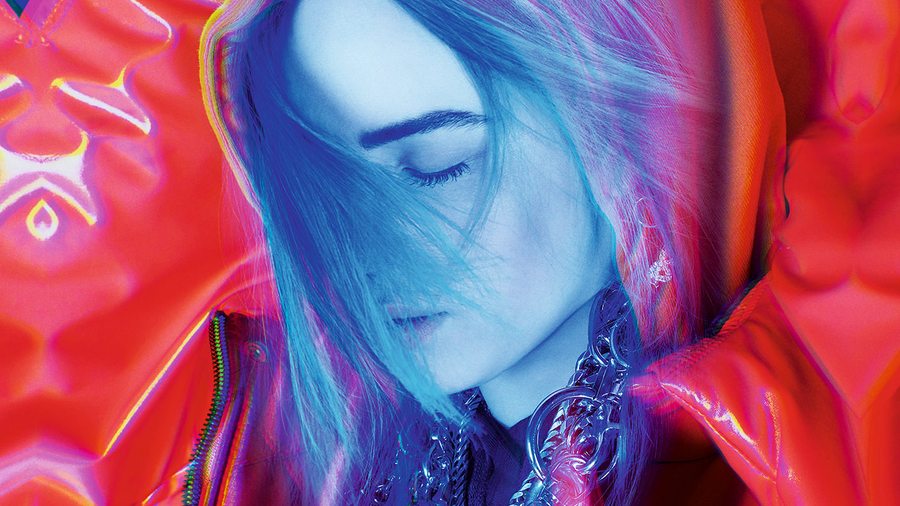

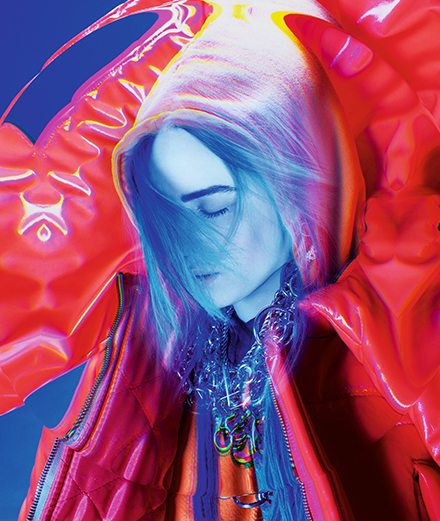

Billie Eilish is 17. Her hair is turquoise. Sometimes she wears a princess tiara. Live spiders crawl over it. There’s a chorus she likes to sing, “Quiet when I’m coming home and I’m on my own. I could lie, say I like it like that.” The standard melancholy and eccentricity of an American teenager, you might say. Except that she (de)constructed her adolescence under the watchful gaze of hundreds of millions of people, the Angeleno’s songs having garnered her 285 million views on YouTube (for her hit Lovely with Khalid). Shot in iPhone style, the video for You Should See Me in a Crown (the one with the big live spiders) has notched up 80 million views.

Billie Eilish has inspired Takashi Murakami a short film and a series of visuals.

The crystallization of a teenage icon is a fascinating phenomenon. At 14, Eilish had her first brush with success with her track Ocean Eyes. She could have become a precocious pop sensation à la Britney Spears, Justin Biba or Troye Sivan, but Eilish triggered something else. Fascinated by her, Stromae and his brother made the video for her track Hostage, and, for the release of her first album at the end of March, Takashi Murakami made a short film and a series of visuals. When we asked him to photograph her in Los Angeles, Tim Richardson came back with these incredible shots of her metamorphosing into a digital creature. Eilish is nothing if not inspiring.

Billie Eilish – “bury a friend (a film by Numero art)”

Billie Eilish is a mirror of our times, a moment in history when the reality of someone, of an artist, appears first and foremost through their presence on social networks.

She has a slightly disturbing and ghostly presence – half Exorcist-style possessed and half Stranger Things heroine. Indeed she’s reminiscent of another ghost: Ann Lee. In 1999, French artists Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huyghe bought the Ann Lee manga character from a Japanese company and used her for 3D videos and posters. Eilish, just like Ann Lee, is a mirror of our times, a moment in history when the reality of someone, of an artist, appears first and foremost through their presence on social networks. Ours is a society where all contact with reality is publicized, magnified and filtered by films and staged snapshots; all presence is, in a sense, ghostly. It’s also an era whose virtuality is marked by an exacerbated desire for emancipation. “I don’t want to follow in anyone’s footsteps,” Eilish told us, “and I don’t want anyone to follow in mine.” The more omnipresent the virtual, the more the ego must be materialized. Freed from the field of cultural industry, Ann Lee joined the artistic sphere just as Eilish today joins Murakami’s mangas and Richardson’s photos.

Many artists, from Amalia Ulman to Ben Elliot, have integrated the changing paradigms of the 21st century into their work. The truth of reality no longer opposes the fakeness of the virtual, the private sphere is no longer a protected domain (Eilish didn’t hesitate to post Instagram stories in response to a YouTube video about Tourette’s Syndrome, from which she herself suffers).

In one video, Eilish regurgitates a black liquid that adopts disturbing forms, vomiting her creativity via a digital creature, just as Elliot uses his “improved” selfies to show all the possibilities of his body and his characters.

In one video, Eilish regurgitates a black liquid that adopts disturbing forms, vomiting her creativity via a digital creature, just as Elliot uses his “improved” selfies to show all the possibilities of his body and his characters. Lots of artists use their body as a tool, staging the image of their body to make their art, the concretization of a possibility that was virtual. But with Billie and Ben it’s different, they virtualize the possibilities of reality, dematerializing their bodies and our world. And these post-humanist artists fascinate us.

When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? Album available.

Billie Eilish – “you should see me in a crown”