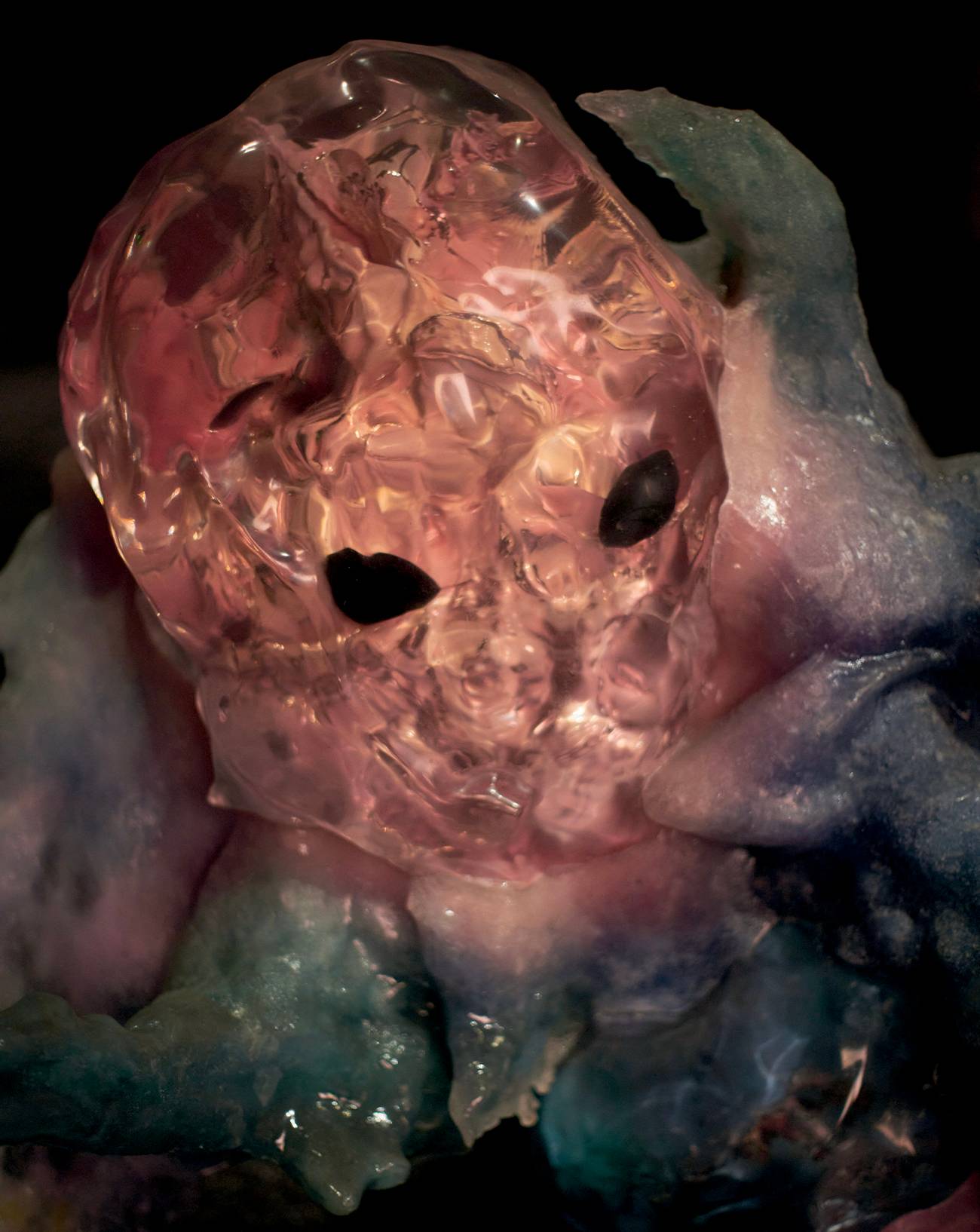

Through his sculptures and installations, 33-year-old French artist Kim Farkas, who is of Peranakan and American descent, develops a speculative materiology from contrary polarities: out of their zones of friction and points of con- tact, form emerges. Among his pieces is an oblong envelope that evolves, grows and develops, adorned with the liquid reflections of a toxic preciousness. Barely petrified, as if animated by muffled palpitations, it swallows and digests various found objects taken from the real-world economy of goods and merchandise that are then reinjected into the symbolic economy of Farkas’s oeuvre. More specifically, these opposing polarities concern the multiple ways in which time-honoured beliefs meet post-Fordist globalization.

In his more recent work, the surface effects, which result from a reappropriation of DIY techniques – from tuning to hacking – are partially reterritorialized though contact with commemorative objects produced for export to Asian communities abroad (reiki pieces or votive papers), while the post-natural organicity of pieces resembling epiphytic organs or digestive ducts is achieved through a gradual purification of his referential apparatus, as Farkas moves away from representation to presentation.

While studying at Paris’s École des Beaux-Arts, Farkas began moulding heads in polished resin that bore a resemblance to the augmented, or at least altered, humanity of science fiction: alien heads, which would later become empty shells. These then mutated into ducts, tubes and abdomen – the oblong pouches that constitue his current work – which retain a resonance with the body. Though at first glance this body no longer has anything human about it, that doesn’t mean it is fictional: through radicalization and exacerbation, it reflects the contemporary porosity of a body that is, from the outset, traversed by the non-human flows that inform it in return. In his 2015 essay Tentacles Longer Than Night – the final part of a trilogy on “the horror of phi- losophy” – Eugene Thacker invoked the “tentacle” as a figure of thought to signify the meaning of a contemporary world that has gone beyond the Modernist opposition between inside and outside, in the same way as Junji Ito’s Uzumaki manga series (1998–99). Ito imagined a city that gradually transforms into a spiral: the shape begins to inform all its constituent parts, from blades of grass to houses, until it devours the inhabitants, who become demented and succumb to murderous madness. As Ito recounts, “The madness of the city’s inhabitants is inspired by a duplicity: the tangible presence of the spiral combined with its intangible abstraction.” Farkas’s tubular envelopes have a similar relationship to figuration, while emphasizing the more directly socialized phenomenon of “creolization,” as he refers to it. Complex and resistant, fluid and iridescent, his forms materialize diasporic individuals composed of layers of memory, geography and economic flows, summoned to constitute themselves as entities in the very absence of totality.

![Kim Farkas, 21-24 (Detail) [2021]. Composites boxes, Loud-speaker and sound and video amplifier (11 min, 58s).](https://numero.twic.pics/2022-01/kim-farkas-portrait-numero-magazine-3.jpg?twic=v1/quality=83/truecolor=true/output=jpeg)

![Kim Farkas, 21-24 (Detail) [2021]. Composites boxes, Loud-speaker and sound and video amplifier (11 min, 58s).](image:https://prod1.numero.com/sites/default/files/2022-01/kim-farkas-portrait-numero-magazine-3.jpg)