Numéro art: Can you describe your Venice show ?

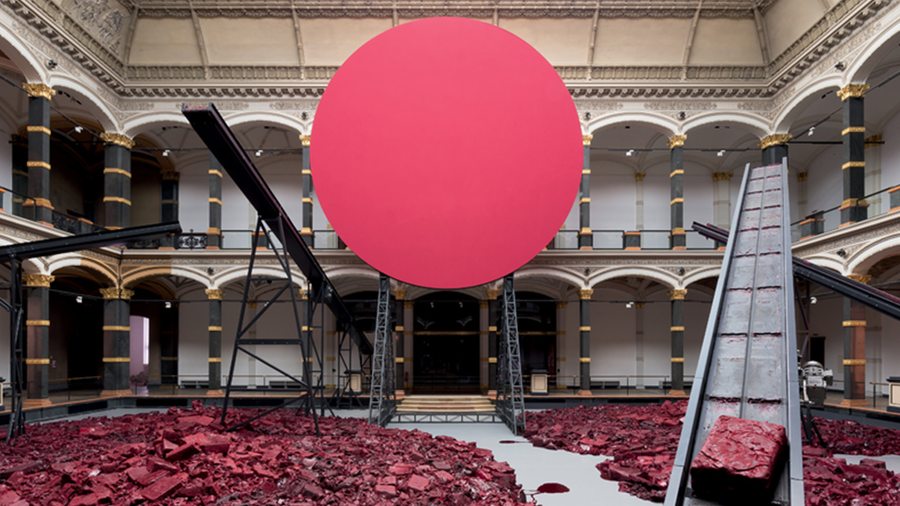

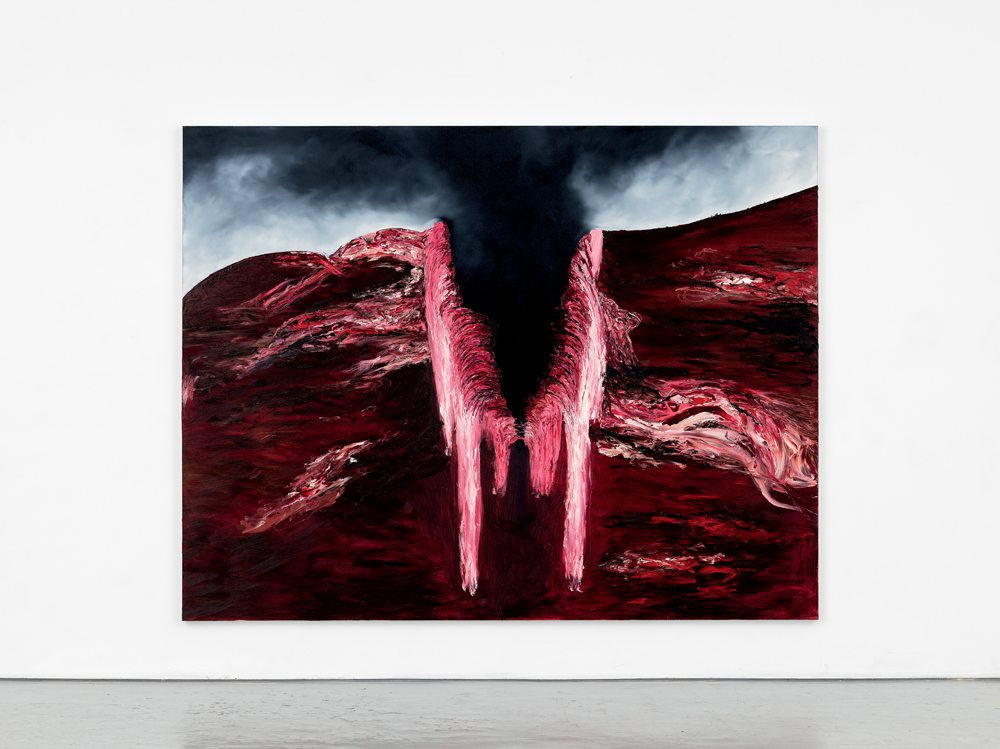

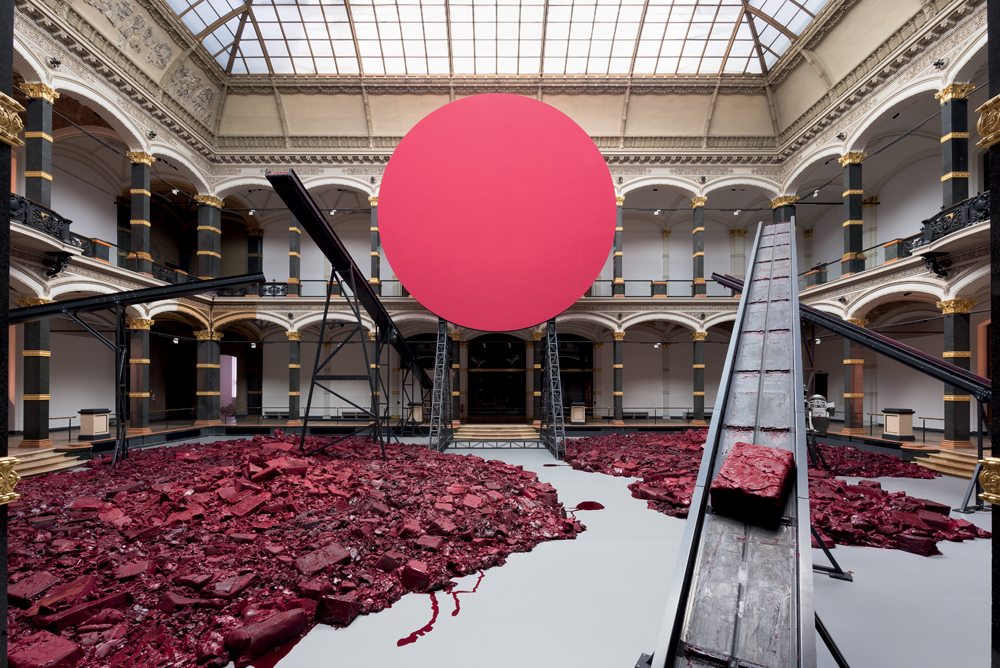

Anish Kapoor : It’s divided into two parts, one at the Gallerie dell’Accademia, the other at Palazzo Manfrin, which I recently acquired. At the Accademia you see a group of five or six paintings grouped around an enormous, bloody, visceral sculpture at the centre of the room, a place of sacrifice and ritual. The next room contains work from the 90s, very dark pieces, as well as Shooting Into the Corner [a huge cannon that fires balls of red wax onto the walls]. It’s a gigantic mess – I love it! The third room shows my new black works [Kapoor has developed a black so black that an object covered in it seems to become a gaping void], which play on the idea of present and absent, form and void, the object and the illusion of an object. I call them “non-objects.” The whole exhibition examines the idea of the physical presence of what’s inside, and of objects between two states – between the earth and the sky for example.

How does showing in Venice affect the works? Do they take on new meaning there ?

Definitely. I have a long history with Venice. There are two things. The first has to do with art history. Venice is a city of colour – its sky, its role as a bridge between East and West and with the Islamic world. The second is more mysterious. Venice is a city of water and darkness. But water is never just water in Venice. It’s maternal and deeply mysterious. What exactly is its power? What can it do? What is its depth? How far does it reach? There’s something unsettling about seeing all of these buildings rise from the water. The point where they emerge seems like a place where everything begins and everything ends. It’s some- thing that’s always struck me. Like Visconti, I see the beauty in it, as well as death standing just behind your shoulder. What’s more, showing at the Accademia obviously means rubbing shoulders with all the great Western art on display there, from Bellini to Giorgione, and con- fronting its themes. There are two great moments in the Italian Renaissance, the first of which is perspective. When perspective came along, human beings placed themselves at the centre of the world – suddenly everything is seen from a human perspective. The second is the fold, in cloth- ing and drapery, the way that great paintings play on fabric and clothing as signifiers of the human. The garment ex- presses the person and the body. But this black substance I’ve been using these past few years makes the fold dis- appear when applied to fabric. With this ultra-black, I’m seeking to go beyond the body, beyond the possibilities of form, beyond the being. In a certain way, it’s about taking Malevich’s black square even further by making a three-dimensional object into a four-dimensional one. The object “makes” something else. The idea is to question what is physical and what is transcendental. This is essentially what all artists do – it’s the principal and methodological goal of art.

It’s interesting you mention perspective, since your work often uses strategies of reversal, of evisceration. The top becomes the bottom, the interior the exterior, the earth is turned upside down...

