“We’re no longer shown pubic hair in public, that’s the biggest change,” explains Betty Tompkins when asked what she thinks has been the most dramatic change from when she started working, right at the end of the 1960s. The question was a general one, but with intent concentration she answered very precisely on the subject of erotic (or, to be frank, pornographic) imagery, a subject she knows well because it has been the subject of her painting, without notable exception, for the last 40 years. A choice that has cost her dearly. Aged 75, Betty Tompkins has observed the various changes, but also the invariables, that have marked the history of relations between the art of our times and the representation of sexuality. Complex relations that have even seen her pictures confiscated.

Contemporary art, which by its very nature is the place for all transgressions and provocations, shows a perplexing prudery with regard to the representation of sexuality. But then our very epoch is just as perplexing: while millions of pornographic images are freely available on the internet, Gustave Courbet’s 1886 painting L’Origine du monde, which shows the lower half of a woman with her legs spread and constitutes a major piece in the collections of the Musée d’Orsay, is ferociously censored by Facebook. Moreover, all the facts seem to suggest, given the way they keep their distance from the representation of sex, that what artists fear most is censorship, even though historically it never scared them and often even encouraged them to transgress. But that’s how it is these days: when it became “contemporary,” art abandoned scandalous representations in favour of replacement slogans; the word “penetration” on the wall of a gallery is far less shocking than a representation of the act itself. By becoming “contemporary,” art also redirected itself: towards museums, hunting for an ever increasing audience that cannot possibly be upset in a full-frontal way; and towards collectors, who are now very rarely genuine connoisseurs of art and avant-gardist transgression, but rather socialites looking for status symbols: when they throw dinner parties they don’t want to offend anyone with the canvas hanging in the dining room, which must be instantly recognisable, instantly acceptable and easily forgotten. Coffee anyone? The extraordinary paintings realized from 2006 by John Currin (one of the most expensive artists on the market whose works usually require years of patience to acquire), which depict extravagant sex scenes executed with the virtuosity of the great 18th-century French masters, were initially shunned by buyers aware that it would be difficult to hang such pieces at home. As for the museums, they might find a place for sexuality, as does so much current art, in the form of questions, claims, or protests, or in caricature and satire.

For that’s how it gets expressed in the art sold in the upper echelons of the international market, such as Paul McCarthy’s monumental sculptures involving a whole panoply of articulated mannequins or figures engaged in unexpected antics, like Train Mechanical (2003–09), a vast chocolate-coloured mechanized piece that features an automaton in the guise of George W. Bush taking a pig from behind. It should be noted that Jeff Koons (yes, him again) dealt a severe blow to the representation of sexuality at the end of the 1980s with his exhibition of photographs showing him frolicking with Ilona Anna staller, a porn star better known as Cicciolina, who for the occasion became his wife. Unused to shows of this order (the exhibition was announced like a film on a giant billboard) the art milieu, already distanced from the avant garde and its provocations, was initially outraged, and took its time to come round.

