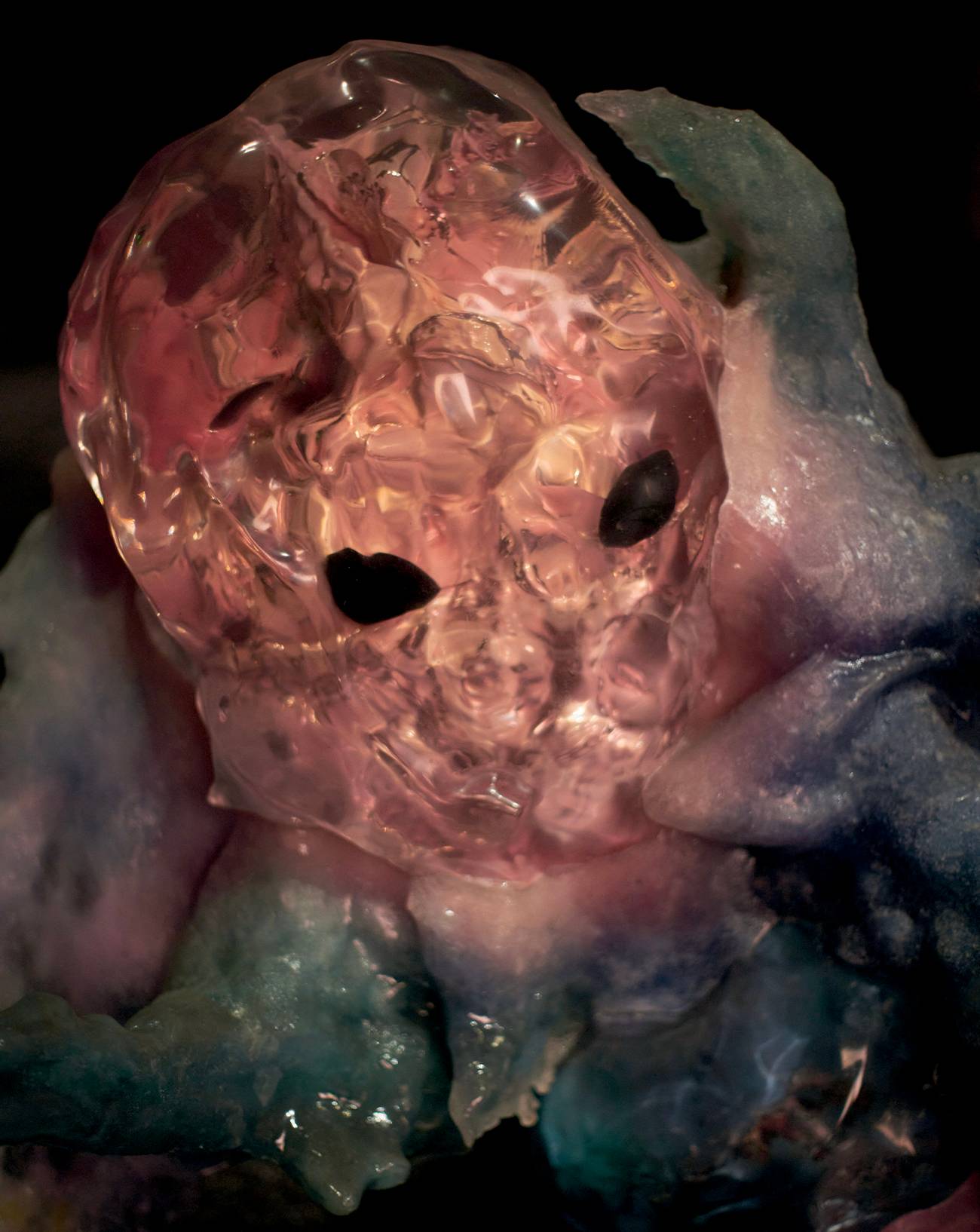

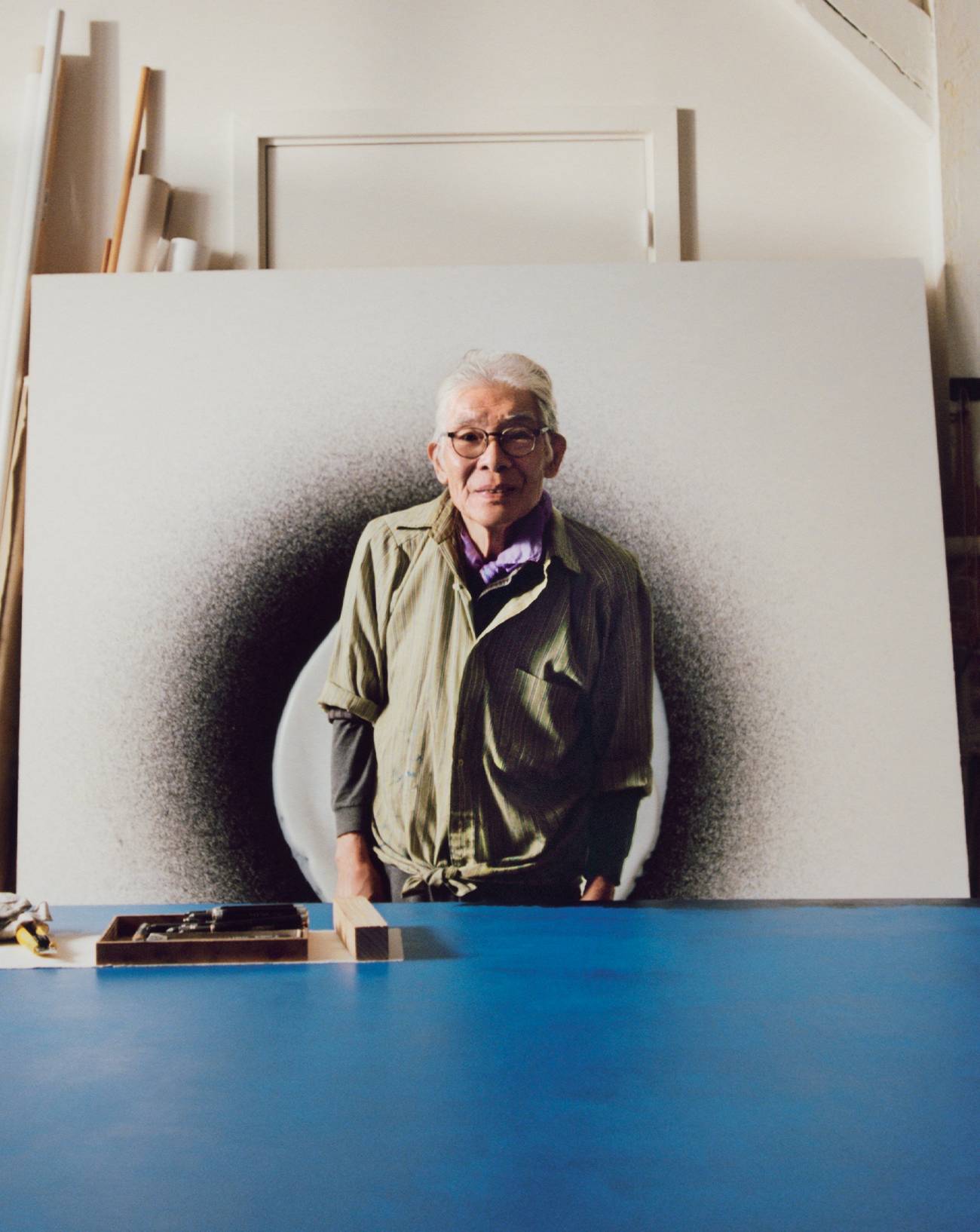

Takuro Kuwata is probably one of the most fascinating ceramicists on today’s Japanese art scene. Born in the early 1980s in Hiroshima, he initially studied the traditional techniques that are used to produce the bowls for the famous tea ceremony. But he soon began to perturb, subvert and go beyond the classic models to produce spectacular Artist of the month TAKURO KUWATA Part of a tradition stretching back millennia, the ceramic works produced by this Japanese artist captivate at first glance. Seemingly melted by ex treme heat, his mysterious and fascinating pieces open the doors to an oneiric world. Numéro talked to him about their origins and his creative process. Interview by Nicolas Trembley sculptures which, paradoxically, recall 3D images generated by algorithms. Kuwata makes his own pigments for his glazes, which combine several techniques of extreme complexity.

One such is kintsugi, an ancestral Japanese method for repairing broken porcelain using lacquer made with gold dust, while another, kairagi, involves superimposing several layers of white glazing. Or there’s shino, which has a more orange tone. Kuwata also lets chance have its say, experimenting with kiln times and temperatures, or using the ishihaze technique, whereby small stones left in the clay explode during firing, deforming his sculptures and giving them a bloated appearance. Like strange melted objects, his cups in incredible colours (silver, blue, red, etc.) are so fascinating that over the past few years they’ve become more and more collectible. Numéro caught up with him in Brussels, where he was preparing Good Morning, Tea Bowl, his second exhibition for Pierre Marie Giraud.

NUMÉRO: How did you become a ceramicist?

TAKURO KUWATA: As a child I already liked art, I liked to draw and paint. But I got into making ceramics later, at university. I undertook studies on three-dimensional objects, both sculptures and bowls. My classes were about the history of form and art history in general, but I didn’t go very often. I wasn’t a terribly serious student.

What was your first exposure to art?

TK : My parents were not at all part of an artistic milieu. Since they both worked, I was often alone. And I think it was that that made me creative. I grew up in the countryside, near Hiroshima, and I used to play alone in the fields near our house. As a child I really liked art class. I was in my own world and didn’t communicate that much with others. I liked the way I could express myself in those classes.

When did you decide you wanted to become an artist?

TK : When I was young I didn’t really think about becoming one. But I didn’t like studying and I did like art. And I thought a lot about death. I would ask my mother about it, about what happens to us afterwards. I wanted to leave a trace. I think that art is a way of confronting and going beyond death. And that’s probably what underlies my vocation.

What were your references in art?

TK : Initially I didn’t really have any. To be honest, I started by learning dance – hip-hop and street dance. I really got into it and got to know a lot of people in the dance world. I was also a DJ. When I went out clubbing, I used to talk to my friends, and that’s what influenced me most. Western culture too.

How did you get into ceramics?

TK : At the time when I was dancing I was at secondary school, but I knew I wouldn’t have a career in dance. When I got to university, I started taking lessons in ceramics. That was when I discovered the techniques and began thinking about becoming an artist.

What’s your positioning with respect to the great Japanese tradition of ceramics?

TK : At the beginning, traditional ceramics didn’t really attract me. It was through my university professors that I started to get interested in them. And the first pieces I made were themselves fairly traditional. I showed them to my dancer friends, but they weren’t terribly interested, precisely because they were so classical. So I said to myself that I needed to do something different that my friends would like and which would make them understand what ceramics are all about, their beauty. From there I developed a style that was influenced by things I liked from different periods: colour, silver and gold glazes, glazes that ooze or crack.

You exhibit your work at Salon 94, among others, a gallery that isn’t specialized in ceramics. Do you see yourself more as a ceramicist or a sculptor?

