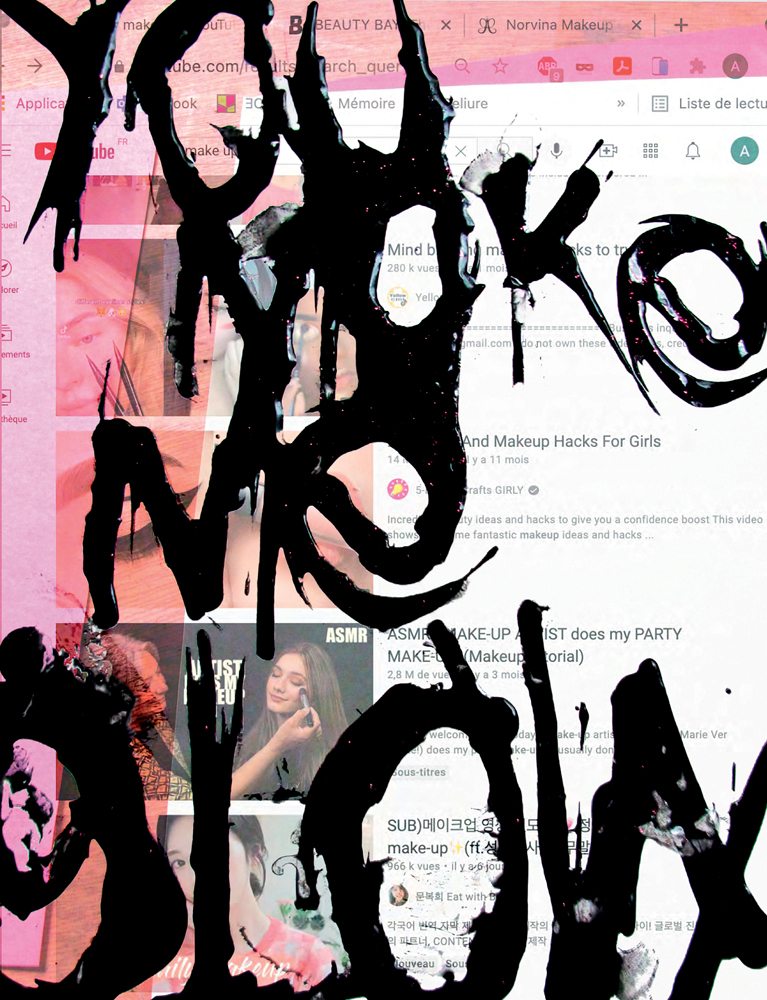

Aïda Bruyère adds volatile particles to a body in the making, fragments of words and images: “SHAKE YOUR BAM BAM” (COOL IT, 2019) or close-ups of buttocks (Mi Seh Bum Bum, 2019). Beams of light and swaying rhythms: Bamako nightclubs (Never Again, 2021) or twerking battles (Musoya, 2020). Sharp prostheses and ephemeral second skins: manicure tutorials (Nails, 2017-2019) and trashed make-up (Make Up Destroyerz, 2021). The body is absent, hidden behind its finery, which protects as much as it renders unreal, projecting it into a reinvention constructed through a meticulous ritual – a ritual in the sense that something remains to be conquered: an appearance, a temporary character, a collective identity. So everyone practices, polishes their moves, sharpens their claws and dons their face paint. When discussing her work, Aïda Bruyère often uses military vocabulary: dance, clothing and make-up, which she deploys in films, installations, performances and books, are all weapons in a “female war artillery” in an artistic practice that borrows from pop culture – its distribution networks, storytelling methods and attention-grabbing strategies.

At the 2019 Salon de Montrouge, where she was awarded the Grand Prix, 26-year-old Bruyère – who at the time was still a student at Paris’s École des Beaux-Arts – showed the installation United States of Gyalz. With its silk-screened prints of fragmented buttocks and contorted torsos, cadenced by litanies of syncopated onomatopoeia in bubble-gum typeface, it displaced the world of female dancehall into her exhibition stand, complete with items of dancewear casually strewn here and there and a video showing the SpecialGyal Universe meeting of a year earlier centred around Amazon-dancer Aya Level.

