Jean-Pierre Criqui: Your exhibition at the Centre Pompidou is titled Le grand atlas de la désorientation, chapitre 2. In mythology, Atlas carried the heavens on his shoulders. The word also describes a collection of maps...

Tatiana Trouvé: I don’t carry the world on my shoulders, let me assure you. [Laughs.] I’m referring more to maps and, of course, large atlases, whose ability to contain huge amounts of knowledge about the world has always fascinated me. The idea of “disorientation” is also essential as I see it. Art practice is a place of disorientation, where doubt plays a driving role. Had I been certain all throughout my career, I think I’d have only made one piece. But what interests me most about disorientation is that it allows us to perceive anew. If you get lost on a walk and are disoriented, you immediately become more attentive to what’s around you. Things reveal themselves differently. Perception requires a form of concentration and disorientation.

The exhibition is titled “chapitre 2” because a first chapter, in a smaller format, preceded it. Are you writing your great atlas of disorientation chapter by chapter?

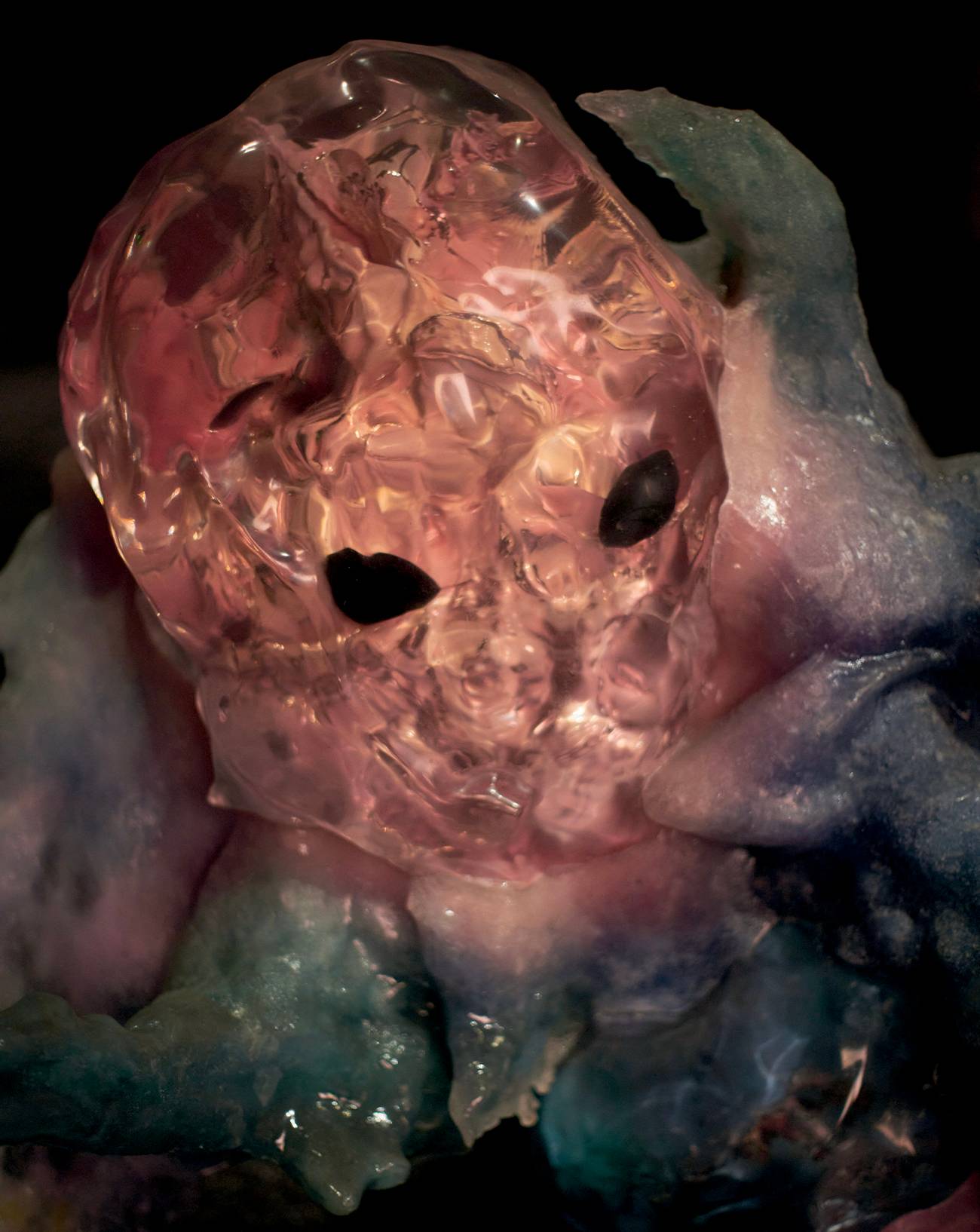

No, but I like stories and narratives. I think my work in general and my sculptures in particular contain stories within them. The idea of “chapters” reflects movement, something that carries on and that evolves. My atlas is an atlas of movement, of things that are unfixed and that can’t really be represented.

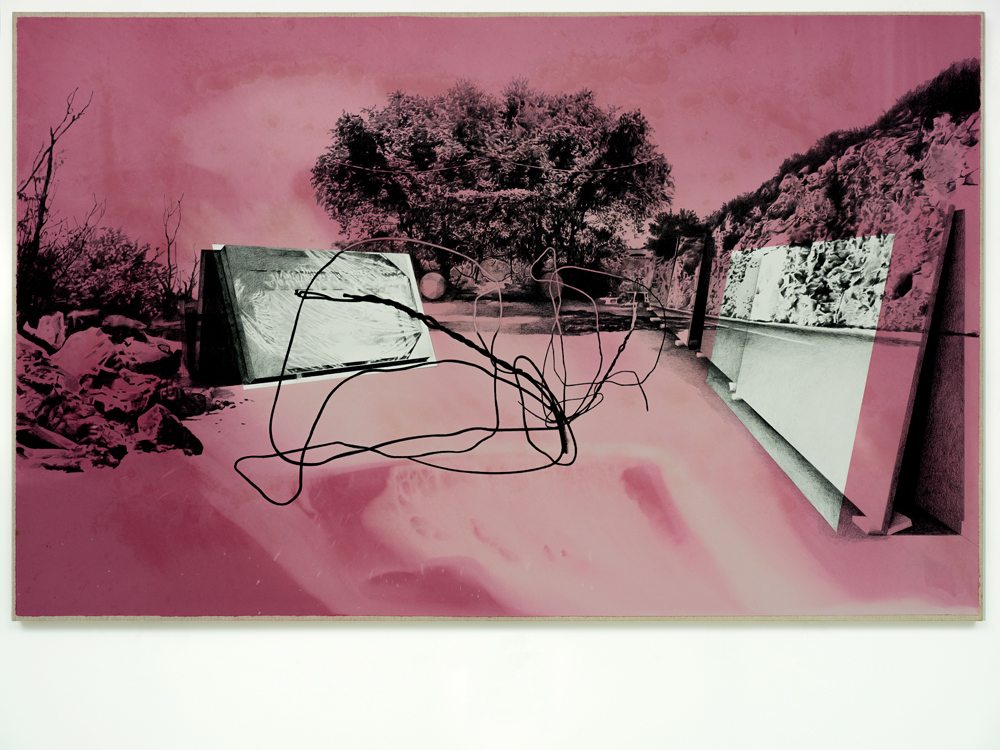

