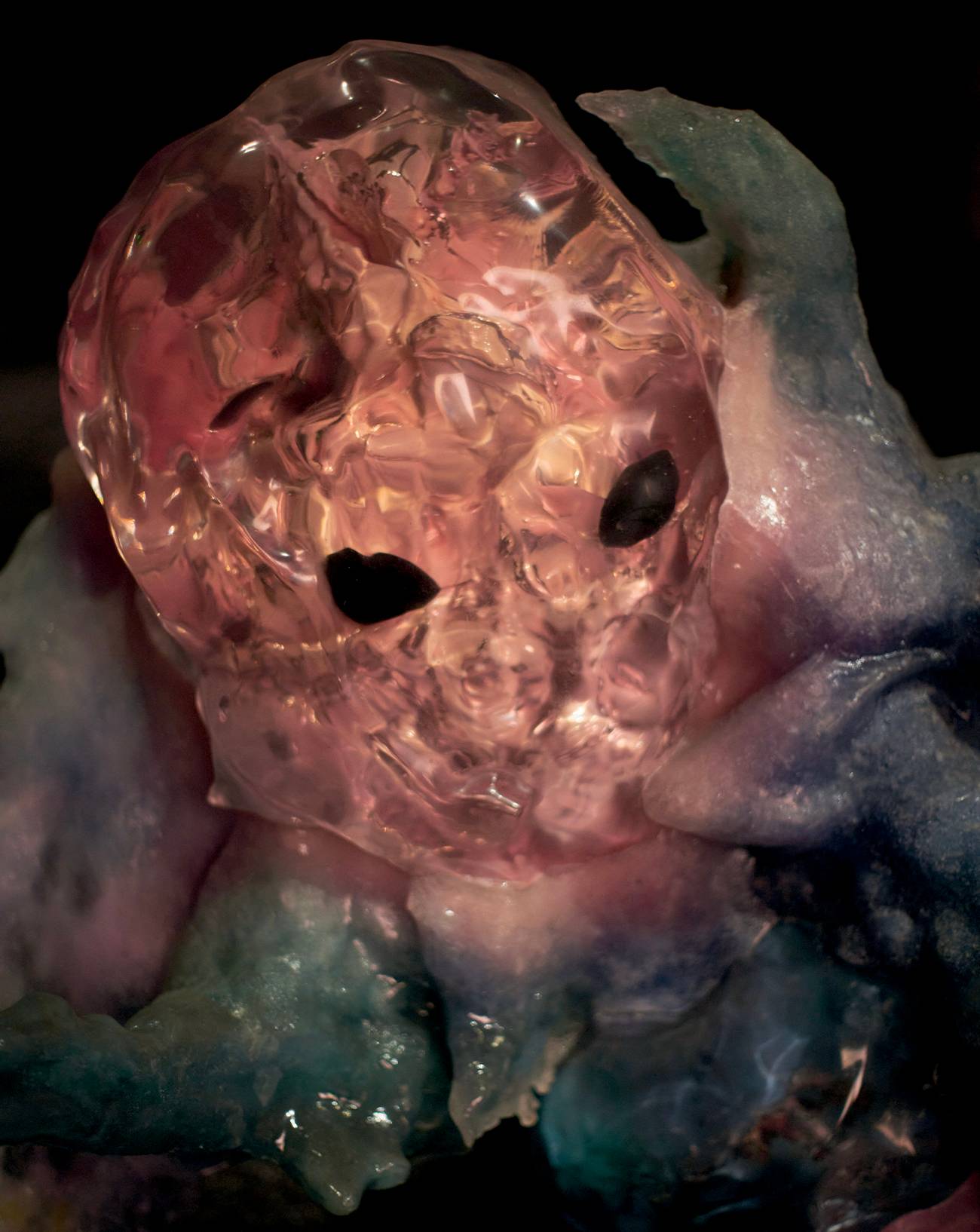

On a shelf are books she has recently perused, including a monograph on David Hockney and a volume on Alice Neel. She discusses her interest in Marc Desgrandchamp, who was her teacher at the École des Beaux-Arts, and how she admires the tension he creates between a certain romantic gentleness and a gnawing harshness. She likes Gisèle Vienne’s raw dance and grating sculptures, as well as Katharina Grosse’s painted immersive environments. Several works hang on her studio walls, including a small stork made at a centre for the disabled near Glasgow – an interest in art brut that also chimes with her obsessions.

Chabi-Gara works slowly and precisely, only taking decisions after long hours spent observing her paintings. A few tests on large canvases led her to prefer plywood boards glued to the chassis, because her layers of paint were so thick they wouldn’t adhere to the fabric. Her works are almost always large formats, which allows her to paint her characters life- size. First she prepares the surface with opulent layers of gesso, sometimes using the contents of old dry paint pots as thickening, or working over the top of rejected paintings. She then applies a diluted wash, generally an uneven mix of pink and yellow, but more recently a combination of different blues. Once it has dried, she draws directly onto it, trans- posing her source images with a very precise grid technique – “the only way to escape from it aferwards,” she says. Which means there are no preparatory drawings, although she is thinking of showing some of her pre-paint large-scale draw- ings just as they are in the months to come.

She has never been attracted to oil paint, but loves to play with degrees of dilution, the thickness of the paint, and the number of layers she applies to her boards.

Finally comes the moment of painting itself, the composition evolving as she takes successive formal decisions during long hours of concentration and delight. A small piece of furniture disappears, a book or a CD is added. She works with different kinds of paint: acrylic lacquer, whose brilliance contrasts with more matte paints, as well as satin finishes, and leaves certain areas untouched so that the coloured washes of the preparation come through. She has never been attracted to oil paint, but loves to play with degrees of dilution, the thickness of the paint, and the number of layers she applies to her boards. As she does so, the subjects of her paintings, their dizzying sense of space and the different stories one might invent on seeing them disappear into the materiality of the paint.

On a table, a few small panels are in the process of preparation, blank surfaces for reduced-format paintings that she produces alongside her large-scale works. They are almost always abstract, completed in a single day and inspired by fragments from her bigger works. These excerpts become almost illegible, with colour and materiality running at full blast. Her next avenue of exploration perhaps?

Ymane Chabi-Gara's works has been presented during the exhibition Des Corps Libres – Une jeune scène française, Studio des Acacias, Paris, from May 5th-28th. She is represented by Kamel Mennour gallery.