At 28, Bruyère is part of a “pop cosmopolitanism,” as Henry Jenkins termed it in his 2006 book on participatory culture Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers. He was the first to theorize the practices of everyday invention that consumers of cultural products engage in when they appropriate prefabricated content in order to subvert its standard uses: fan fiction, tutorials, mix-tapes and DIY are just some of the many ways to bring out alternative narratives within the black box of the cultural industries. With Bruyère, however, reappropriation happens within the prism of a very precise personal history that specifies her theoretical anchoring in an Afro-feminism and, more generally, an intersectional feminism. Born to Franco-Belgian parents in Dakar, Senegal, and raised in Bamako, Mali, Bruyère is intimately and personally aware of the dangers of the cultural hegemony conveyed by globalized soft power, which leads her instead to opt for realism and local remixes, sweat and dripping materials, observation and plural collaboration, testimonies and subjective archiving.

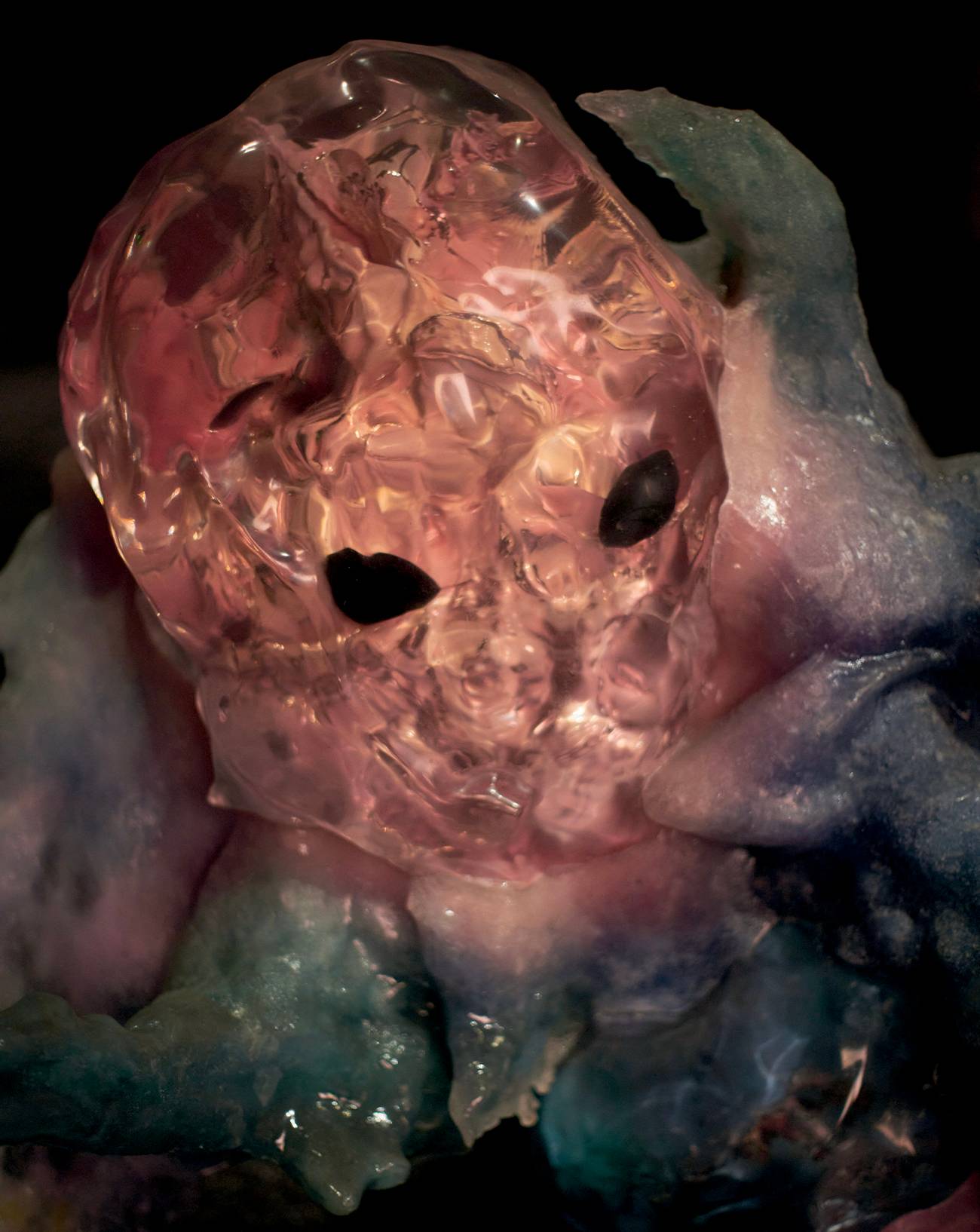

Because she knows she is caught in an in-between; because she is only too aware of having grown up white in a post-colonial country; because she maintains a genuine attachment to places that constitute her life rather than reappropriating them – so she adopts the most sensitive prism possible. While at the Beaux-Arts, in 2020, she created another immersive environment, dressed up in the colours of a nightclub and strewn with party wear and trashed make-up. It was conceived for the performance Musoya, co-written with booty-shake dancer Patricia Badin, who came on stage, her back to the crowd, to blindside the expectations of a non-initiated audience with respect to a universe addressed first and foremost to peers and allies rather than to the voracious and frontal consumption of the société du spectacle.