The exhibition includes drawings and sculptures, but also a very distinctive treatment of the gallery space. You’ve installed large curtains and monumental furniture, and the floor is covered with a large drawing, like a chaotic map that transforms the entire space.

Yes. I tried to recreate a path for the eye, where things circulate and come together constantly. This type of disorientation allows visitors to connect the drawings and the installations. There are also bench-sculptures, hybrid pieces that form the link with everything else in the installation. The hang allows the eye to travel: it’s a very physical journey, that of the body, a journey in a space, because you walk under works, sit among them, and walk on drawings...

So we’re in a Lucio Fontana-style “ambiente,” with a strong interior-design aspect to it.

My father was a professor at the school of architecture in Dakar, but he was really more of a sculptor to be honest. In fact, I was far more influenced by radical architects like Ugo La Pietra. I’ve never forgotten one of La Pietra’s aphorisms: “To dwell is to be at home everywhere.” For me, it’s not so much a question of being interested in homes and interiors and more of being interested in an experience where the outside world is constantly intertwined with an inner world. For instance, when, in his novel Walden, Henry David Thoreau describes a scene where the narrator takes all the furniture out of the cabin he lives in and realizes the furniture is better outside in the forest. There, interior and exterior worlds intertwine. I like architecture when it goes against the dwelling, when what’s external can also become someone’s interior world – a world where they can live freely. Something that’s crossed by flows.