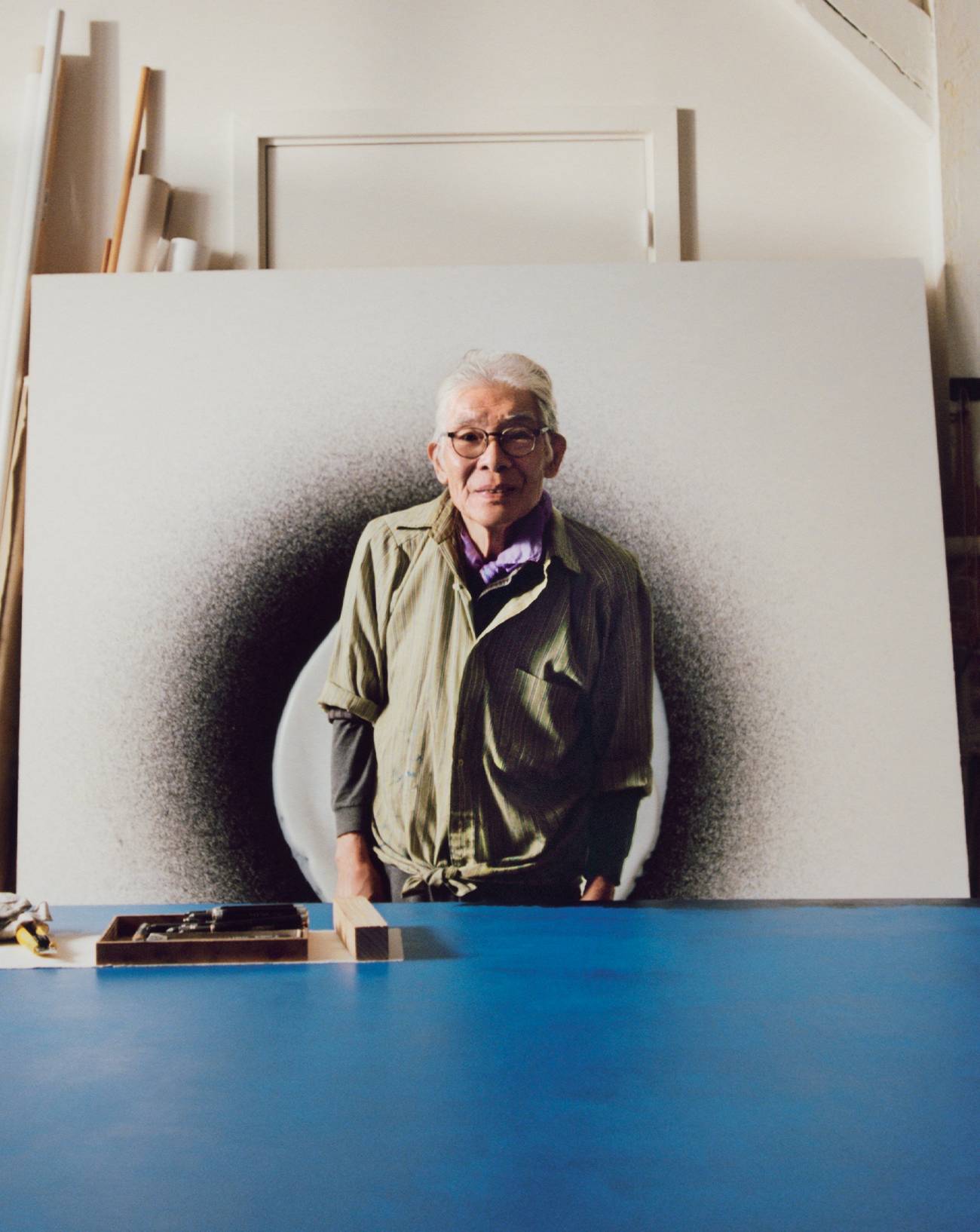

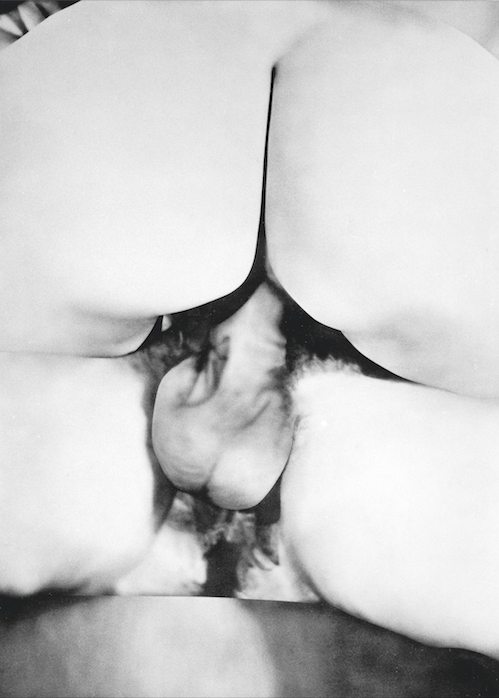

Betty Tompkins’s art is of a very different nature, still rooted in the avant-gardes of the era in which it was born. Tompkins studied painting – she had the same teacher, but at a different time, as the American painter Chuck Close – under the influence of Abstract Expressionism and Willem de Kooning. That was the starting point for her first figurative canvases conceived in 1969, the same year, as critic Robert Cicetti has pointed out, that

