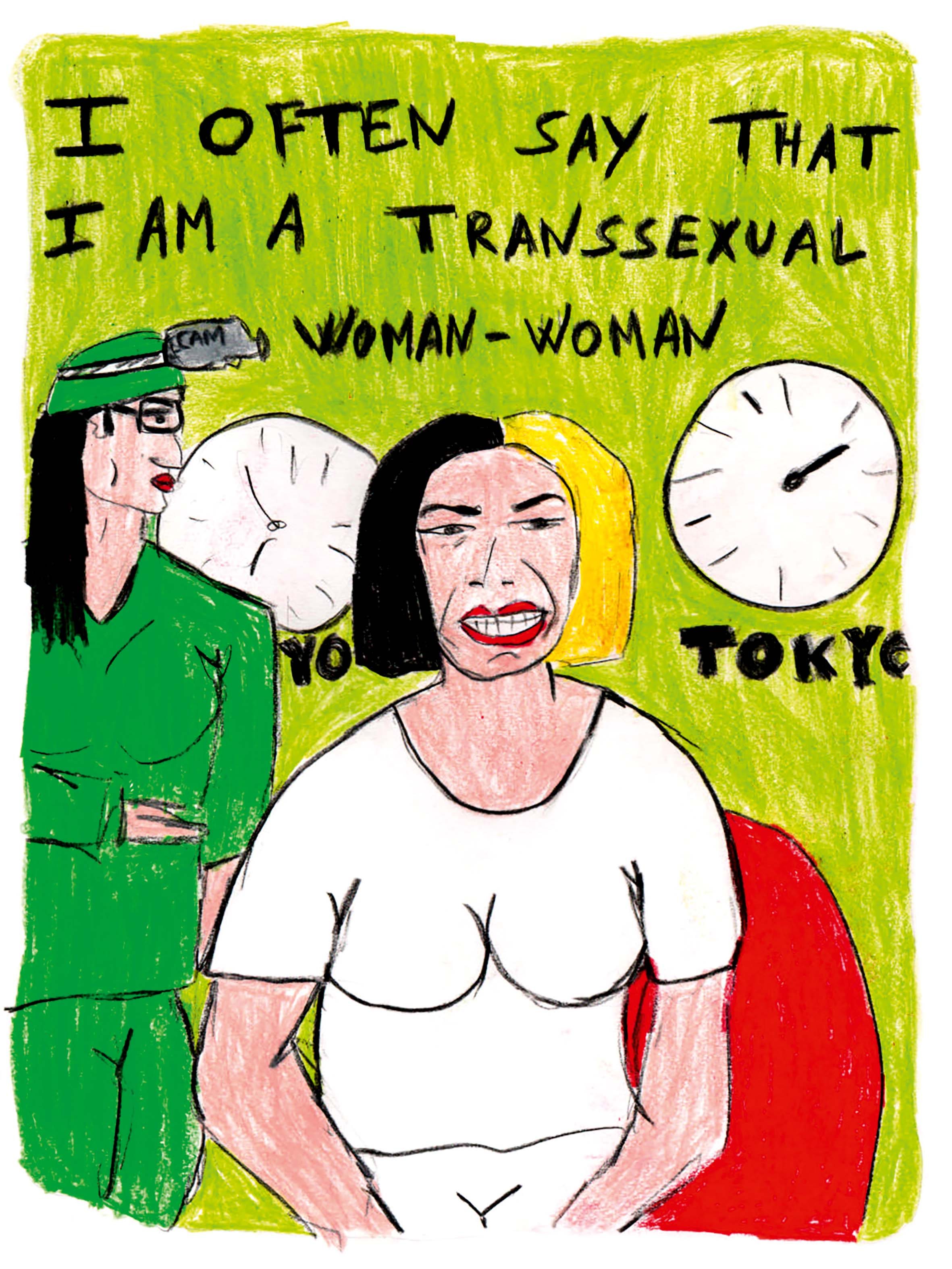

In each, she had her face retouched – her mouth to resemble François Boucher’s portrayal of Europa in L’Enlèvement d’Europe; her chin to look Botticelli’s depiction of the goddess of love in The Birth of Venus; her forehead and eyebrows to mimic that most iconic art figure of all, Leonardo da Vinci’s Monna Lisa. This self-branding with the canons of art history was not, as is usually the case with plastic surgery, an attempt to make herself look more “beautiful,” but rather a gauntlet thrown down against the canons of beauty in our era. Carefully staged and costumed, each operation-performance was filmed and photographed, not with a documentary goal in mind but as products of her surgical happenings. “Every image of me is pseudo,” as she explained, “be it carnal, verbal, medical, scientific or biological. For me, what counts is circling around these possible images, which are always worryingly strange, and pushing them, fumblingly, always astonished by the vision of what could be myself. My work is a host of images of myself, a myriad of photos, a flow, a haemorrhage, a dysentry of images, a beginning of a proof of my incarnation.”