TK : I don’t really think I’m either, I consider myself more of a contemporary artist. When showing pieces at Salon 94 I have fun, I don’t work to a strategy. I like to exhibit my work in a place like this which also shows the work of other contemporary artists, because I find it very stimulating. Of course I was very influenced by traditional Japanese ceramicists such as Toyozo Arakawa, for example, but I don’t limit myself to ceramics, I go to see a lot of contemporary-art exhibitions. In fact I’m very inspired by contemporary creation in all its forms, from furniture all the way to music. I also try to find inspiration in the spaces where I show my work. Whether its Salon 94 or Pierre Marie Giraud’s, I like to check out the venue so as to think about the size of my pieces, to imagine what would work for people in that space. But that’s only one source of inspiration. When I create, I’m totally free.

“When I was young I thought a lot about death. I would ask my mother about it, about what happens to us afterwards. I wanted to leave a trace. I think that art is a way of confronting and going beyond death. And that’s probably what underlies my vocation.”

What were the ideas behind Good Morning, Tea Bowl, your second show at Pierre Marie Giraud’s?

TK : This time I wanted to work on the bowl, an essential object in the Japanese tea ceremony. I’ve been making tea bowls since the start of my career. Initially it was a Chinese tradition, but later Japan developed its own version, and the objects themselves became more abstract. I really wanted to put the object at the heart of this exhibition, and make bowls in a new style, revisit the tea bowl. Whence the title G ood Morning, Tea Bowl.

Do you create your glazes yourself?

TK : Yes. It’s very important for me, because when I make glazes I discover things that give me new ideas. For the simpler works, I have a basic glaze in which I mix colours. Today I know which glaze to use. Once I’ve got my recipe, I ask specialist firms to make it for me.

Your colours are incredible. How did you develop them?

TK : When making tea bowls, ceramicists are very precise. The amount of pigment used in a glaze is very carefully weighed in order to get a specific colour. When I started, I used colour any old how, without weighing it, and in the end I got a very flashy result. But it was all a bit of an accident.

Which pigments do you prefer?

TK : I like the metallic colours a lot. But since the place where I exhibit my work influences me, my choices vary according to the venue. For some I might choose a really pink pink, while for others it will be redder. It really depends.

How did you develop your “droplet” style?

TK : Initially I was planning to make a classic glaze, but when I applied it, it was too thick and started running. So I started making pieces with a few droplets, then I went on to make others where the effect was much more pronounced. Originally the colours were also lighter, but over time I made them more flashy.

Some of your pieces seem more like sculptures. How did that vein in your work come about?

TK : When I started exhibiting in contemporary-art galleries, I began to develop, from the basis of a tea bowl, things that had no use, that were purely decorative.

You also make large-scale sculptures. How did those begin?

TK : Since I was exhibiting in bigger venues, it seem natural to make bigger pieces. Certain contemporary-art sculptures also encouraged me to change format. But the tea bowl is always my point of departure, and my big pieces still have something of the tea bowl in them.

What would you like to get across to your audience?

TK : I consider myself a very free artist, and I’d like people to think of me that way. I make utilitarian objects, a cup or a tea bowl for example, as well as others that are pure sculpture. I constantly go from one to the other. It’s really in that particular space that I develop new things.

Does anyone use your bowls?

TK : Yes. Sometimes I make work that isn’t supposed to be used but in the end is. Meeting people inspires me too. They help me imagine new things.

Do you work alone or do you have a studio with assistants?

TK : I worked alone for a very long time. But since I’ve been making bigger pieces, I’ve needed help. I design the form, then it’s my assistants who paint it. I have a kiln in my workshop where I fire my own pieces.

Are the big works fired in one piece?

TK : The biggest piece I made was 3 m high. It was made in two parts, one that was 2 m high, the other 1 m high, which I fired separately before putting them together.

Do you have surprises in the kiln, or have you totally mastered your technique?

TK : I calculate the result before firing the piece, but never 100%. I let chance have its say, and it always produces something interesting.

What are your new projects?

TK : From kitchen tiles to the bathtub, ceramics are very present in our lives. I’d like to experiment with that, get involved with an architecture project, create furniture and things for the home. I’m also working on an exhibition in Tokyo this September.