Numéro Homme: So, darling, how’s it going at Dior?

Kim Jones: Really well! I love it! It’s great. Very different to Louis Vuitton, because Dior – as opposed to a trunk-maker and manufacturer of leather goods – is a ready-to-wear fashion house with its own workshop. Here, everything moves very quickly; the archives are incredible. But I’ve only been working for the house for a little over a year, so for the moment, I have mainly focused on Christian Dior: what he did, what his life was like... He was a fashion designer, obviously, as well as a gallery owner, a collector, a nature lover… All these things that he and I actually have in common.

How on earth did you manage to pull off your collections at Louis Vuitton without a workshop at your disposal?

For each collection, we started with pictures of about 100 trunks and step by step retraced the journey they took, before embarking on our own travels to find inspiration and gather information. We then returned to Paris to design the collection. We also delved into the maison’s archives, so as to draw on the past and try to combine it with the present to come up with something new.

OK, but how did you make the clothes without the help of any ‘petites mains’?

The clothes were made at a factory, then sent to us in Paris for the final adjustments. When I was at Louis Vuitton, I designed 12 collections per year, so didn’t exactly have time to go around the manufacturers. But when you work for a company as influential as Louis Vuitton, your contacts tend to show some flexibility.

At Dior, are the workshops used for the men’s collections the same as those used for the women’s ready-to-wear and couture collections?

No, there are three separate workshops: one for haute couture, one for women’s ready-to-wear and another one for menswear, ours, which is in the same building as the studio, downstairs, making things much easier and smoother. That being said, I knew exactly what to expect when signing with Dior, considering that at the time, a handful of other luxury labels had offered me the role of artistic director…

Which ones?

I am not going to tell you anything else about that, but I’m sure you know perfectly well. The fact of the matter is that I had dinner with Mr Arnault [Bernard Arnault, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of LVMH] and Pietro [Pietro Beccari, Chairman and CEO of Christian Dior Couture]. They told me that they hoped that I would join the Maison. I like Mr Arnault very much – he’s someone who understands the product very well – and I’ve known Pietro for many years, as he is one of the people who recruited me at Vuitton. It’s incredibly easy to work with him, because he is very straightforward and direct. If he doesn’t like a piece or feels that something doesn’t work, he just tells me without beating around the bush. It was a completely natural choice for me.

Aren’t the meetings with Mr Arnault scary? Personally, I think I think I would be scared out of my wits.

I think he is just fascinating. I love showing him my work, and I’m always excited to see his reaction. Let’s be realistic – he’s seen everything there is to see, so if he is enthusiastic about something I show him, that’s really very positive for me. There are two other creative directors at Dior. And Hedi [Slimane] does his thing at Celine, Kris [Van Assche] at Berluti… So, in my work, I am not going to introduce a reference to what my predecessors have done. In any case, the ultimate reference is Christian Dior, no one else.

Is it easier to work for a Maison like Dior with an illustrious heritage in ready-to-wear, or to write a new chapter in the history of a Maison like Louis Vuitton?

At Vuitton, my collections were steeped in the history of the Maison, but they were also influenced by travel. Louis Vuitton is first and foremost a brand built around the art of travel. During the years I spent there as Creative Director, I paid very close attention to sales figures, which I saw improve dramatically. Personally, I rely on facts and figures above all. Having said that, I had been working for the same Maison for seven years and was being offered a lot of other opportunities – you know what they say about the seven-year itch… I felt that the time had come for me to move on to something else, to get out of my comfort zone.

During your time at Louis Vuitton, was it you that set up the collaboration – which was a tremendous success – with the New York streetwear brand Supreme?