This is why Bruyère’s majestic warriors are never abstract creatures. They dissociate themselves from the aporias of a supposedly neutral cosmopolitanism that can just as much be found in the monoculture of the Internet: in reality, the cybernetic fantasies of a post-human era erasing gender and race only displace the inequalities of the real world, since “cybertypes” remain determined and defined by the ethnic stereotypes of today’s society – as American academic Lisa Nakamura demonstrated in her book Cybertypes (2002), the first part of an ongoing research project.

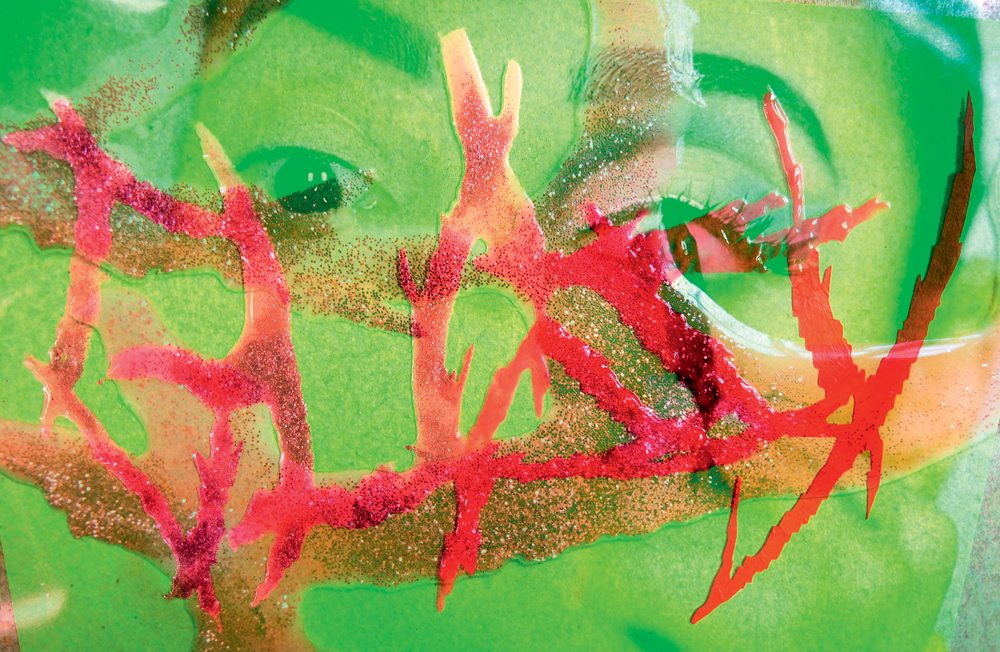

Bruyère’s exhibition Never Again, on display at the Palais de Tokyo this autumn and spring, will also be about a nightclub in waiting, inspired by the Bamako clubs that marked her adolescence, and more particularly the Ibiza Club. There, a safe and inclusive space took shape through clues, like the neon- or hacker-green fresco of a club that no longer exists, closed during the 2020 economic crisis in Mali which was worsened by the pandemic: Le Gurlz Blunt. To a soundtrack that combines fragments of music and personal accounts by Bruyère, who talks about her position in the art world and the cultural-industry ecosystem, something else emerges: a heterotopic takeover, shifting the destiny of these women warriors from the local to the global, from the intimate to the flux of mass media, where they will dance and shine forever more.