You also recently spoke to me about planets, about the collision of planets, and about the movement of heavenly bodies in general.

I was essentially talking about diagrams that represent things that are in motion, and about the dream patterns of Aboriginals. For them, dreams are very important – they define their relationship to the world. Their perception and practice of dreaming are very different from those in Western societies. For Aboriginals, dreams don’t come from the unconscious, which is something detached from our way of being. Dreams for them have a collective reality, they determine the organization of the day and the journeys that are made. In fact, I’m interested in any diagram that attempts to represent things that, without being fixed, are extremely important and structure both knowledge and societies. The drawings and diagrams I’m going to do on the floors of my exhibition will incorporate these bodies of knowledge, which become formalized when they are drawn but are then constantly transformed – they will be redrawn and erased by the footsteps of all the people who come to see the exhibition. So, when doing the drawing, I’m fixing something at a particular point, something that actually can’t be fixed and will be reconfigured by the flows of visitors.

In his book The Songlines, Bruce Chatwin refers to Aboriginal “songlines,” which are networks of consciousness and paths along which they travel and dream. There’s a lack of distinction between dream and reality in the Aboriginal world – we never really know if we’re dreaming or being dreamed by someone else.

Exactly. The world was created by dream beings who gave it shape and form. The world was dreamed up and, therefore, to dream is to inhabit the world. This complementarity of dream and reality interests me. What’s more, if you look closely at my drawings, you’ll see that they include these kinds of interiors, these sorts of human presences, but you can’t tell what they really are because they aren’t representations or portraits. When it comes down to it, I think human presences are everywhere in my work.

Yes, but indicated by their absence.

There are many worlds present in my work, like, for example, the world of plants. I’m very interested in biological phenomena. Intelligence can be defined as a certain ability to understand and react to things that happen. When we humans are faced with danger, we run, whereas plants can’t do that. They can’t move so must find a way to defend themselves, for example by producing toxins or communicating with other plants around them so that they call on insects to come and attack the aggressor.

In the exhibition you’ll also be showing your Gardiens, a series of sculptures in which you make representations of chairs on which are placed various objects suggesting the presence of someone who is not shown or is absent. A Gardien with no guardian, in fact.

They’re a bit like Alberto Caeiro’s The Keeper of Sheep in Fernando Pessoa’s writings. They allow us to think about the world – to shepherd a changing world and to reflect on it. There’s also The Guardian newspaper, which bears that title because its editors believe there are values to defend: a democracy without independent sources of information is nothing. Symbolically, The Guardian wants to be the guarantor of this idea. My Gardiens were made to be part of a community and were designed to coexist with other works, but also to indicate a gaze.

And guards also make us think of museums of course.

Yes, they’re wardens of knowledge.

Could you talk a little about your series Les Dessouvenus [a term that translates literally as “those who have deremembered”]? Where does that word come from?

It’s used for people with Alzheimer’s who’ve lost their memory. It’s part of everyday speech in Brittany. I was struck by the great beauty and delicacy of the word – it evokes the idea of unfolding in reverse, as if it were something one did from the inside and not something external that happened to you. The use of the word also symbolizes a way of being together: being with a “dessouvenu” isn’t just being with someone who’s unwell and needs to be be put in a hospital, it’s also another way of perceiving others, of weaving connections, of creating one’s world. I’m sensitive to language because it speaks of our relationship to the world. I think calling someone a “dessouvenu” and not just an “Alzheimer’s sufferer” changes the relationships we can share together in a common world. In fact, what interests me more generally is how we humans perceive things, and also how others – how non-humans – might perceive them, and how that connects us. Maybe I see a tree as something that bears fruit, or as a supply of wood that I’ll chop up to make a fire. But maybe a bird perceives it as a place to land, or as a dwelling, a solid branch on which to build its nest. And a tree is neither one nor the other, it’s all of that at once.

Exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, from June 8 to August 22. Exhibition at the Gagosian gallery, 9 rue Castiglione, Paris, from June 8 to September 3.