In fact, what happened was that Michael Burke contacted me – he’s a very good friend, as well as being the Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Louis Vuitton – to ask for the phone number of James Jebbia [the founder of Supreme]. I replied: “I’ll give you his number if I’m allowed to launch a partnership with him.” In a way, I was returning a favour, because my first job in fashion was at the Gimme Five store in London, where I unpacked boxes from Supreme. I was 19 years old; I was still a student at the time, and the Supreme brand had just been launched. So it was great to see things come full circle at Louis Vuitton. I think that’s what gave our collaboration such an authentic quality, because of my longstanding relationship with James Jebbia. It also helped completely resolve any enduring tensions, because there had been a dispute a few years earlier between Supreme and Louis Vuitton – things had even gone as far as a lawsuit. So it was cool to be able to turn the page and say that none of that mattered anymore! We always make such a fuss about the new love story between men’s fashion and streetwear, but in reality, what’s most important is to get the best to work with the best. Men’s fashion has changed so much. Frankly, just look at us: you are the editor-in-chief of a men’s magazine and I am the creative director of menswear collections at Dior, and we are both in shorts and T-shirts. And yet nobody could say that we don’t know how to dress!

You said earlier that you were interested in facts and figures… How did the collaboration between Louis Vuitton and Supreme translate into sales?

I’m not allowed to give you the figures, but what I can tell you is that the whole collection sold out in a single day, and the prices were absolutely crazy. I must say that what we are doing here [at Dior] is also selling very, very well. The business is growing fast, which is great, and it’s cool to see all of this happening in such a short time. At Dior, I have launched collaborations with contemporary artists in a nod to Christian Dior’s own activities as a gallery owner. As it happened, he was not allowed to use the family name for his gallery, his parents not willing to see him lower himself to the position of “shopkeeper” – even though he was working with painters like Picasso, Dalí, and Max Ernst at the time. I think that the younger generations have a real passion for this kind of approach. For my part, I have always loved contemporary art, of which I am an avid collector.

What has happened to the imposing statue that you ordered from the artist Hajime Sorayama for the Autumn-Winter 2019-2020 pre-collection catwalk show in Tokyo?

It’s still standing tall somewhere, but don’t ask me where.

To what extent does a designer today need to take into account the demands of marketing teams in order to build their collection – in particular at large fashion houses such as Dior or Louis Vuitton?

Let’s say that the answer has two parts. When I create very personal things, they generally sell very well. That doesn’t mean that I don’t listen to the marketing people, but let’s not forget that I come from a very commercial background as I used to work for Louis Vuitton, the flagship of the LVMH group in terms of sales. In short, I know what customers want. The debate that pits art against business is interesting but, as a whole, I tend to follow my instinct, which drives me to do exactly what I want, when I want. But occasionally Pietro might call me to say, “I’ve thought of something”, and I say, “Great, let’s do it!” because I find his idea really exciting. I love a challenge, and I love to go off the beaten track. I’m no diva, and I don’t have a tantrum when something isn’t done how I’d like it to be – because that kind of behaviour is no longer tolerated in this day and age.

For a Londoner born and bred like you, is it easy to adapt to the Parisian lifestyle?

I went back to London! One of the conditions of my contract at Dior was that the studio would be relocated. I think I showed what I’m made of at Vuitton, in terms of creativity and sales, and I work pretty well as part of a team, but there’s a huge difference between London and Paris. London is a very open-minded city, whereas I find Paris quite compartmentalised.

How so?

In London, you can go out to dinner with someone who’s 7 or 77, with a managing director or a binman, and it makes no difference. I find that way of looking at things very inspiring, and I don’t think it’s very common in Paris.

Do you speak French at all?

I speak it, but only when I want to. It’s my secret weapon: I can understand everything people are saying, without them realising. [Laughs].

Did you know you were going to end up at Dior when you left Louis Vuitton in 2018?

I knew there were three possibilities, that’s all I can tell you.

What came to mind straight away when you were offered the position?