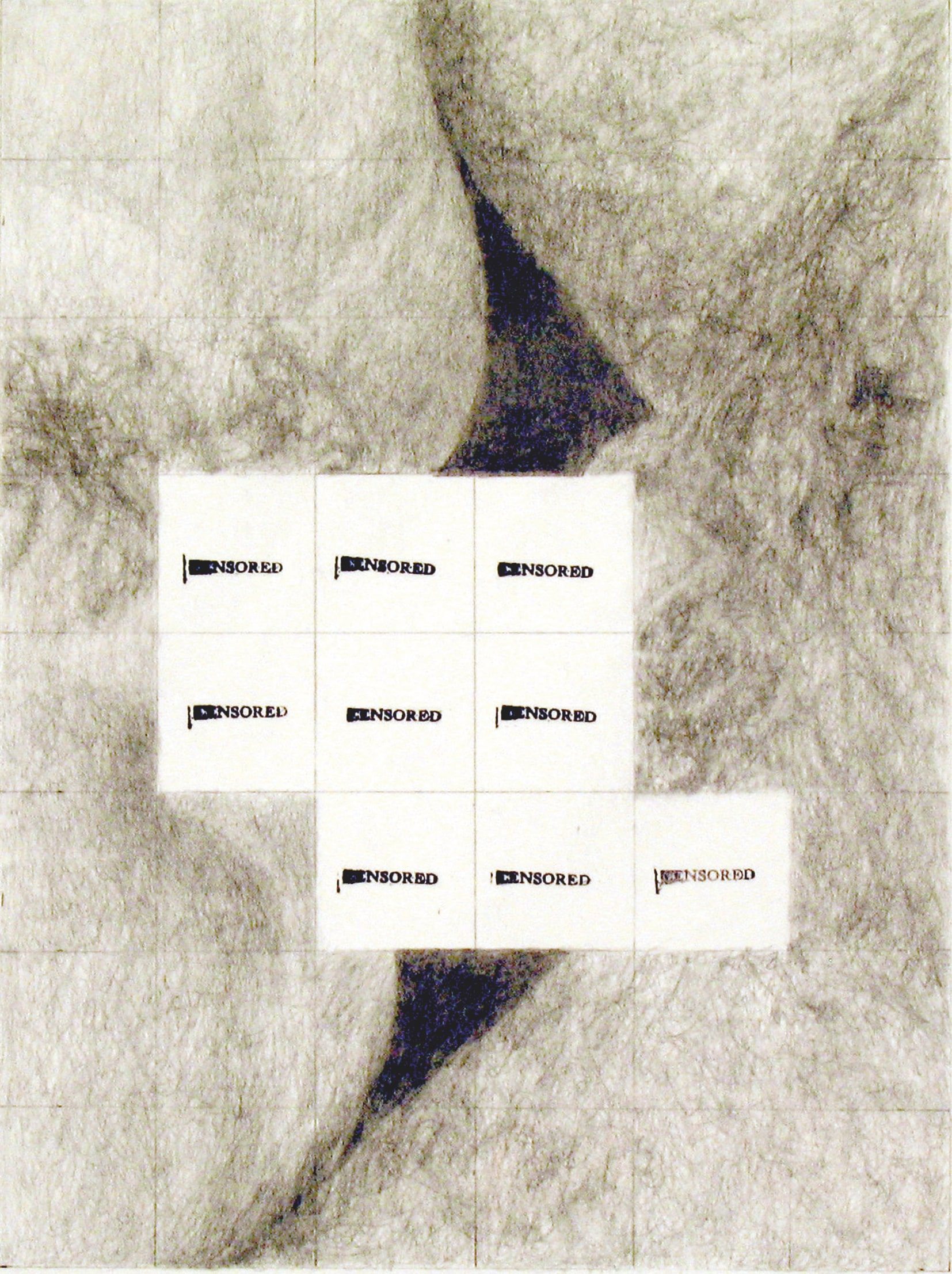

Neil Armstrong walked on the moon and that the possession of pornographic images was legalized in the U.s. The images that inspired Tompkins belonged to her then husband, who had acquired them long before she met him – he had bought them in Hong Kong and singapore and had them sent to him anonymously via a P.O. box in Vancouver. Cropped, reorganized and manipulated, they were recreated by Tompkins in black and white using a grid (never projections) and an airbrush on canvases as big as those of the Abstract Expressionists, their huge dimensions causing them to be haloed with a sort of sfumato. Composed in an almost encyclopaedic way, in close ups, without the appearance of a single face, the works could not be more explicit; they were what they were, presented with zero commentary, with no critical or discursive intent showing through the craftsmanship of the painting – just an instant form of celebration.

The art world had no idea what to make of them, and kept well away. “Most of the buyers I got in contact with refused to come to my studio. I never knew if it was because I was a young artist, a young female artist or if the problem lay with my subject, or if it was because a young female artist had dealt with this subject,” confides Tompkins. Eventually she managed to take part in a group show in New York in 1973 and, that same year, she was asked to show two of her paintings in France. But things didn’t work out as planned since the works were confiscated at customs, their entry onto French soil being flatly refused. And they remained sequestered for over a year. “It took me a year to get them back. At the time there was no internet or skype. An international call was extremely expensive and I didn’t have any money. I was really scared I would never get them home again, but finally they were repatriated. After that episode, apart from a few people who were enthusiastic about my work, I became a leper.” History repeated itself in 2005 when three of her drawings were held by customs before arriving in Tokyo for an exhibition there. In the meantime, Tompkins had lived through a long interval of enforced discretion which she views as a period with its own qualities: “seeing as I’ve spent the last 30 years outside the gallery system, I’ve been free to create without having to consider trends or the market. I was frustrated because I like exhibiting my work, but at the same time it’s been liberating.”