The history of painting is the history of how things are made to appear. I’ve set out to do the exact opposite. How do you make things disappear? Obviously I’ve worked with various materials over the years. Black is one of them, before it there was blue pigment, as well as the white works, and of course mirror. Mirrors produce a strange effect, especially when they’re concave as in some of my pieces. Convex mirrors make everything seem small- er and reflect the entire room, whereas with a concave mirror everything’s upside down and the object’s space is no longer present. It’s no longer the traditional space of painting. You feel like you’re about to fall. What interests me here is the way in which phenomenological questions can become poetic or psychological questions. So I ask myself, “Wherein lies the meaning?” Is it in this moment of interaction between the viewer and the object, the view- er and the material? The viewer is always at the center, and some interactions with these objects can be violent and destabilizing. But for all that, is it simply a trompe-l’oeil? An illusion? On some level, yes. But what comes after the trompe l’oeil?

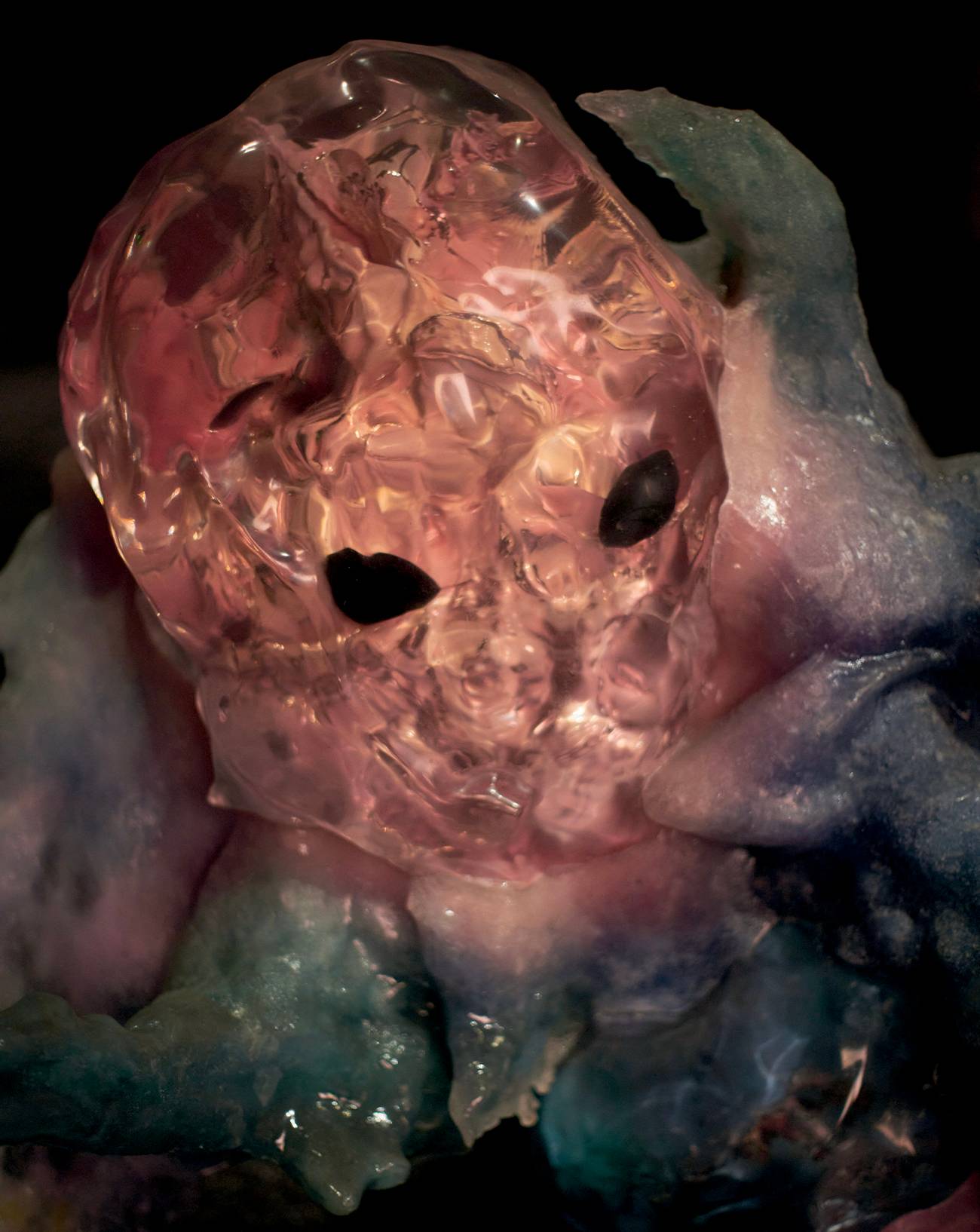

Some of your pieces show what we don’t want to see – the abject for example.