I considered the offer. I don’t make plans, I do what I do, and that’s all. And it so happened that at that time I received quite a few different offers all at once. First and foremost, I wanted to think about my quality of life. I work a great deal, and I wanted to be sure that I could see more of the people who are important to me – and they’re all in London. I wanted to find the solution that best suited me, because it’s only then that you can give something your all. At Dior, nobody minds at all if I work from London. I come to Paris when necessary, and I do what I have to do – actually, to be precise, I do much more than I have to do. In any case, I work constantly.

How did you approach your first collection for Dior?

I had three ideas in mind: elegance, couture and cut. As for Dior, they wanted more colour and fun. We mustn’t forget that when Dior began, just after the Second World War, the aim was also to inject a bit of joy back into the world. I always try to imagine what would capture Christian Dior’s attention today, if he were still with us. I’m convinced, for example, that he’d be addicted to Instagram and would rely massively on new technologies and marketing tools. When he started out as a couturier, for example, he didn’t hesitate to use an American agent – and he was the only one to do that. He had a very progressive outlook. Malcolm McLaren, who absolutely worshipped Christian Dior, always saw him as the first ever punk. Which, as a Londoner, really speaks to me of course.

Speaking of Instagram, how on earth did you manage to reach 691,000 followers when I struggle to get six – including my poor mother and my intern?

No idea. At first, it was just an account aimed at my friends, and it stayed locked on “private” for a very long time. And then Vuitton asked me to remove the “private” parameter…

Was it difficult for you to transpose the historical codes of Dior’s women’s fashion – toile de Jouy fabric, the cannage motif, Dior grey and flower women – to menswear?

Absolutely not, because that was all created in the ‘40s and ‘50s and today, in 2020 or thereabouts, it’s exactly the kind of thing that men can wear. We’ve really made a lot of progress from that point of view.

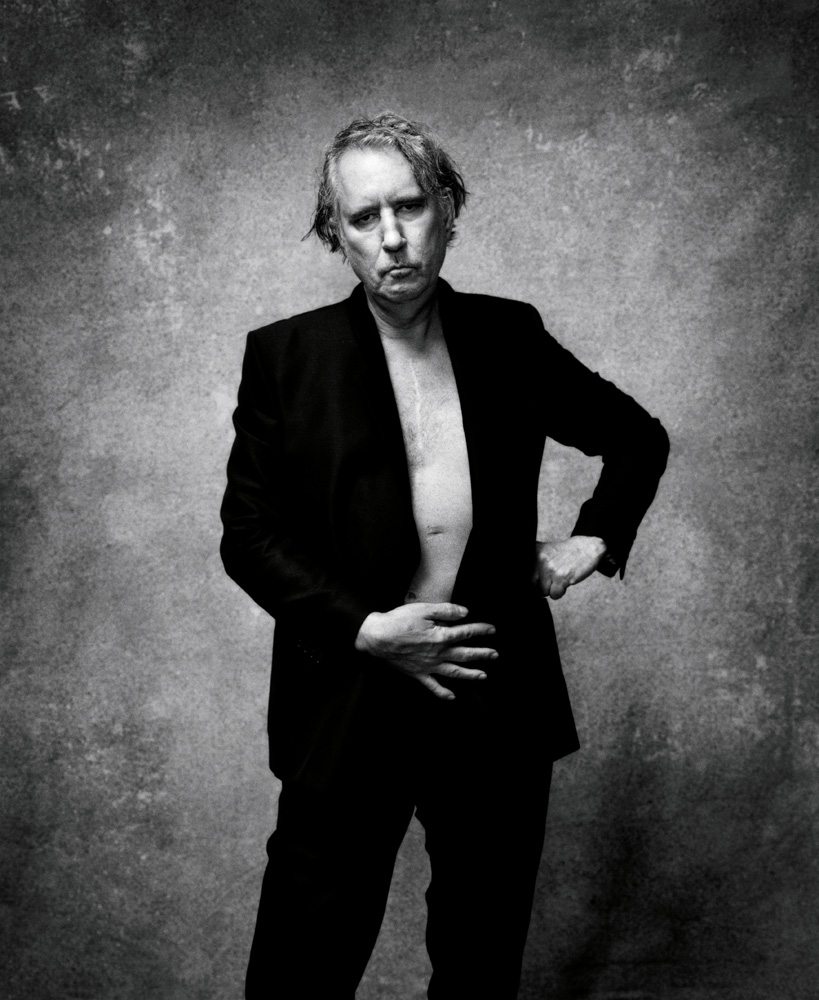

How and why did you choose Nikolai von Bismarck to photograph all those celebrities wearing Dior that we can see in your book, The Dior Sessions?