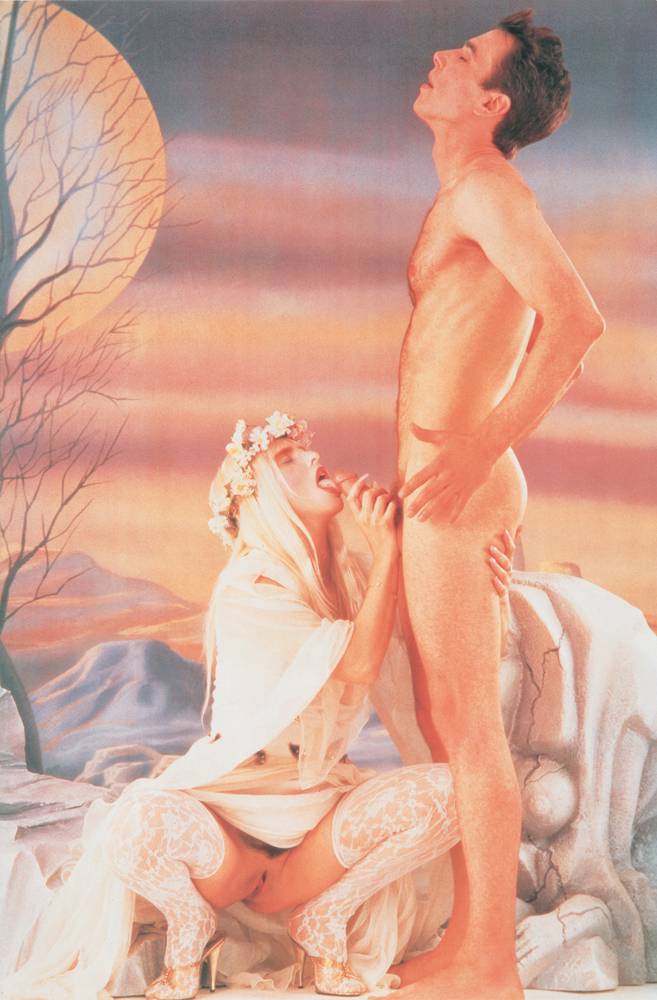

Jeff Koons, Wolfman (Close-Up), encre à l’huile sur toile recouverte d’un écran de soie (1991). Collection Astrup Fearnley, Oslo.

Jeff Koons, Blow Job-Ice, encre à l’huile sur toile recouverte d’un écran de soie (1991). Collection Astrup Fearnley, Oslo.

Things began to change at the turn of the millennium when gallery owner Mitchell Algus, famous for his pugnacious re-evaluations of the works of unjustly forgotten artists from the 1970s, got interested in her. The invitation I sent her in 2003, along with American art critic Bob Nickas, to show at the lyon Biennale had a redemptive effect, even though her paintings and those of steven Parrino had to be shown in a room controlled by a guard who refused access to minors and discouraged those with a sensitive disposition. The direct result of the lyon showing was the acquisition of a Tompkins canvas by the Centre Pompidou, which is currently the only museum in the world to own a piece of her work. “No American museum has ever exhibited, acquired or even accepted the donation of one of my pieces. And I don’t think the situation is likely to change soon. If it did change I would be very happy of course, but this doesn’t look like it’s going to happen,” Tompkins says. It’s heavily ironic that the work bought by the Centre Pompidou, Fuck Painting #1, was one of the pair that had got stuck at customs 30 years before. Tompkins decided to name her paintings in this way after revising the slightly silly concessions she had originally made to the trends of the time. “The original title of the Fuck Paintings was Joined Forms. It was like the heyday of conceptual art, you have to understand. You couldn’t read Artforum without a dictionary. And the Cow/Cunts paintings were originally called Condensed/Dispersed, which I now think is hysterically funny. I was too literal-minded and serious. It’s hard to have a sense of humour when nothing is going your way. I think it’s a hilarious title, but I do call them the Cow/Cunts. And the Fuck Paintings I never refer to as anything but the Fuck Paintings,” Tompkins explained to the art critic scott Indrisek in 2012. There’s no point trying to combine provocation and excuses, and Tompkins is not one of this new generation of artists who seek above all not to offend the market for fear of hindering its functioning. she is an artist, full stop, not a service contractor for an industry which now exists solely through its commercial activity.