The idea of the abject immediately brings to mind Julia Kristeva [in her essay Pouvoirs de l’horreur – Essai sur l’abjection, the psychoanalyst argued that the mother and child are constituted in the early periods of the baby’s existence as “abjects”: neither subjects nor objects, but poles of attraction and rejection. The interaction of the “abjects” is made manifest in preverbal exchanges that she calls “semiotic,” impulses expressed sensorily by a pre-language articulated through intensities, rhythms and intonations]. Fundamentally, that leads us to think in terms of an inner language. Does our inner language allow for a “disruptive self”? We spend our lives negating this part of ourselves, and in turn we educate our children to forget it. We reject the difficult or the abject, we deny that which is not “good.” We don’t want to see it. But I believe this is a terrible mistake. Perhaps the artist’s role is to overturn that and say, “Well actually the Sex Pistols were right. Anarchy in the UK!” Our poetic self is to be found in the undisciplined and the deranged. Viewers come to an artwork with their own baggage of affects and emo- tions. They can look at it with love, hate, desire, whatever, and it’s up to the artist to play with that. And part of that is the abject.

There’s a lot of playfulness in this abjection though, in the way you articulate it in your work. The last time we spoke you told me you consider yourself a studio artist who likes to play with materials...

Absolutely. And that’s even more true today. If you’re a chef in a restaurant, you have to please your customers. Your food has to be good. What’s great about being an artist is that you don’t have to please them. You can make something absolutely disgusting and that’s fine. The visual language allows for the abject. And what is the abject? It’s the consciousness of death. A great work of art is always a remedy against death.

You talked about the “non-object” being shown in Venice. What does this mean?

It all started in my studio. I was working on my pigment pieces, and, without really knowing where the idea came from, I made a big ball, a sort of empty form. I hung it on a wall, then I painted it blue, but a very dark blue. And suddenly this shape became a non-form. It was no longer an object but a hole. But it wasn’t a hole because it was hang- ing on the wall! And so, over the course of several years and in very different ways, I worked on these “non-objects.” Many psychoanalysts have played with the idea of the ucanny, something that can’t be seen but is still familiar to us. Something hidden. The way objects function depends on our perception. Their methodological possibilities of being real or unreal depend on it. The “non-object” exists in a very conceptual plane: an object that does not become an object but a space. It’s exactly what happens with Malevich’s black squares. If you look at them, they seem very ordinary. And yet! What a remarkable feat to make a black square not only an object but a space.

Psychoanalysis helped develop a sceptical or suspicious view of the world, the idea that something else is going on behind apparent reality...

Really? I don’t think so. I see if differently. In medieval painting, before Luther, the religious object was always shamanic, or magical if you prefer. After Luther, the object became a text, something you must read. Today we’re looking to recover that shamanic object, this thing that says our psychic world is complex. And this is what psychoanalysis does. It points to the pre-Lutheran possibility of a magical world where things can be both one thing and another. You say you hate someone, but in reality you love that person. There is this constant reversal. The object is also the opposite of itself, the denial of itself. This is why, even if psychoanalysis claims to be a science, it is also poetic.

Like philosopher Marcel Gauchet, are you calling for a re-enchantment of the world after its “disenchantment”?

Yes!

What about Romanticism? Are you a Romantic artist?

Possibly. Why? If Romanticism is the idea that the human spirit can aspire to utopias, then yes. We live in a sad dystopian world. We’ve lost touch with the utopian part of ourselves, the part that says we are capable of a better, more egalitarian future. This is an aspiration we must pur- sue. In a way, we have to reconstruct a Romantic vision of the future. Is art the right place for that? I would say yes. Even if it acknowledges destruction and violence, it can also connect to the material and the non-material, to what is physical and what is ethereal. Classically Romantic!

I thought of Romanticism because of its relationship to the sublime, the idea of mankind up against Nature, more powerful than we are, violent and terrifying. Your work plays on that too.

The sublime is indeed important, this idea that beauty takes us out of ourselves, beyond ourselves, which immediately begets fear. Beauty and terror go together. What are we afraid of? Losing ourselves. And what is that, if not the terror of death? Deep within us, we are constantly wrangling with this question. Particularly at my age! [Laughs.]

Anish Kapoor at the Gallerie dell'Accademia and Palazzo Manfrin, Venice. Until October 9.