Nikolai, who is an old friend of mine, presented some of his work to me, and I really loved his very classic vision. I wanted the book to be a sort of timeless document that would embody Dior in 2020. It took a little over a year to gather all the participants together, and I really loved Nikolai’s way of working. I adore that guy, he’s like a brother to me.

How have you gone about casting those who appeared in the book?

They were either people that Nikolai and I knew, people with which Dior already had links, or people who had participated, in one way or another, in the Teenage Cancer Trust. All the proceeds from the book’s sales will go towards this British charity and everyone who agreed to feature has done so for free.

Can you tell us more about the charity you have chosen to donate to?

The Teenage Cancer Trust is a charity with which Nikolai and I are collaborating. It is dedicated to the fight against cancers affecting young people aged 13 to 24. The son of a friend contracted leukaemia. At the time, we all asked ourselves what we could do to help. Leukaemia can be treated if it’s diagnosed early, but if it’s left too long, it’s a real nightmare. Cancer is really the worst, because the means for curing it are still too limited.

In the book, the female gender is largely represented… Would you say that your clothes are designed to be worn alike by women or men?

With the exception of big ballgowns, I don’t see fashion as being destined specifically for one gender more than another. Tailoring constitutes an important part of what we do, and, let’s be honest, women always wear this type of men’s clothing. In this case, for the book, we targeted those we spend time with, our friends – independent of gender – and everyone wanted to be part of the project.

These friends, are they also your inspiration when you design a collection?

When I design a collection, I don’t think about me or those around me, I think of the client.

When did you realise you wanted to work in fashion?

At the age of 14, I collected magazines like i-D or The Face, and I wanted to belong to this world. I still didn’t know whether I wanted to be a photographer, graphic designer, artist or a fashion designer, but I nevertheless knew that I wanted to work in a creative career.

What was the trigger?

My friends and I were all crazy about fashion. We would flick through the pages of the magazines, saying, “Wow! That’s so cool!” We went to college during the day, then went out all night. That’s generally what young English people do. And it’s also how I came to meet Judy Blame, Lee [Alexander] McQueen, and other extraordinary people.

What memory do you have of the great Louise Wilson, taken much too soon, who was also our guiding light as director of the Masters in Fashion at the Central Saint Martins College?

Louise was one of my best friends, her death shook me to my core. The last time I saw her, I almost died laughing listening to her talk about the time she hit a student. For his end-of-studies project, this young man had spent his entire budget on creating these enormous life-size mannequins, but since the clothes had to be shown on catwalk models, these mannequins had been completely useless. Louise wasn’t happy, and, as you know, she could only see out of one eye. When the student presented his work on these infamous mannequins, she accidentally slapped him as she confused him with one of them. The story was so hilarious that Timmi, Louise’s partner, couldn’t stop laughing for three hours. This woman was absolutely priceless – you don’t get people like her anymore.

What is the biggest market for Dior’s men’s collections?

Traditionally, it was always China, but it’s increasingly spreading across the whole Asia-Pacific region, and Americas are growing very rapidly. On an international level, all big businesses want to balance their different markets so as not to depend on one particular area. At Dior, we managed to do that in less than a year.

How could I get my hands on one of the suitcases you recently designed for Rimowa?

Ask this man [he refers to Dior’s press and public relations manager]. For my part, I’m going to go and see Alexandre Arnault [Rimowa’s CEO] to ask him when I can have one!